Author: Renée Burton and Dave Mitchell

This blog is based on collaboration between Infoblox Threat Intel and co-author, Dave Mitchell. The campaign research reported here was completed in January 2024, while our findings on DNS amplification cover the past year.

A global scale domain name system (DNS) probing operation that targets open resolvers has been underway since at least June 2023. We analyzed queries to Infoblox and many other recursive DNS resolvers in January 2024. While there are numerous commercial and academic DNS measurement operations conducted daily on the internet, this one stood out because of its size and the invasive structure of the queries. These probes utilize name servers in the China Education and Research Network (CERNET) to identify open DNS resolvers and measure how they react to different responses. The name servers return random IP addresses for a large percentage of queries. The random IP values trigger an amplification of queries by the Palo Alto Cortex Xpanse product. This amplification pollutes passive DNS collections across the globe and hinders the ability to perform reliable research on malicious actors.

We and other researchers previously coined this actor Secshow based on the initial domain names that were used. This blog describes Secshow’s probing operation as we understand it today and the problems caused by DNS amplification.

We first encountered Cortex Xpanse amplification in April 2023 while collaborating on Decoy Dog research. While we would not normally “call out” a security vendor publicly, the negative impact of Cortex Xpanse amplification continues and has led multiple researchers to draw false conclusions due to polluted passive DNS. Understanding Decoy Dog and other malicious activity from global passive DNS sources is impossible due to this pollution. Xpanse’s amplification not only confuses researchers but can assist attackers in reconnaissance. It also creates a resource burden on DNS providers globally; Infoblox saw a nearly 200-fold increase in Secshow queries in January 2024 due to Cortex Xpanse amplification. The amplification, pollution, and misdirection has created its own security show for the industry, and especially those who use DNS to identify malicious behavior and protect their networks.

What is Secshow?

Secshow is the name we gave to a Chinese actor operating from the China Education and Research network (CERNET) and conducting global-scale DNS probes. These probes seek to find and measure DNS responses at open resolvers. An open resolver is a device which, typically through misconfiguration, will either resolve or forward any DNS query it receives on the internet. Open resolvers create a vulnerability in a network and are frequently used for DNS distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks.

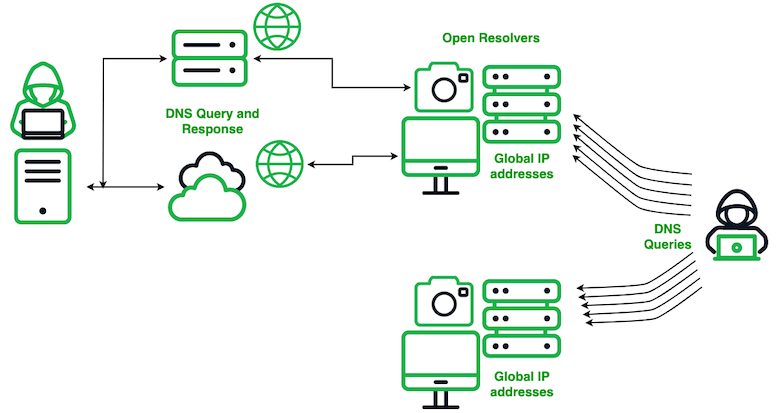

We use the term probe versus scan because the latter is too often interpreted as an inherently harmless activity to collect public information. Probes on the other hand use active interrogation methods to obtain private information about a network, its configurations, and vulnerabilities. The end goal of the Secshow operations is unknown, but the information that is gathered can be used for malicious activities and is only for the benefit of the actor. The diagram in Figure 1 shows a simplified version of Secshow’s DNS probing operations.

Secshow operators send DNS queries to IP addresses around the world, including both IPv4 and IPv6; we call these the targets. We are not able to determine where the queries originate, but they contain encoded information including the target IP address and a date or timestamp. These queries request IPv4 or IPv6 addresses for the domain from the target IP address. When the target receives an IP packet containing a DNS query, several things may happen, including:

- If the target device is an open DNS resolver, it will resolve the query and return a response.

- If the target device is not an open resolver or another device intercepts the packet, e.g., a firewall, an ICMP response may be created and sent back to the source IP address.

