Recently, I shared the first blog in a series recounting a user’s experience with malicious adtech. In that blog, I described how I had visited a compromised website, allowed notifications and found myself inundated with a seemingly endless stream of malicious content. For over three months, I had recorded every interaction and analyzed how the different companies in the adtech world affiliate with each other and with the advertisers they serve. In that initial blog, I shared my experience with how actors use malicious adtech to deliver scareware; in this one, I’m going to show how malicious adtech delivers gift card, sweepstakes and survey scams.

If you already read that first blog, feel free to skip ahead to the “Gift Cards and More” section. For those joining for the first time, here is a quick recap:

When you visit a website that requests your permission to send notifications and you agree to receive them, you are giving the site the ability to “push” advertisements to your screen whenever they choose. Push notifications can be weaponized and used as a gateway to fraud and malware. The advertising industry markets push notifications as an “opt in” service for users to keep up to date with a website’s offerings, but deceptive practices can cause users to accept notifications without fully realizing it.

Threat actors alter compromised websites so that the visitor will be tricked into accepting push notifications, not from the original site but from a dubious service. Once the visitor accepts, they are bombarded with notifications that lead to a variety of malicious and unwanted content. Messages crafted to look like trusted sources are designed to drive the user to respond out of fear or hope. For example, the message may imitate Google and claim the user’s account has been hacked or pretend to be Walmart delivering a gift card. Interacting with these fraudulent messages leads to new content, often to accept more notifications, and pulls the user further into a cybercriminal rabbit warren.

While malicious push notifications are an easy problem to solve from a technical perspective—the user simply needs to unsubscribe—they are lucrative for malicious actors. Before realizing they have been duped, users often take the bait, downloading harmful applications or handing over credentials. Worse, the criminals often advertise their own fake apps or antivirus services to fix the problem they have created. Consumers who are conned into buying subscription services, whether it be for security, dating or a product, are often forced into an endless subscription and harassment model where their credit card is charged repeatedly, and the service company sends threatening emails after cancellation.

Compromised websites fuel the malicious adtech industry by integrating push notifications that continue the exploitation of the user after leaving the site. Threat actors can target users from every corner of the world and every walk of life by hacking legitimate sites and injecting code that will ask the user to accept notifications. Websites that are vulnerable to these attacks are plentiful: Infoblox Threat Intel has seen everything from scientific research sites to car dealerships to activist blogs taken over by cybercriminals. We even discovered an entire website service provider’s offering that had been hacked. Industry experts estimate that millions of websites are compromised each year, and from our own experience, we’ve seen sites hacked repeatedly and attacks that have gone undetected for months.

To evade detection from the security industry, threat actors use domain cloaking and traffic distribution systems (TDSs) to vary whether the content that is delivered is benign or malicious. A cunningly designed TDS can fool security teams and allow compromises to persist for extended periods of time. A user who revisits the same site is not likely to receive the same content and push notification requests a second time, making it hard to determine the source.

