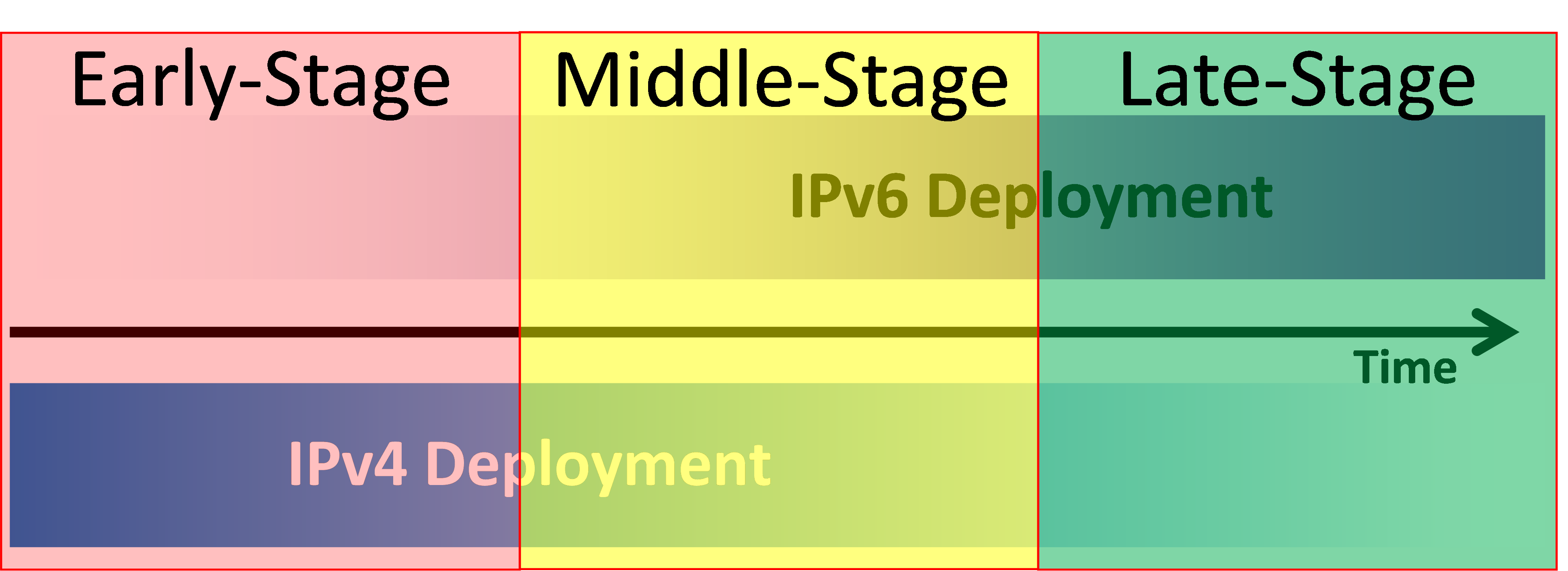

The enterprise journey from using solely IPv4 to running IPv6-only leads through different stages. It will take many years for enterprises to phase in IPv6 as they begin to phase out IPv4. The early-stage transition techniques involved joining islands of IPv6 over an ocean of IPv4. The middle-stage transition involves both protocols in parallel in a dual-stack configuration. The late-stage transition techniques are still developing as organizations are seeking to operate a single-protocol, IPv6-only environment.

Back in 2007, the typical guidance on IPv6 deployment was “IPv6: Dual stack where you can; tunnel where you must“. In the early days of IPv6 deployment there were many tunnel-based approaches intended to smoothly allow implementors to roll out IPv6 on top of an existing IPv4 network. However, there were downsides to techniques like 6to4 (RFC 7526), ISATAP (RFC 5214), and Teredo (RFC 4380). Tunneling techniques added overhead, reduced MTU size, and required latency-adding backhauling through a gateway. There were also many security concerns about IPv6 during this early period. These issues led to IETF discussions of deprecating dynamic tunneling approaches. Steps were taken to demote them in the address selection preference policy tables (RFC 6724 section 2.1) in host operating systems. That is why the IPv6 prefixes 2002::/16, 2001::/32 have low precedence values. Now, Windows 10 and Windows Server 2019 have ISATAP (since the Creators Update – 1703) and 6to4 (since the Anniversary Update – 1607) disabled by default.