- If the target device is not an open resolver, it might forward the response to another resolver.

In our experience, broad spectrum DNS scans or probes can cause a wide range of side effects, not all of which can be easily explained or outlined in a bulleted list. This is especially true in networks containing internet-facing devices that are not designed to receive DNS queries, for example home routers or internet-of-things (IoT) devices.

Figure 1. A simplified view of the Secshow DNS probing operations; open resolvers result in queries sent to the Secshow actor for resolution

Infoblox first detected Secshow activity in early July 2023. At the time, the activity had low volume in our customer networks because there are few open DNS resolvers in our customer base. However, through fall 2023, the volume of queries we observed grew dramatically. In early January 2024, we began a collaboration with a few other researchers, and Dave was able to determine from global passive DNS sources that the queries contained encoded IP addresses, and that these IP addresses were often open resolvers. He also identified timestamps in the queries. Unfortunately, his observations explained only a small portion of the DNS queries that were received at the Infoblox recursive resolvers. Digging deeper into Infoblox activity, Renée was able to determine that the confluence of two forces were causing the alarming volume of activity: wildcard configurations by the Secshow actor and unfiltered scanning by Palo Alto Cortex Xpanse. We will explain the impact of both factors in this paper.

Others have recently reported on Secshow, sharing what they have learnt from their visibility and experience. Dataplane.org described destination-adjacent-source-address (DASA) spoofing that they observed between August 2023-January 2024, in which a modest number of IP packets were received purportedly from devices near to their DNS resolvers.1 They used IP packet time-to-live (TTL) values to determine that the packets most likely originated from Eastern Asia, consistent with a source in CERNET. Broadscale DASA source spoofing is not easily accomplished due to egress filtering applied at most network boundaries. This filtering ensures that the traffic leaving the network contains source IP addresses within the network and is designed to address distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks from spoofed IP addresses.

Palo Alto Unit 42 also included Secshow in a recent report.2 Our findings are similar in many ways, but there are some important differences. Our visibility and experience with similar operations led us to draw different conclusions about information embedded in the DNS queries. The amplification of Secshow queries by Xpanse makes the data difficult to correctly interpret and can easily mislead a researcher. Nevertheless, we are confident in our results because we can compare the data directly at Infoblox and other DNS recursive resolvers.

Secshow Query and Response Details

As of mid-May 2024, Secshow name servers are not responsive. The behavior described here is as of January 2024.

The Secshow actor controls multiple domains including:

- secshow[.]online

- secshow[.]net

- secdns[.]site

The name servers for these are hosted in IP space assigned to the CERNET (AS538) and the domains were registered between June and December 2023. Infoblox first observed a query from the Secshow actor on July 1, 2023. Secshow uses actor-controlled name servers to record responses from its probes, as well as trigger on secondary actions by open resolvers.

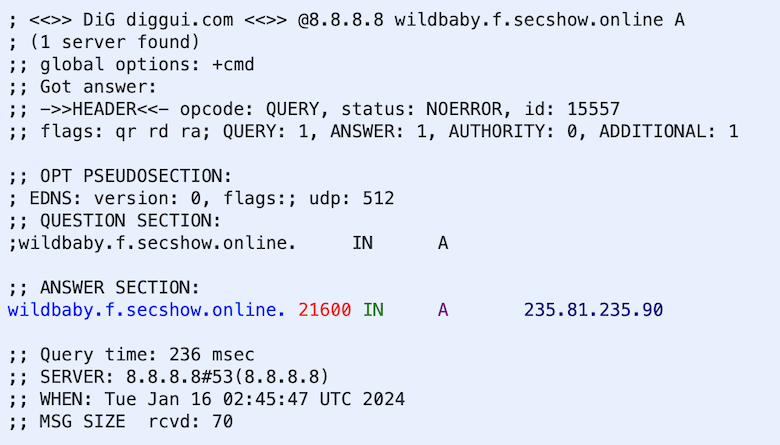

Secshow name servers were configured to provide selective wildcard DNS responses, meaning that the name server will respond to any query that is of the proper format. For example, within the domain secshow[.]online a query that included the subdomain “f” would return a random IP address. In Figure 2 we show an example where the hostname “wildbaby” returned an IP address of 235[.]81[.]235[.]90. We performed these experiments using many different resolvers and a new IP address was returned each time. The name server did not respond to queries that did not include the proper subdomain, in this case “f”.