Gift Cards and More

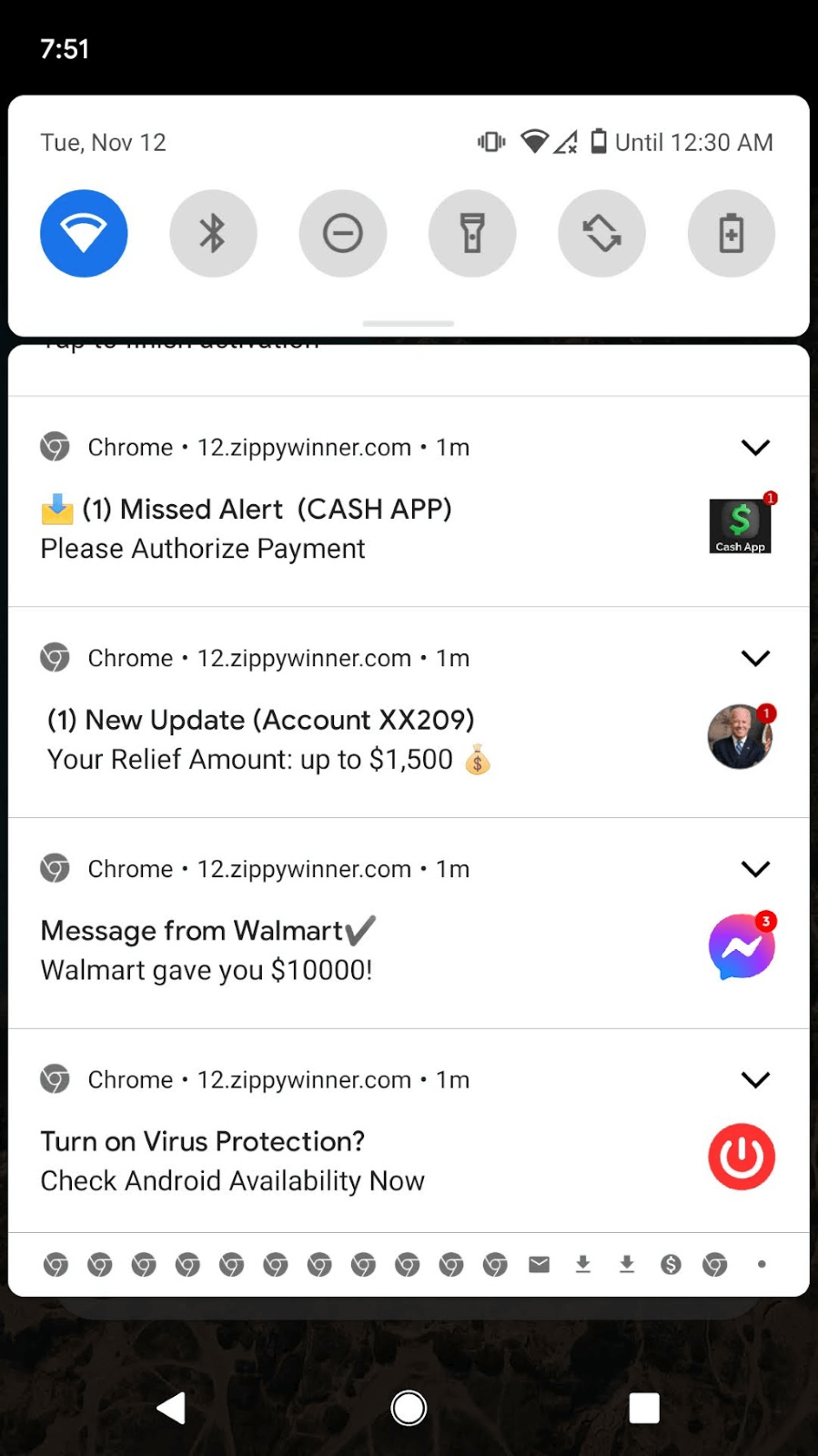

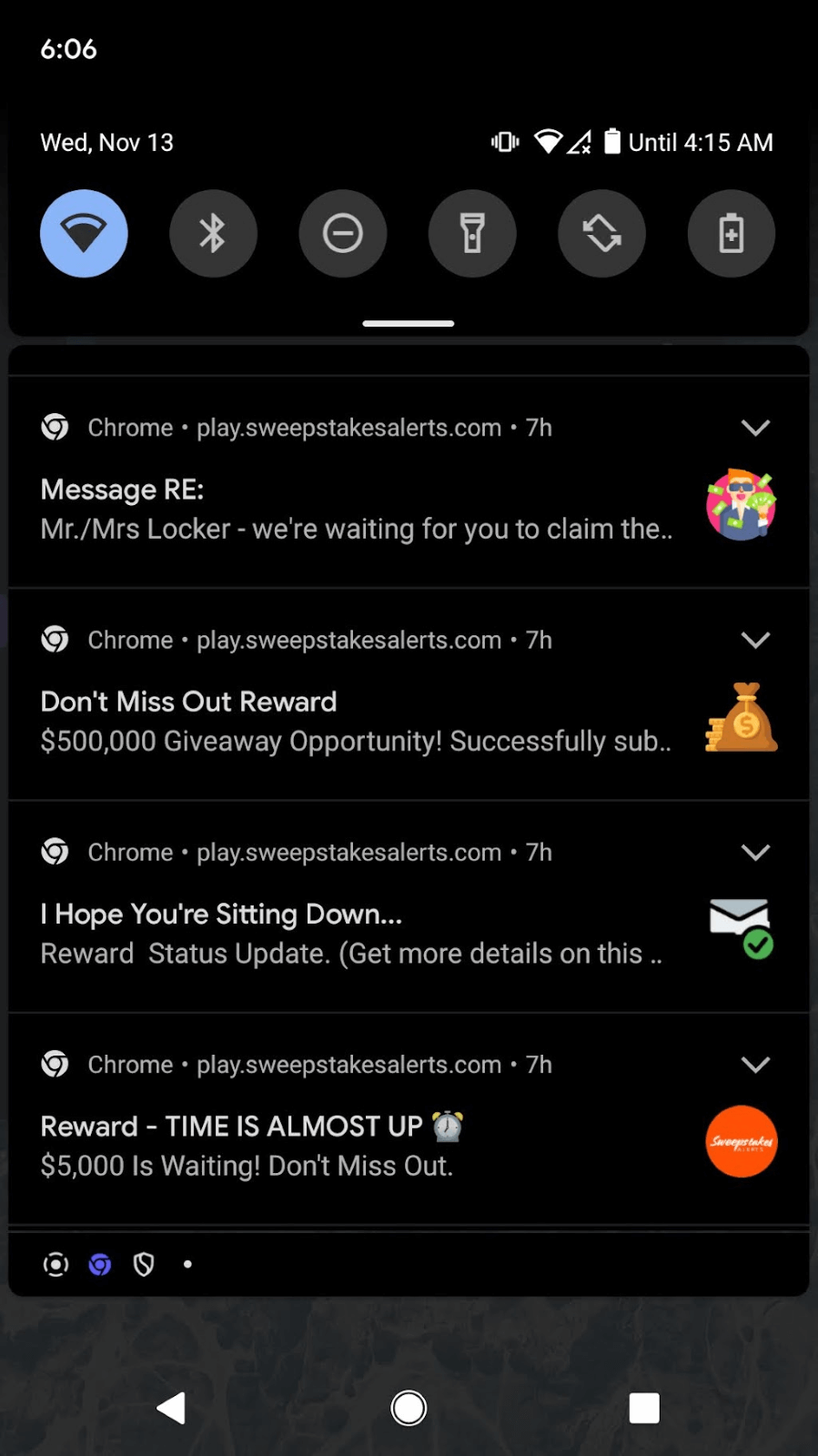

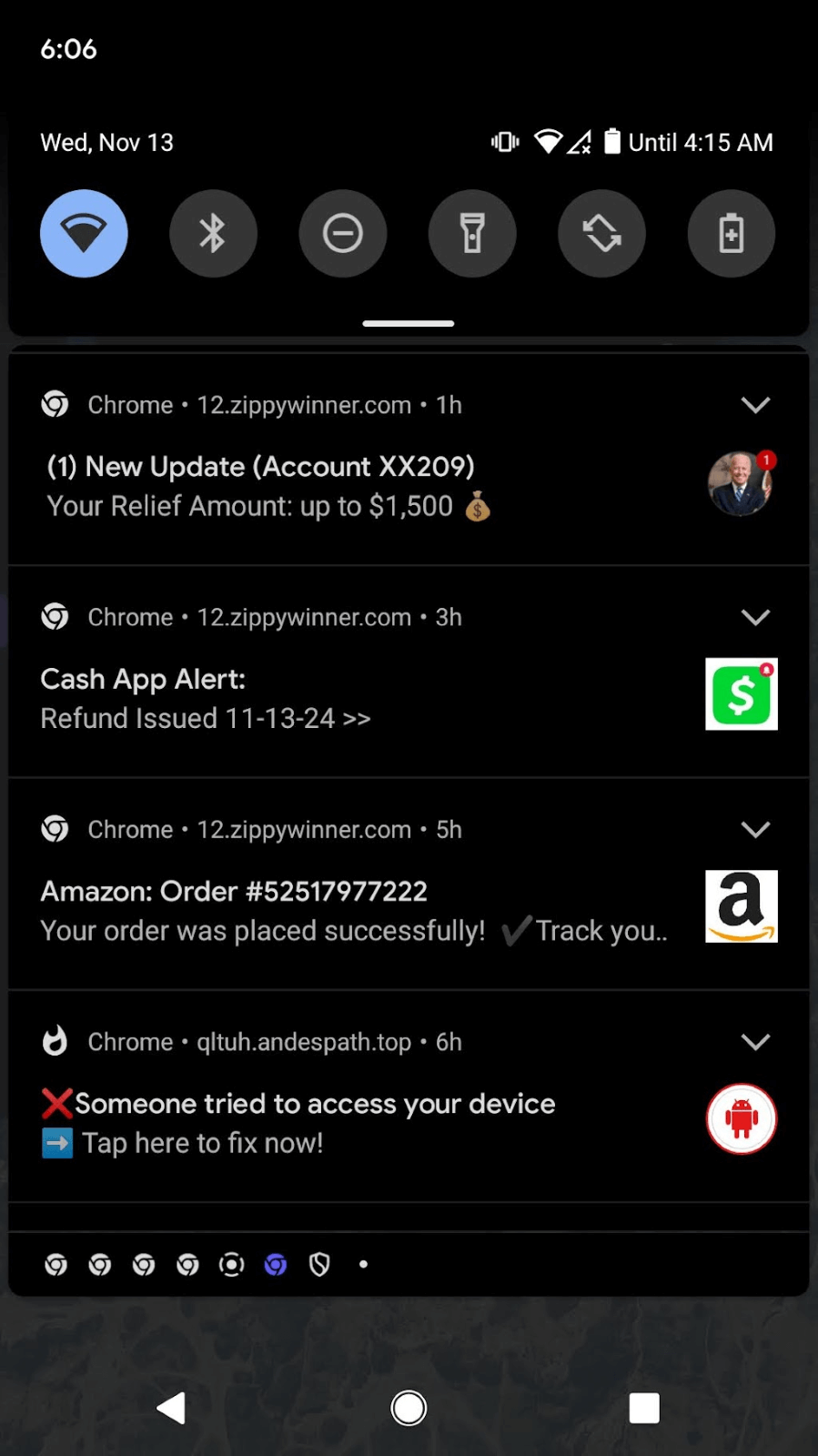

Scammers lure users with messages that prey on their desire to win money. The pop-up might say “Walmart gave you $10,000! Please authorize payment,” promise government funding or any number of other promising messages. Usually, you receive several messages at once with slightly different temptations. See some examples from my phone in Figure 1. When I clicked on a notification, it routed me through several different domains via a TDS before landing at the final website. As a user, you don’t see all the domains that are contacted in this process and the ones you do see fly by the screen so fast you likely can’t read them. I took a lot of screen captures to record the path my browser took.

Figure 1. Example of rewards notifications. One site will usually deliver several messages at a time intermittently throughout the day.