During the middle-stage of the transition, the predominant Enterprise IPv6 Deployment Guidance (RFC 7381) has been to deploy IPv6 to create a dual-protocol network. Even today, some enterprises are struggling to start their IPv6 journey and are postponing their dual-protocol deployments. It appears that some enterprises are “playing chicken” with the oncoming rapidly-approaching IPv6 requirement and are delaying deployment. They are in danger of becoming in the “technology laggards” category when it comes to IPv6. They could be delaying for a variety of reasons, such as lack of talent or skills with IPv6, being unable to articulate the business benefits, financial or operational reasons to adopt IPv6, or other non-technical delays. We previously covered some common “issues” that enterprises come up with in the “IPv6: It’s Not You, It’s Me” post.

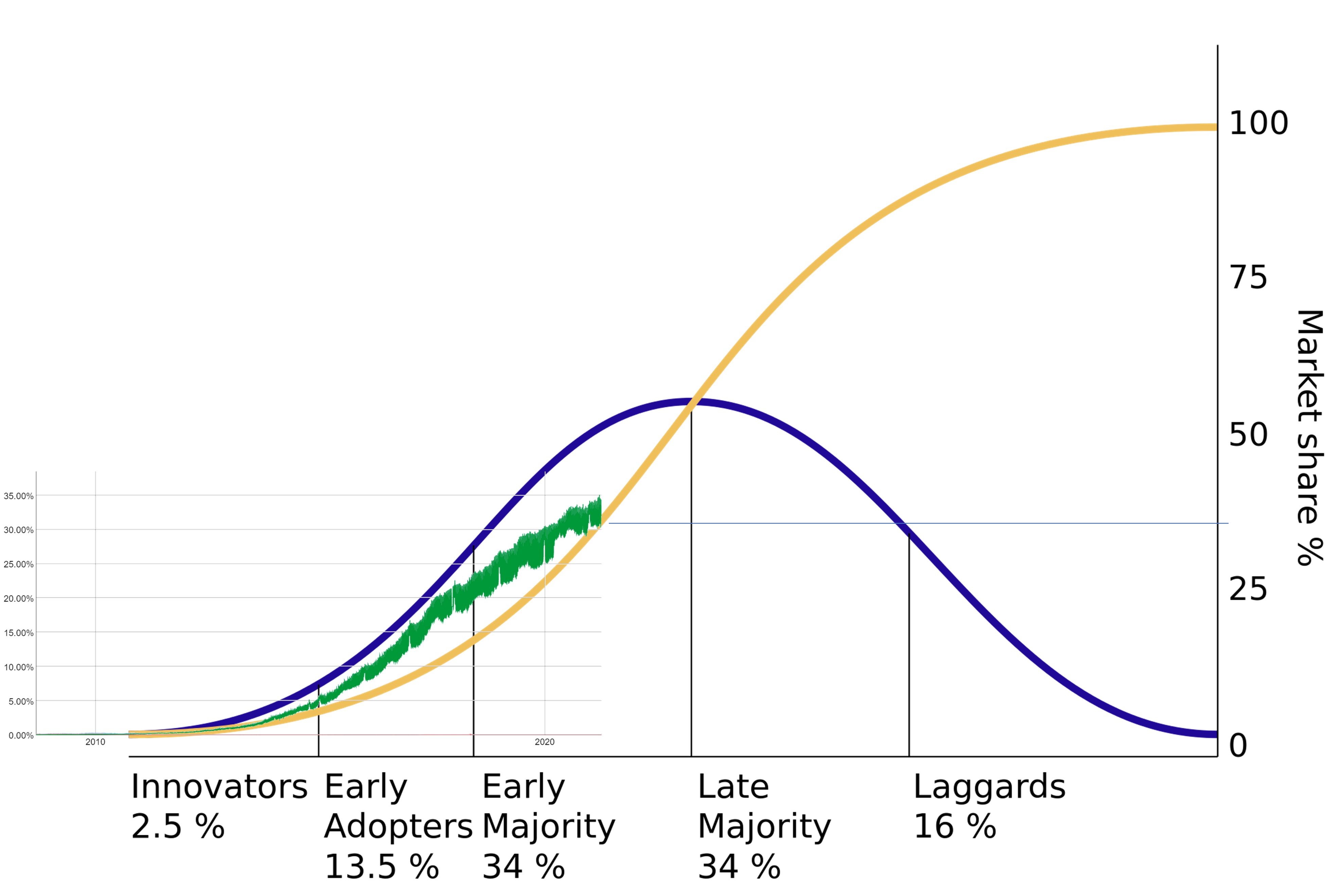

There is evidence that IPv6 usage on the Internet has been growing slowly but significantly over the past decade. The graph below shows the typical “diffusion of innovations” graph with the Google IPv6 Statistics graph showing the actual IPv6 usage. This green-line graph is the global IPv6 usage from Google’s content-provider perspective as an early-adopter of IPv6. (Side-note: On the Google IPv6 Statistics graph, the weekly oscillation of the green line is “enterprise effect” whereby end-users consuming Google’s content are more likely to go over IPv6 when at home or on their mobile device, than when they are inside the IPv4-only office.

