Back in January of this year (2021), something happened that caused a commotion in the networking community. The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), via BGP proxy AS8003, advertised a vast amount of IPv4 address space that had been previously unannounced. This event got me thinking about several topics – and offers me an excuse to climb up on a soapbox and discuss a few subjects related to IPv4, IPv6, best practices, and an antiquated security mindset.

The DoD announcement

Numerous other blogs, podcasts, and articles have covered the surprise DoD action, and I will not go into detail here. (There is a good synopsis on Kentic’s web site.) But to provide a quick overview, back in January, the DoD started advertising to the Internet previously unannounced IPv4 address space from a seemingly dormant, mysterious company. In the months thereafter, AS8003 continued to advertise more and more DoD IPv4 CIDR blocks until they were originating 764 prefixes (including multiple /8s), accounting for roughly 175 million IPv4 addresses. Conspiracy theories immediately popped up. Was the space hijacked? (It turns out that was not the case.) Was the DoD preparing to sell their wealth of IPv4 assets? Was it a honey pot to collect and analyze stray packets? Or, possibly, a combination of the last two? (In a semi-official comment from the DoD’s Defense Digital Service, they stated the act was a “pilot effort” to “assess, evaluate, and prevent unauthorized use of DoD IP address space…” that also “…may identify potential vulnerabilities.”)

Conspiracy theories aside, one thing is for certain: it caught nearly everyone off guard. Several large enterprises, and even some service providers, use the DoD space internally. Most had exhausted IPv4 addresses, both public and private, and were scouring the IPv4 world for “free” numbers to use for internal purposes.

The DoD had a hand in creating the Internet, and most network engineers know they have a vast portfolio of IPv4 resources – and seemingly would never advertise that space publicly. So, despite their better judgment, organizations started using DoD blocks internally. Now those entities are in a pickle. Do they really know where their internal endpoint packets are going when they are destined for a server in 7.0.0.0/8? Or what do they do if the DoD does sell all or part of their IPv4 assets? Azure or AWS could purchase blocks and use them for their IaaS clients – forcing squatters to re-number or risk losing access to legitimate Internet services. Obviously, this is not the best position for organizations to be in. Nor is it ideal for the DoD to have numerous networks using their addresses.

The “security through obscurity” mindset

This DoD event brought to fore the topic of advertising one’s address space. Or more specifically not advertising it. Over the years I have come across numerous companies that opt to not advertise parts of their Provider Independent (PI) address space. The reasoning is almost always that “it is more secure” to not advertise IPs to the public Internet. I suspect this comes, at least in part, from decades of network engineers using RFC 1918 addresses and NAT for public Internet access, and the security model that accompanies this architecture. The thought is “if something is hidden, it is safer.” There is some truth to this, but in current networking, its validity is conditional at best. Network Address Translation and RFC 1918 addressing were developed to prolong limited IPv4 resources, not as a security mechanism. It may be widely accepted as such, but we know how exploits regularly circumvent this common design. And a strong argument can be made that, along with a false sense of security, the added complexity of NAT can lead to misconfiguration and other administrative errors that exacerbate risk (not to mention the problems sorting through logs and translating addresses during incident triage).

Security experts make the case that topology-hiding is not a cornerstone of IT security. Using NAT and RFC 1918 address space does not specifically provide security, rather stateful inspection provides this function at the perimeter or on the host. This is discussed in RFC 4864, Local Network Protection for IPv6. And of course, the perimeter is only one aspect of a broader security strategy and framework.

Announce your IPv4 address space

For those enterprises that have an IPv4 Provider Independent (PI) allocation, it should be viewed as a valuable asset. All five Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) have exhausted their IPv4 address pools. Enterprises need to protect their PI space for internal use since acquiring more from their RIR is not an option. Or, if it is not needed, they can sell it on the gray market to an entity that can justify the transfer. (A note about the example above – the DoD’s IPv4 CIDRs could be worth north of $7 billion based on the current price of $40 per IPv4 address.)