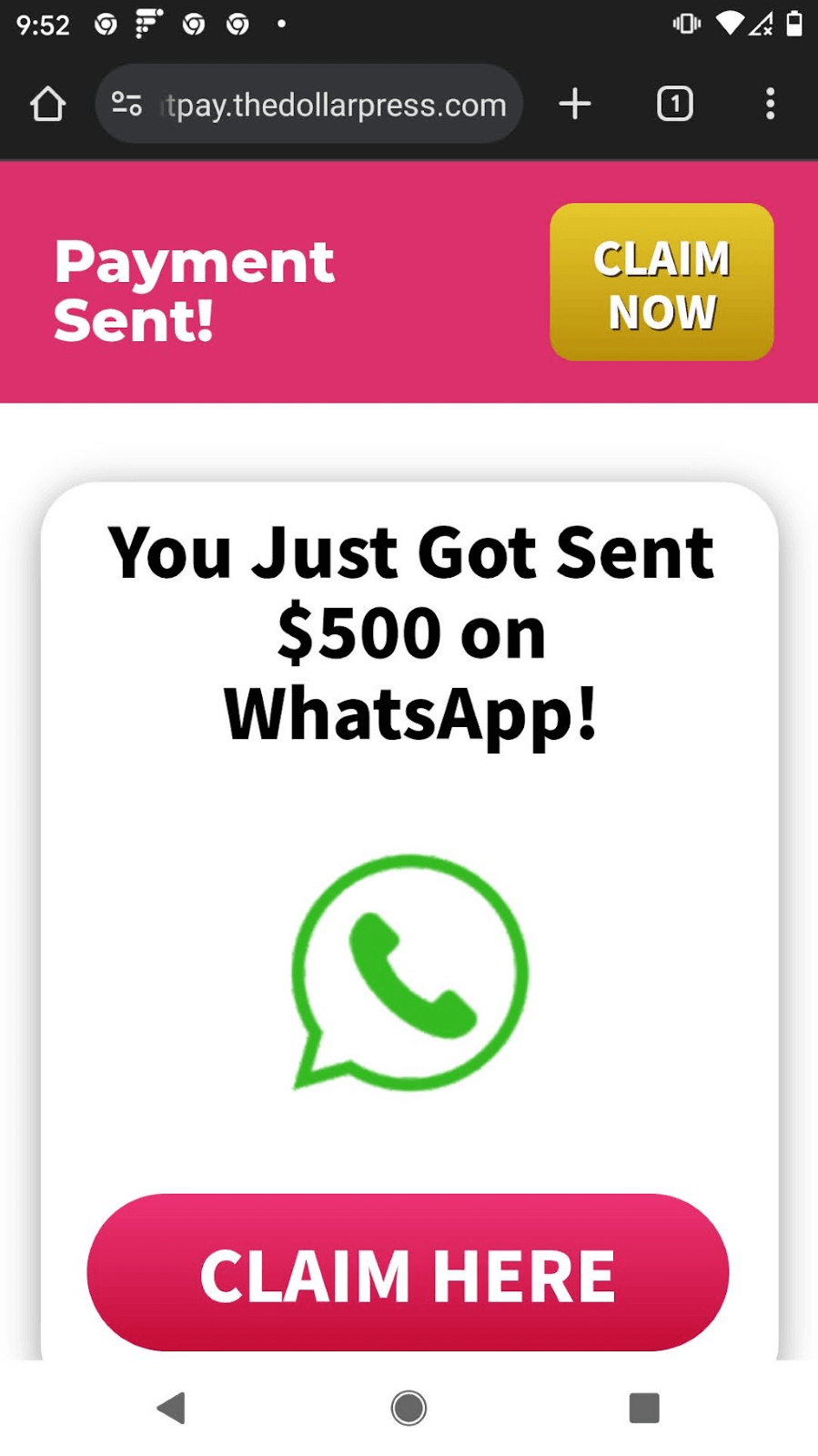

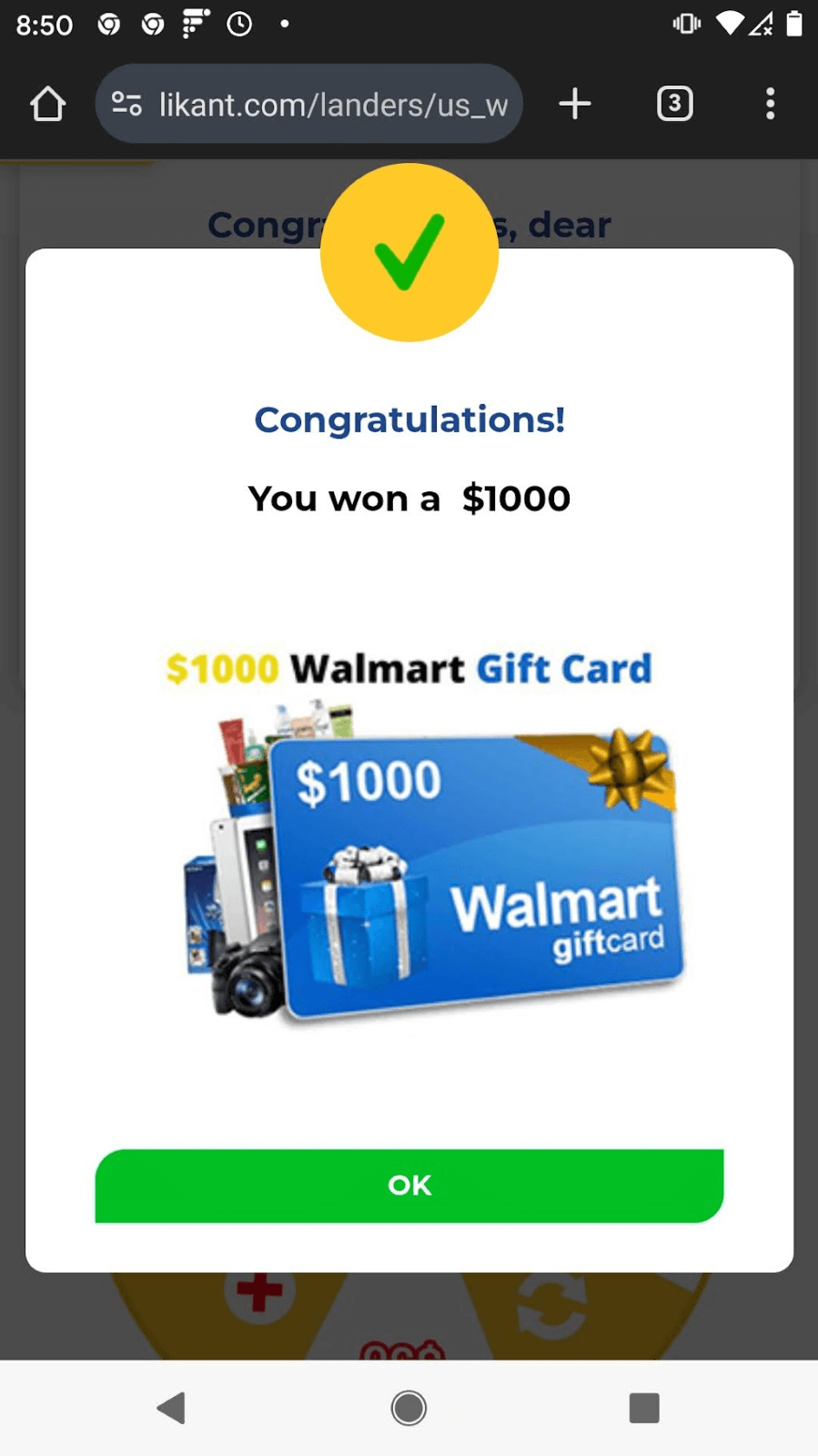

Often the push notification message doesn’t match the website where you finally land: the notification message might say you’ve won $500, but when your browser shows the site, it may say you’ve won $100. This discrepancy is because the notification “creative” is done by a different person than the fake reward site. The shady adtech world has cleverly divided the path from push notification to content so that different components are isolated from one another. The person who creates the message, like the ones seen in Figure 2, has no idea what the user will see in the browser. Similarly, when the user lands at a site like the one shown in Figure 2, the creator of that site is typically not connected to the push notifications. Adtech companies act as intermediaries and operate the TDS that routes victims to content.

Figure 2. Example of gift card or prize landing site. The video for the first image is found here: https://imgur.com/a/T5Tk1qz

To claim your gift card, you’ll need to provide personal information, like your email and home address. In some cases, you’ll have to take a “spin” to see if you’ve won the prize. Inevitably, within a few tries, the site will congratulate you on your win. Now you move into phase 2 of the scam: the survey. Regardless of what you do at this point, you will never get that gift card. Instead, you’ll be driven into an endless series of questions which lead to more and more ads.