Figure 2. Demonstration of wildcard responses by the secshow[.]online name server

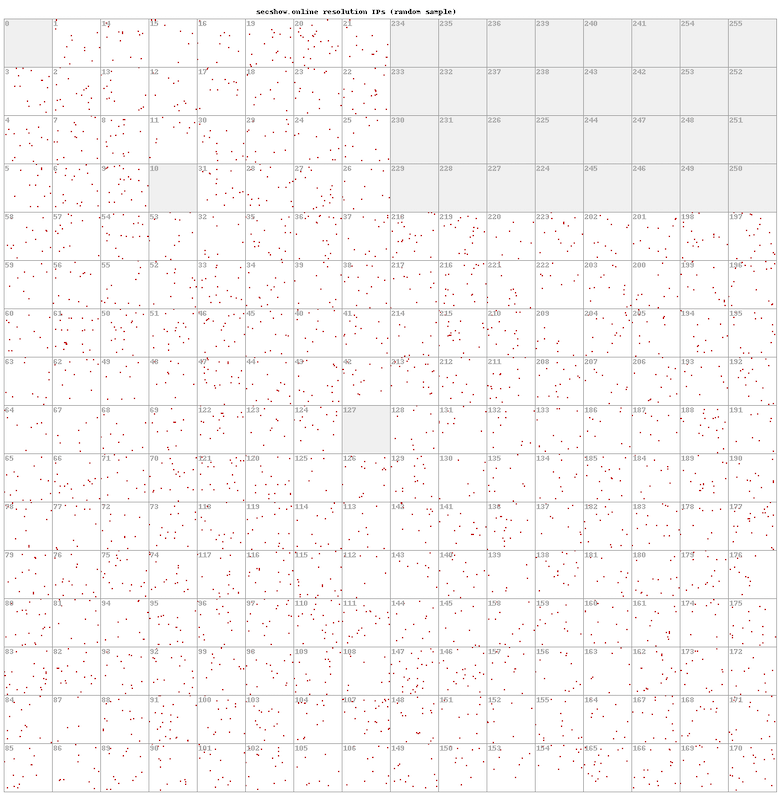

As a result of selective wildcard responses, the global set of resolution IP addresses for Secshow domains was extremely broad and consistent with what may be seen in a DNS malware command and control (C2) beacon. It is unknown why the name server returns random IP addresses or uses wildcard configurations. The same behavior was seen for IPv6 queries. Figure 3 shows the distribution of resolution IPv4 addresses in January 2024 for the domain secshow[.]online using a Hilbert map for visualization. This distribution is consistent with a random IP address that excludes the reserved space in IPv4.

Figure 3. A random sample of IPv4 addresses seen in DNS responses for secshow[.]online in January 2024. This chart uses a Hilbert map to show the entire IPv4 space. Each red pixel is a single IP address that was returned from the name server to a query.

Queries are sent from an unknown origin on the internet to broadly distributed target IP addresses. These queries have different formats and some of the formats have changed over time. Some of the formats are:

- <hex-encoded-target-ip>-test.l.secshow[.]net

- <int>-<target-ip>-<ip2>.f.sechow[.]online where target-ip and ip2 are IPv4 addresses separated with hyphens, e.g., 08-08-08-08

- <int>-<hex-encoded-ip>-<date/timestamp>-query-maxttl.l-httl.secshow[.]net

- <date/timestamp>.bailiwick.secshow[.]net

In addition to the keyword “query” in hostnames, we observed “ans”, “timeout”, “minttl”, “maxttl”, “dstip”, “icmp”, and others.