My recommendation is to protect this asset by announcing it through your transit peers to the public Internet. If all or part of that announcement is not intended for public use, the route can simply be blackholed at the network perimeter, eliminating the attack surface. Having your CIDR(s) in the global table will discourage others from using those blocks for internal use, or worse yet, from squatting on them publicly. The advertisement of the DoD IPv4 address space could be a warning to organizations using DoD numbers internally that the practice should be discouraged and is not a long-term strategy for those entities. The perceived benefit of not advertising is more than offset by drawbacks and risks of not doing so.

Another reason to advertise the DoD IPv4 addresses may be to put them into the Internet routing tables to show proof of ownership and use as part of a preparatory step to a sale. The IPv4 address transfer market pricing is often based on the cleanliness and reputation of those numbers. The DoD could be advertising these addresses to assess and prove their reputation to derive maximum value of these assets. The DoD would want to get top dollar for these addresses, but if they are squatted on frequently and there is significant “backscatter” from their use on the Internet, then the price per address could be lower than the DoD desires.

The industry has seen organizations run out of RFC1918 address space, and now many are starting to use RFC 6598 addresses (incorrectly applied), and, as we have seen, some are using DoD and/or other allocated but unadvertised blocks. Organizations are desperate, not following networking best practices, and grasping at straws. Do not let them take your straw!

Or better yet… IPv6

If the DoD had started announcing a block of IPv6 address space, would that act have also caused such a fuss? I suspect anyone that even noticed would not have given it a second thought. Most of the discussion above has revolved around IPv4 networking and all the architectural, security, financial, and philosophical baggage that come with it.

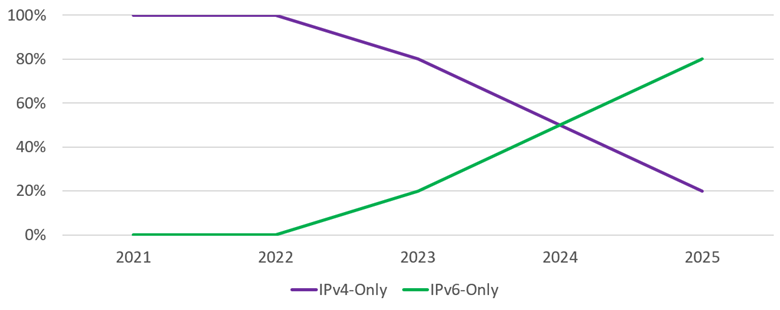

One way to circumvent all these issues is to simply deploy IPv6 – architect your network for the future and let go of the past. Many others have taken this step. Previously I wrote about best practices and lessons learned from companies that have gone IPv6-only. We know that IPv4 will be around for a while, but there are numerous ways for IPv6-only networks to communicate with the legacy Internet. IPv6 brings back the end-to-end nature of the Internet, which is much simpler and easier to operate. It can be secured without NAT, and it is also a model that fits well with zero trust networking. It is, in almost every manner, superior and leads one to ponder why we are still dealing with all the IPv4-related issues discussed above.

Conclusions

It is recommended that if you do have PI space from your RIR to advertise that block in the default free zone. If that space is not to be accessed from the public Internet, simply blackhole the route. And follow other best practices related to your valuable IP assets such as keeping Internet Route Registries current, as well as maintaining your organization’s information in RIR databases. (For ARIN, you can find related information here.) In addition, use an IPAM system to properly manage your IP assets internally.

As the cost of IPv4 address continues to increase, and companies start to employ more desperate measures, leave the drama behind, and embrace IPv6. IPv6 brings back the end-to-end nature of the Internet by simplifying designs and often improving network performance. Stateful security and a zero trust network architecture can be employed to secure corporate assets in IPv6, just like IPv4. Your RIR has plenty of IPv6 address space to allocate your organization to get started, and lots more for future growth if needed. And when an IP-rich entity like the DoD starts advertising large swaths of IPv4 address space, you can safely ignore the news and move on to more pressing tasks.