The Survey Scam

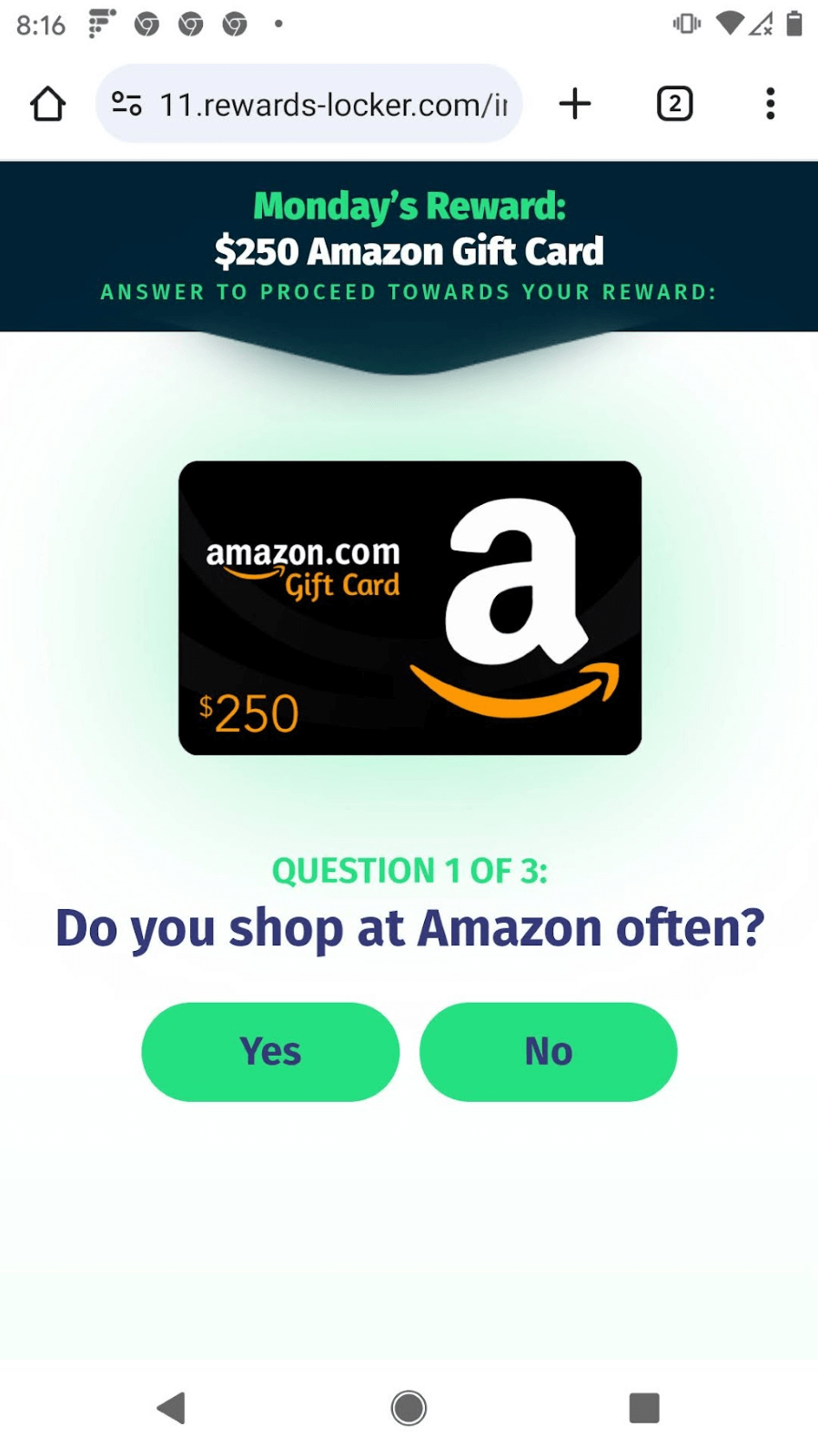

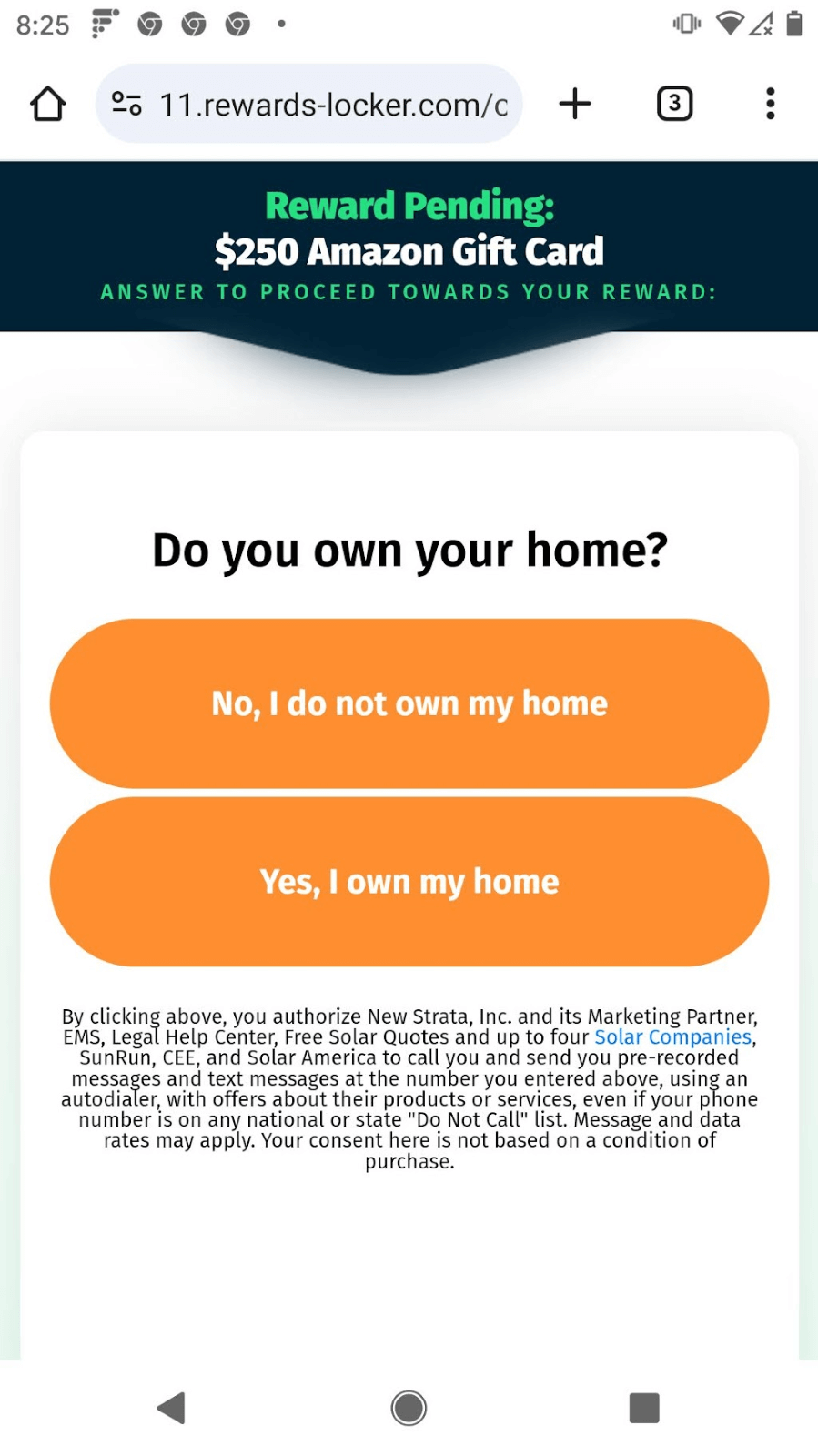

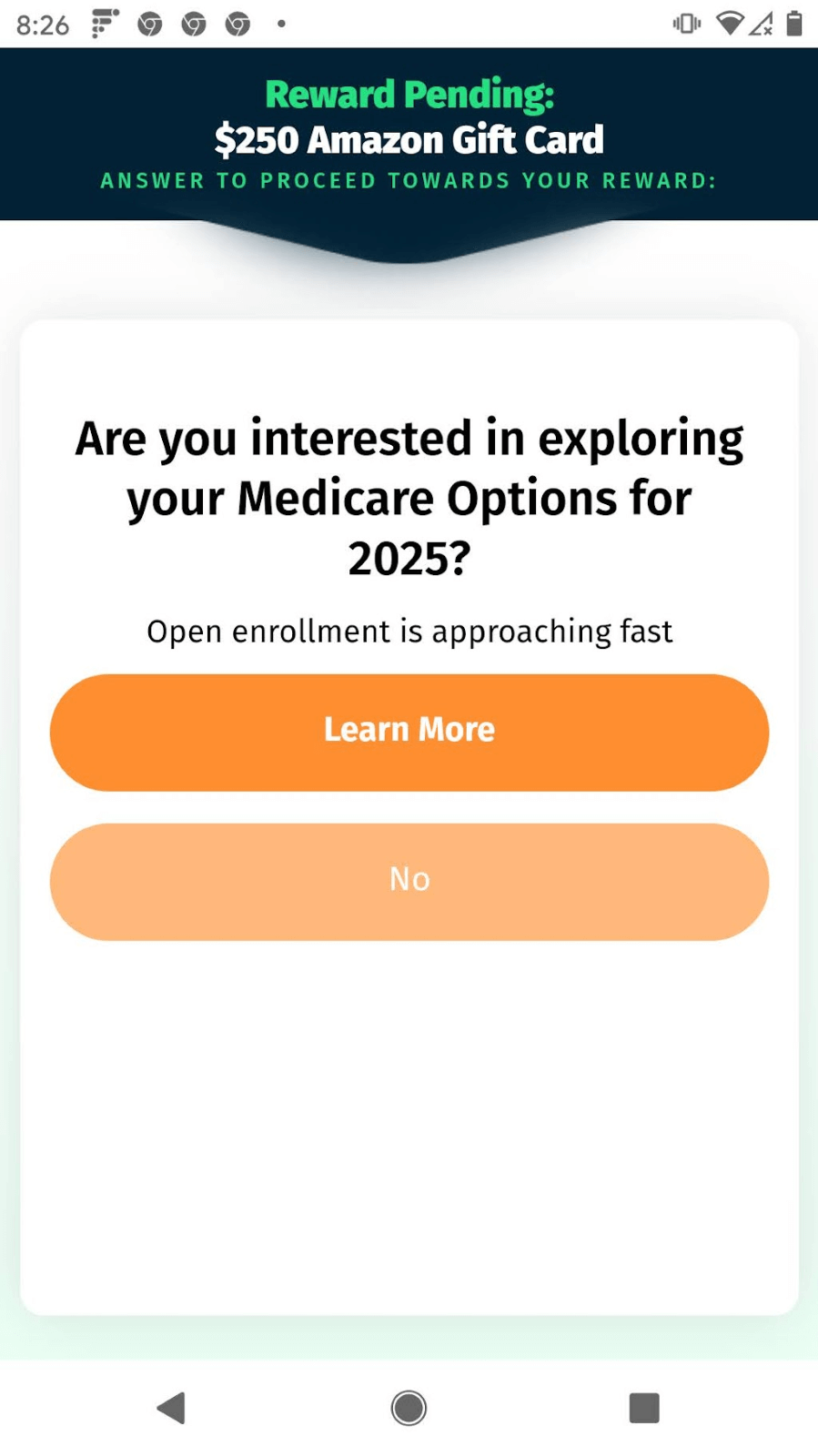

Consider what happened when I clicked on a notification alerting me that I had won a US$500 gift card from Amazon. After several redirections through different domain names, I ended up at the reward-locker[.]com webpage shown in Figure 3. My prize had gone from $500 to $250, and I hadn’t even started! To claim the gift card, I had to enter my email address, name, physical address and phone number. None of these sites check information, so you can put in whatever you like and continue to play their game. The secret here is that I had completed what adtech companies call an “action”—given my personal information to the website—and a variety of people get paid a few cents for this kind of milestone. The action and payment can vary wildly, with credit card submissions paying much more. I’ve seen advertising offers that pay $30 to obtain a user’s credit card number.

But giving over personal information is not enough. At this point, reward-locker[.]com must pay the adtech company for the successful advertisement and they want to make their money back! They do that by continuing to con the user. To receive my $250 Amazon gift card, I still needed to answer survey questions, like the ones shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The survey scam. Example screenshots of questions asked in order to proceed to a gift card reward. Answering any question will lead to an advertisement.

So… how does the scam work? Well, first of all, as I mentioned earlier, you’re never going to get that gift card. The questions never end. I have answered over 20 minutes of survey questions without getting to the final reward. Each time you answer a question one of three things might happen:

- A legitimate advertisement is shown

- You receive another scam and begin again down the rabbit hole toward your prize

- You move on to the next question