Encoding IP addresses in DNS query names is a common technique used to convey information to the authoritative name server. It has been used for both malicious and benign purposes. Several DNS measurement projects encode IP addresses in their DNS queries. For example, the University of Twente scans the internet for open resolvers using the domain openresolve[.]rs.3 Their queries have the format:

- <target-ip >.<timestamp>.main.research.openresolve[.]rs

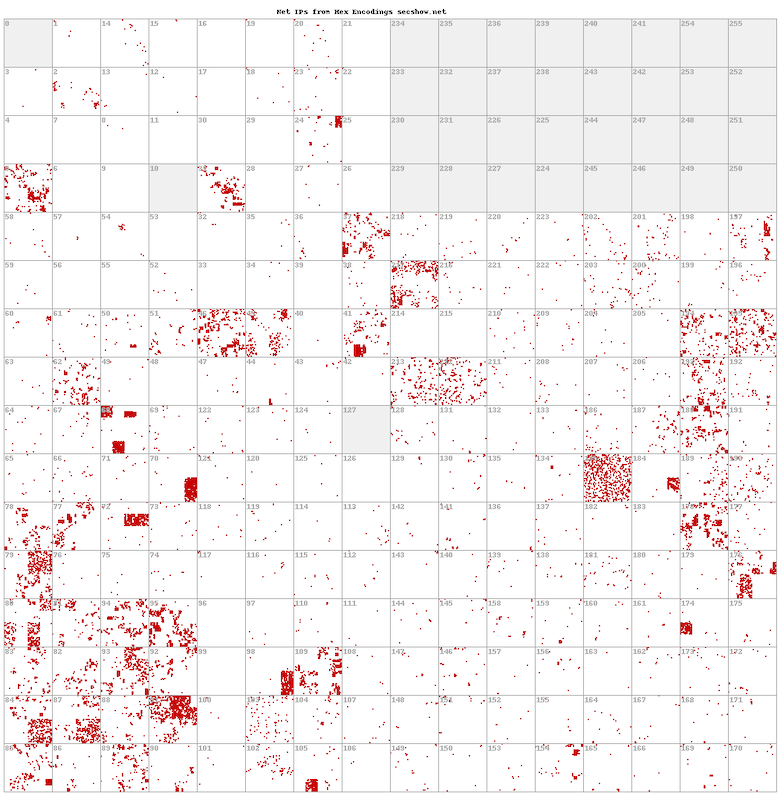

We were able to confirm that the hex-encoded IP addresses within the query were the target IP addresses. That is, a DNS query was sent to these IP addresses by the Secshow actor to see if the query would resolve. The encoded IP addresses are not spoofed IP addresses. Using large-scale response data across Infoblox and other passive DNS collections, we verified that the encoded IP addresses were open DNS resolvers. Of note, we found many IP addresses used by MikroTik routers encoded in the DNS queries, but the complexity of modern networking makes identifying the nature of most open resolvers or their routes to authoritative name servers difficult. Figure 4 offers a visualization of the breadth of Secshow’s targeting. This chart shows a Hilbert map of encoded IP addresses observed in combined passive DNS sources.

Figure 4. The distribution of IP addresses encoded in Secshow DNS responses. Each red pixel is an encoded IPv4 address. Large concentrations of red indicate a block of IP addresses that were observed in queries.

The Secshow actors perform several different tests against target resolvers. Unit 42 researchers had noted the presence of the domain afusdnfysbsf[.]com in responses to certain queries. These responses are the result of a DNS delegation name (DNAME) record. The domain is not registered, and the DNAME record and related IP address were provided as additional “glue” records from the name server. Most DNS resolvers would attempt to resolve the domain name itself and receive an NXDOMAIN response from the TLD server, but some could cache the result without confirming the record.

Secshow also uses CNAME responses to trigger additional queries by the recursive resolver. This can allow them to test the resolver’s handling of CNAME records and measure time of round-trip results. For example:

- The IPv4 query for

0-<target-ip>-202404111-40-query-timeout.l-time[.]secshow[.]net - would receive a CNAME record in response with the value

0-<target-ip>-202404111-40-ans-timeout.l-time[.]secshow[.]net - which would trigger the recursive resolver to resolve the CNAME record value to an IP address.

Using CNAME and DNAME records can provide Secshow with precise information about the recursive resolvers involved. Additional query names hint at an array of other measurements of the resolvers and the resolution path.