Ice hockey star Wayne Gretzky’s famous quote “I skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been.” also applies to the enterprise transition to IPv6. By the time enterprises get around to deploying IPv6, it will be the dominant Internet protocol. If an enterprise observes that IPv6 usage in their country of operation is between 40% and 50% today, and it expects them to take 4 years to fully deploy IPv6, when they finally get IPv6 implemented the country’s IPv6 usage could be at 60% to 70%. This late-mover strategy may place a traditionally innovative and technology aggressive company into the unenviable “slowpoke” category.

When the IETF protocol designers were creating IPv6 and planning for the transition to this new protocol they did not intend for organizations to spend a lengthy amount of time in the dual-stack middle stage. Unfortunately, there are still many IPv4 dependencies in enterprise networks and most enterprises still need to operate an IPv4 environment (including NATs). There are some significant drawbacks to spending too much time in the dual-stack phase and one of the primary considerations is the increased operational costs to maintain a dual-stack network and all its connected systems and applications running on two protocols.

Fast-forward to today and much of the Internet, wireless mobile services, and residential broadband subscribers are actively using IPv4 and IPv6. When running dual-protocols, algorithms like Happy Eyeballs (RFC 8305) attempt connections using either IPv4 or IPv6 depending on which one performs best. However, this “behind-the-scenes” optimization can make it difficult to troubleshoot when either of the address families fail. Dual-stack can mask IPv6 failures, giving enterprises a false sense of security that their IPv6 deployment is solid. End users may not realize they have broken IPv6 connectivity until they reach the point of starting to remove IPv4 from the environment (and remove Happy Eyeballs from the equation).

Therefore, one of the benefits of running an IPv6-only network is the simplicity of operating an environment with a single protocol with a simpler address model. IPv6’s plentiful supply of globally-unique addresses relieves organizations from the constraints of limited public and private IPv4 address space (and can even help solve challenging technical problems arising from business growth such as mergers and acquisitions). Moving toward IPv6-only is the best and only way to completely divest one’s self of the constraints of IPv4 (like NAT and limited RFC 1918 space) and potentially obtain the performance improvements of IPv6.

Now there are organizations that are contemplating or have already moved into the late-stage of IPv6-only networking. Tech-forward companies like Microsoft, LinkedIn, Facebook, Cisco, Apple, T-Mobile, and Google have had IPv6-only environments for many years. Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and hosting companies, like Ungleich.ch Data Center Light and Mythic Beasts, are now operating IPv6-only core networks for operational simplicity.

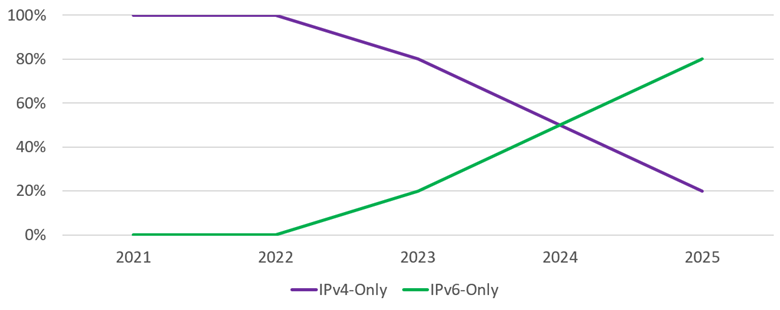

This is some of the thinking and justification behind some government IPv6 mandates. The U.S. Federal government Office of Management and Budget (OMB) published a mandate in November 2020 (M-21-07) that re-emphasizes the importance of IPv6 for government departments and agencies and sets forth a schedule to disable IPv4. The schedule is to have 20% IPv6-only by end of FY 2023, 50% IPv6-only by end of FY 2024, and 80% IPv6-only by end of FY 2025 (see graph below). The thought here is that by the 80% stage, the Internet will be predominantly using IPv6. The State of Washington has an IPv6 “Policy 300” to disable IPv4 by the end of 2025, and the Chinese government has a 100% IPv6 goal by 2025.

As your enterprise begins to consider a migration to IPv6, the architecture and design should not aim to end in the middle-term, dual-protocol state, but instead should chart a course through to the eventual IPv6-only goal. The “Lessons Learned and Recommendations from IPv6-Only Deployments” have been documented by a few organizations (part 1, part 2). The benefits of IPv6 are realized when taking a long-term view of the transition and planning accordingly.