Every time I view a legitimate ad, reward-locker[.]com gets paid. I’m no expert in the advertising business, but based on the research I’ve done, they would probably receive about $0.05 on average. It’s not much, but there are economies of scale at work here: in promoting their services among affiliates, malicious adtech companies claim to make billions of impressions a day on users worldwide. The longer they keep me on the hook hoping for the Amazon gift card, the more they earn.

Sending me to another scam site might end up paying reward-locker[.]com even more. In that case, I inevitably had to enter personal data—completing another advertising “action” —which pays more than ad impressions. In that session, I was sent from Reward Locker to:

- bestdayeversweeps[.]com, which took my personal info, asked to show notifications and started another survey scam and eventually led me to:

- sweepstakealerts[.]com, which took my personal info, asked to show notifications and started another survey scam and eventually led me to:

- Yet more sites that took personal information and asked to show notifications

- sweepstakealerts[.]com, which took my personal info, asked to show notifications and started another survey scam and eventually led me to:

Eventually I got bored and gave up. But I played this same game dozens of times over the weeks that followed. Never did I get to the point of receiving a gift card, a cash refund or any of the many other things the original push notification offered.

Scammers use their affiliation with large ad networks, like Google AdSense and taboola, to deliver legitimate ads to users. In these cases, the advertiser will be unaware that their advertisements are being shown in a scam. In one case, after answering a question about protecting United States borders, I was shown an ad for the U.S. Navy. When asked about being abused by elders in the Mormon church, I was led to a class action lawsuit for victims from a law firm. I also received several advertisements for the church. See Figure 4 for some of the legitimate ads I saw from surveys. I asked colleagues at Confiant previously whether the U.S. Navy and others were aware where their advertisements show up? No. And I am certain that the Church of Latter-Day Saints (LDS) would be dismayed to learn how often a scam or gambling site led to them.