Dataplane.org also reported queries using unregistered domains of the form

These queries would receive an NXDOMAIN response from the comTLD server. This type of query can be used to check a resolver’s negative caching policy, in which they cache the NXDOMAIN response for some period to avoid further failed lookups. Understanding how individual resolvers handle negative responses can be used in denial-of-service attacks.

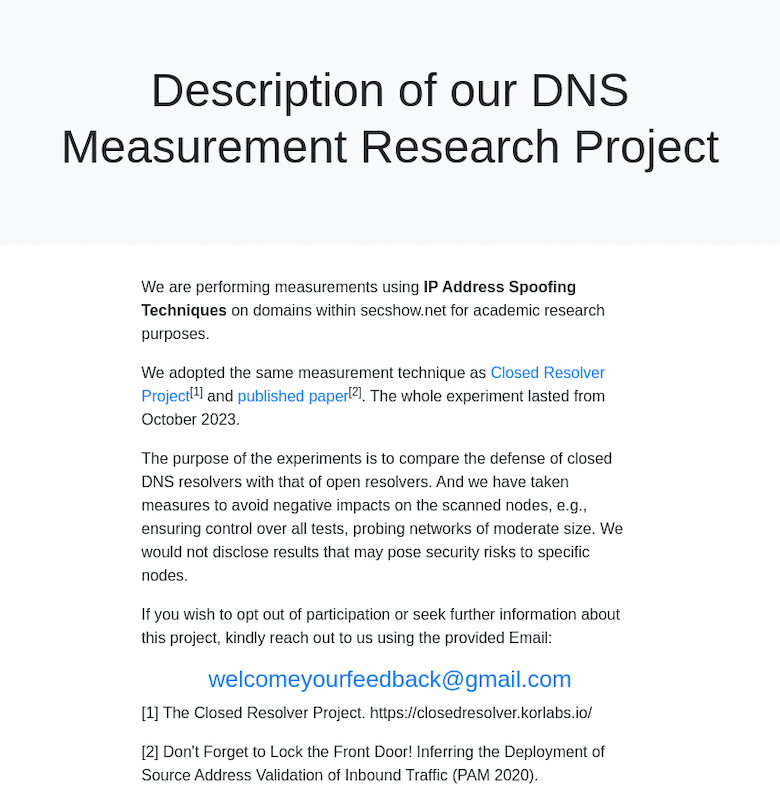

According to a Google search engine result, shown in Figure 5, the Secshow actor is performing research to identify vulnerable DNS resolvers.4 On the website, the actor claims to implement the experiments documented by DNS researchers in 2020, which used scans to identify DNS resolvers susceptible to IP spoofing attacks due to a lack of source address validation (SAV).5 The page raises several questions.

- Why is the research organization not identified?

- Why are only part of the methods they use documented?

- What is the full scope of their “research”?

- Why are they using a generic Gmail address for research feedback?

- Why claim the project began in October 2023, when we know it began in July 2023?

- How are they using the data?

Figure 5. A Google search engine crawl of secshow[.]net shows that the actor was performing research on DNS resolvers

Cortex Xpanse Amplification

Our analysis of Secshow and our ability to understand their impact on global networks was hindered by the behavior of Palo Alto’s Cortex Xpanse product. Cortex Xpanse is an “active attack surface” management product that amplifies certain DNS activity, some of which is malicious. We initially encountered the effect of Cortex Xpanse amplification while researching the DNS malware Decoy Dog in March 2023, and since then we have collaborated to investigate other suspicious DNS traffic only to find that the results were polluted by artificial queries from Cortex Xpanse.6 Infoblox has notified Palo Alto of the adverse impacts of Cortex Xpanse behavior on the threat intelligence community on multiple occasions, most recently in January 2024 when we reported Secshow to the company. We are unaware of the specific operational details of the product and suggest readers contact Palo Alto directly for information beyond this documentation of impact.