Figure 4. Examples of legitimate ads seen through survey scams.

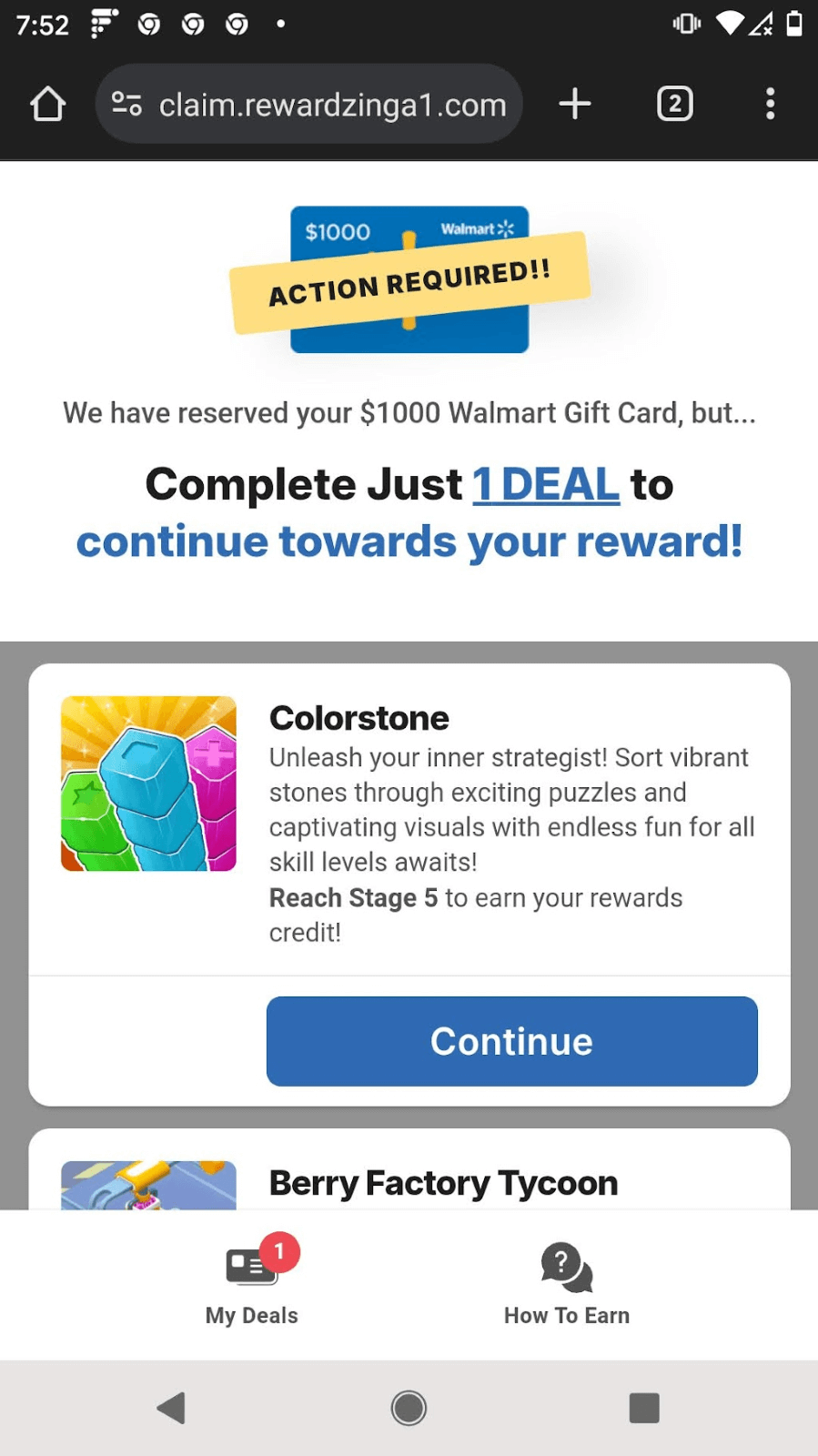

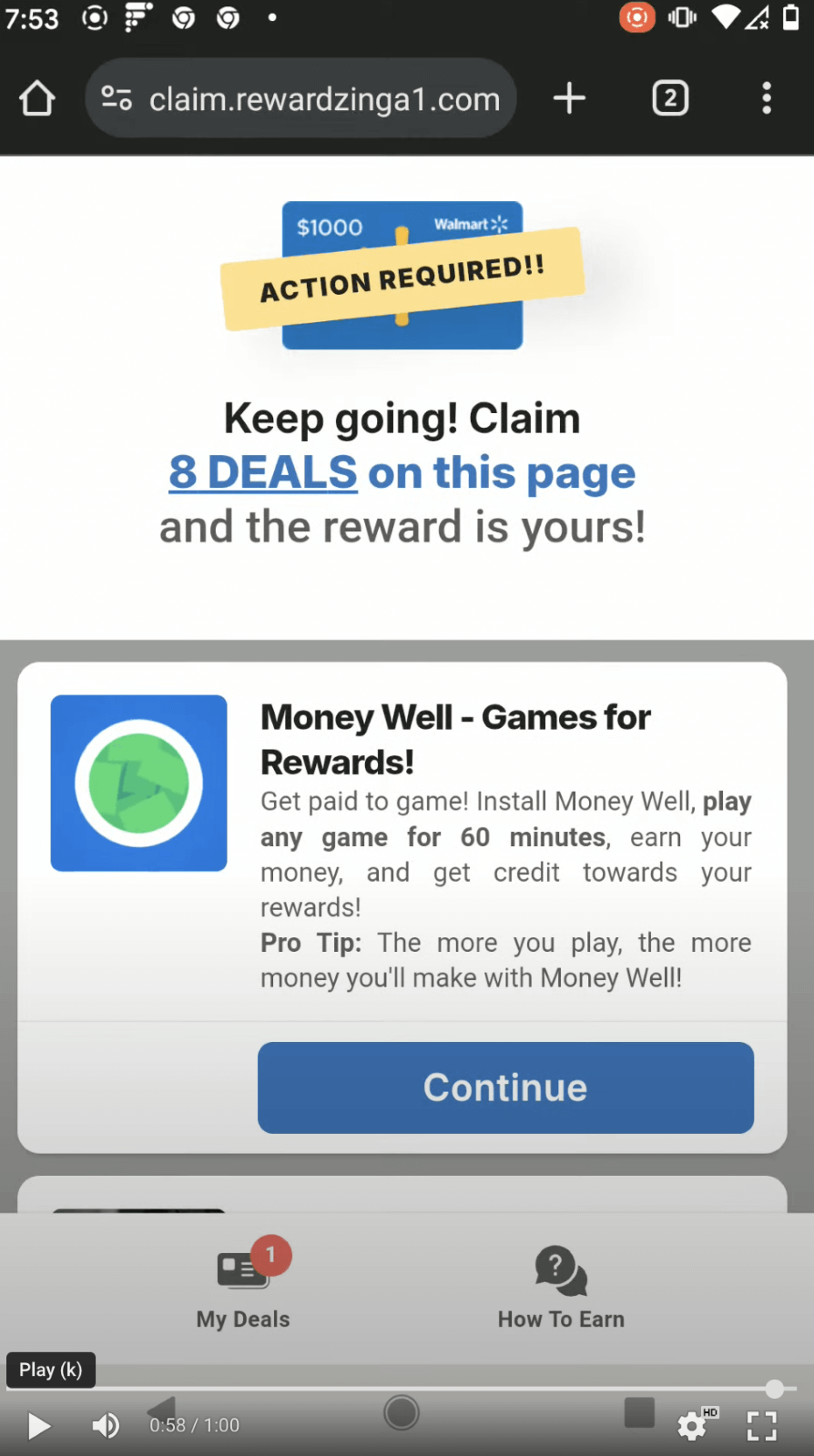

In most cases, I was roped into an endless trail of survey questions and advertisements with no end in sight. In a few instances though, after spending lots of time on the survey, I was told that in order to proceed “toward” my reward, I had to complete one task within a set of options. The options included downloading specific software, signing up for certain services or a number of other shady things I absolutely did not want to do. When I tried to skip this step, they bumped up the number of required tasks! Where I originally had to complete one task, I later