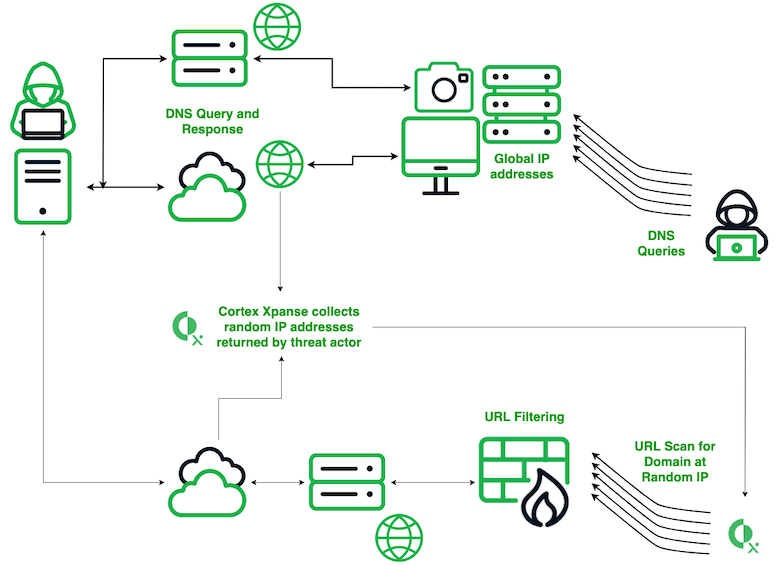

The amplification of Secshow queries is due to a combination of the random IP addresses returned by the name servers and the Xpanse behavior. Based on an initial tip from Veloxity via LinkedIn last year, we have validated how this amplification works.7 The bullets below and Figure 6 provide an overview of the amplification.

- The Secshow actor sends a DNS query to an open resolver and the Secshow name server returns a response containing a random IP address.

- The DNS response is visible in multiple locations on the internet and is somehow collected by Cortex Xpanse.

- Cortex Xpanse treats the domain name in the DNS query as a URL and attempts to retrieve content from the random IP address for that domain name.

- Firewalls, including Palo Alto and Checkpoint, as well as other security devices, perform URL filtering when they receive the request from Cortex Xpanse. This filtering triggers a new DNS query for the domain.

- The Secshow name server returns a different random IP address.

- This cycle repeats, with the Cortex Xpanse behavior potentially turning a single Secshow query into an endless cycle of queries in networks around the world.

- Additionally, Cortex Xpanse makes the URL scanning attempt repeatedly over some period of time creating a multi-fold amplification from a single original DNS query.

Figure 6. How Cortex Xpanse amplifies Secshow DNS queries globally when name servers return random or false IP addresses in response to DNS queries

While open resolvers are occasionally detected in Infoblox customer networks, the number is small. So how did we discover the amplification?

- We knew from large-scale analysis that the IP addresses encoded in queries were target IP addresses and that the IP addresses should be open resolvers.

- We decoded the IP addresses found in queries to the Infoblox recursive resolvers that were forwarded from our customers.

- Those IP addresses rarely matched our customer IP space, and in many cases, they were Chinese IP addresses.

- We saw the same queries repeated over time, sometimes from completely unrelated customer networks.

- We were able to match queries from global passive DNS queries to those seen at our resolvers; this is the same behavior we observed with Decoy Dog amplification.

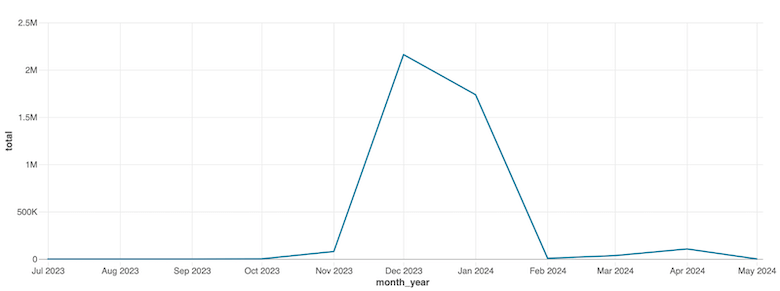

Figure 7 is a graph of the impact of Cortex Xpanse amplification on Infoblox customer networks. While Secshow organically induced, via open resolvers, six queries in July 2023 in our customer networks, we saw over 2.3M queries, almost entirely from Cortex Xpanse amplification, in December 2023. At Infoblox resolvers, we have observed Xpanse repeatedly making the same URL scan and triggering multiple queries over time.

Figure 7. The impact of Cortex Xpanse amplification on Infoblox customer networks. Within Infoblox customer networks, there were 6 organic queries in July 2023 induced by the Secshow actor, and over 2.3M queries in December 2023 induced almost entirely by Cortex Xpanse. The first query observed at Infoblox resolvers was July 1, 2023.

Why are these queries in my network?

Open DNS resolvers are a serious vulnerability for any network, and it is important that they be identified and closed. Queries for any Secshow domains in your DNS logs are due to one of two things:

- An open resolver exists in the network, or

- Cortex Xpanse has scanned your network based on random IP addresses returned by the Secshow actor

To determine whether the queries are the result of an open resolver:

- Locate the embedded IP address in the query as either an 8-long hex-encoded string or a hyphen delimited representation.

- Decode or extract the IP address and match it to your known IP space.

- If the IP address is within your IP space and externally facing, the device at this IP address is acting as an open resolver and you should remediate.

- If the IP address is within your IP space but is internal, or the IP address is unrelated to your network, the queries are likely due to scans by Xpanse.

Conclusion

While the Secshow operations have ceased recently, they demonstrate the power of DNS probing done by an actor with access to the internet backbone. Secshow performed large-scale DASA spoofing to probe IP space worldwide over several months. Their probes sought information about the configuration of open resolvers and networks that can be used for malicious activities, including several query types seemingly intended to identify detailed information about the resolver’s caching of responses. The actor provided incomplete information about their probes and did not reveal their identity. While Secshow may be conducting academic experiments, they are not following standards of academic disclosure. All members of the security industry should transparently document active probing methods, whether they be academic or commercial in nature, to avoid wasting security and network teams’ time and resources.

The amplification and consequential polluting of passive DNS collections by Cortex Xpanse has hindered the analysis of multiple threat actor

s over the last 15 months. In addition, this aggressive and indiscriminate scanning serves to further malicious actor reconnaissance and directly increases costs to networks around the world, including DNS processing and storage costs. The inability for Cortex Xpanse to identify wildcard DNS responses or DNS malware and to stop scanning those domains for their attack surface management makes their product a burden on defenders around the globe. The lack of complete documentation by Cortex Xpanse has, like Secshow, caused security teams and researchers to spend resources chasing phantom malware.

Secshow is only one of the Chinese actors we have observed this year performing large-scale DNS probing activities. At the same time as we were collaborating on an analysis of Secshow DNS traffic, Infoblox was researching another actor, Muddling Meerkat. Muddling Meerkat is a Chinese nation state actor with the ability to control China’s Great Firewall to elicit unusual DNS MX record responses. While both actors demonstrate a strong understanding of DNS probe networks globally, we have no reason to believe these are the same actor. Muddling Meerkat queries are designed to mix into global DNS traffic and remained unnoticed for over four years, while Secshow queries are transparent encodings of IP addresses and measurement information.

Indicators of Activity

Secshow controls these domains:

- secshow[.]online

- secshow[.]net

- secdns[.]site

- prey[.]fit

- attacker[.]fit

- nameserver[.]fit

- victim[.]fit

- savme[.]xyz

Footnotes

- https://blog.apnic.net/2024/04/19/destination-adjacent-source-address-spoofing/

- https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/three-dns-tunneling-campaigns/

- https://research.openresolve.rs/

- The date of this search engine crawl is unknown, and the website is not responsive in mid-May 2024

- Don’t Forget to Lock the Front Door! Inferring Deployment of Source Address Validation of Inbound Traffic, Korczyński, et al., 2020 https://arxiv.org/pdf/2002.00441 (last accessed May 22, 2024)

- https://live.paloaltonetworks.com/t5/general-topics/spurious-hits-from-the-expanse-webcrawler/td-p/447239 last accessed 2024-05-20

- https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7052364929554657280?commentUrn=urn%3Ali%3Acomment%3A%28activity%3A7052364929554657280%2C7053742397133852673%29&dashCommentUrn=urn%3Ali%3Afsd_comment%3A%287053742397133852673%2Curn%3Ali%3Aactivity%3A7052364929554657280%29 last accessed 2024-05-020