had to complete eight in order to claim my gift card. See Figures 5a and 5b, and this video for examples.

Figures 5a and 5b. The rewardzinga1[.]com gift card scam required me to complete specific tasks to receive my reward. When I tried to skip the requirement shown in (a), the number of tasks increased as shown in (b).

Speaking of surveys, let’s talk about the sister scam: Sweepstakes.

Sweepstakes Scams

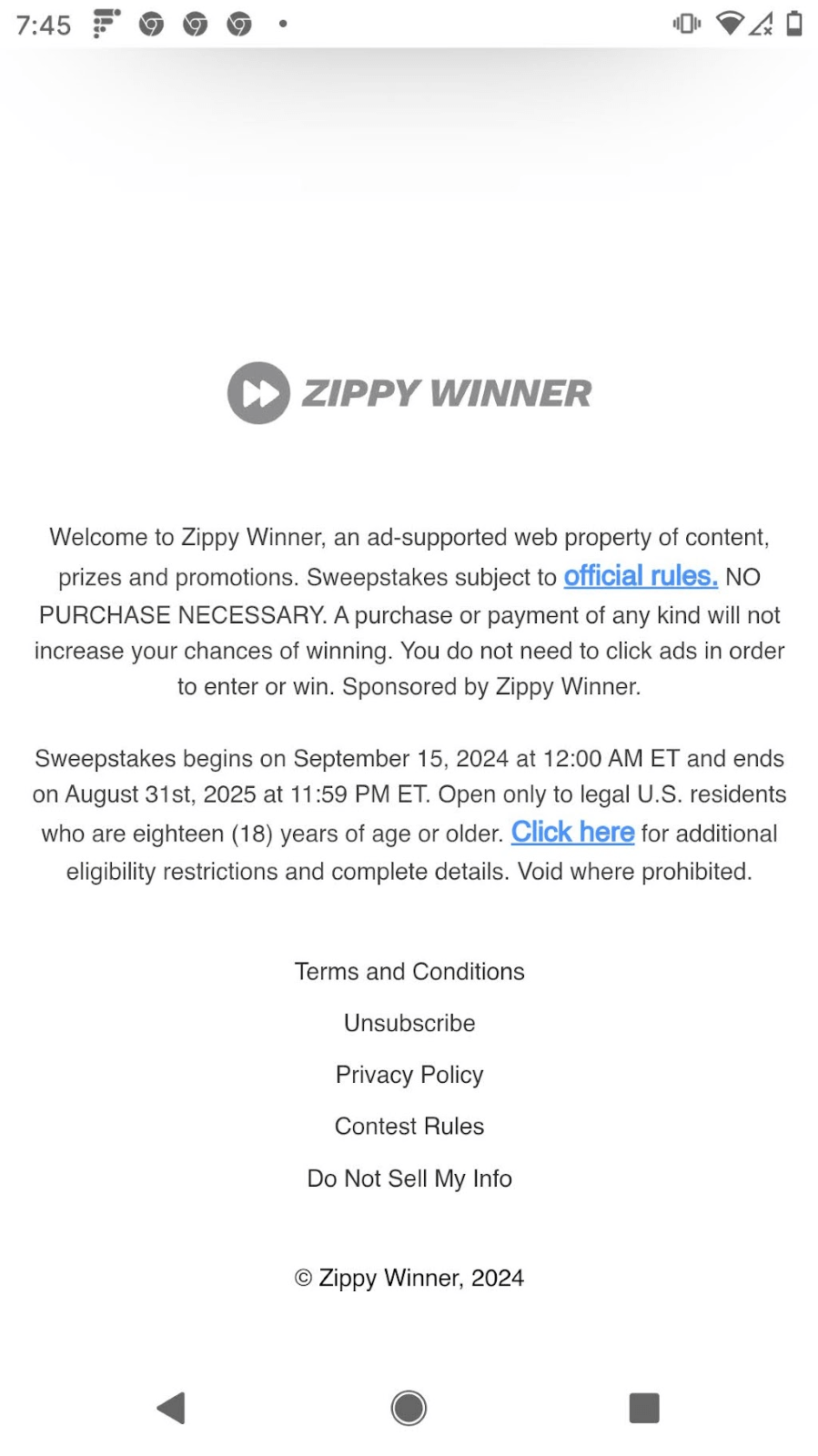

Sweepstakes are another common scam delivered via push notifications. These scammers often adorn their website with lots of legal language. I am sure that helps keep them out of the reach of law enforcement, but it is not hard to demonstrate their deception.

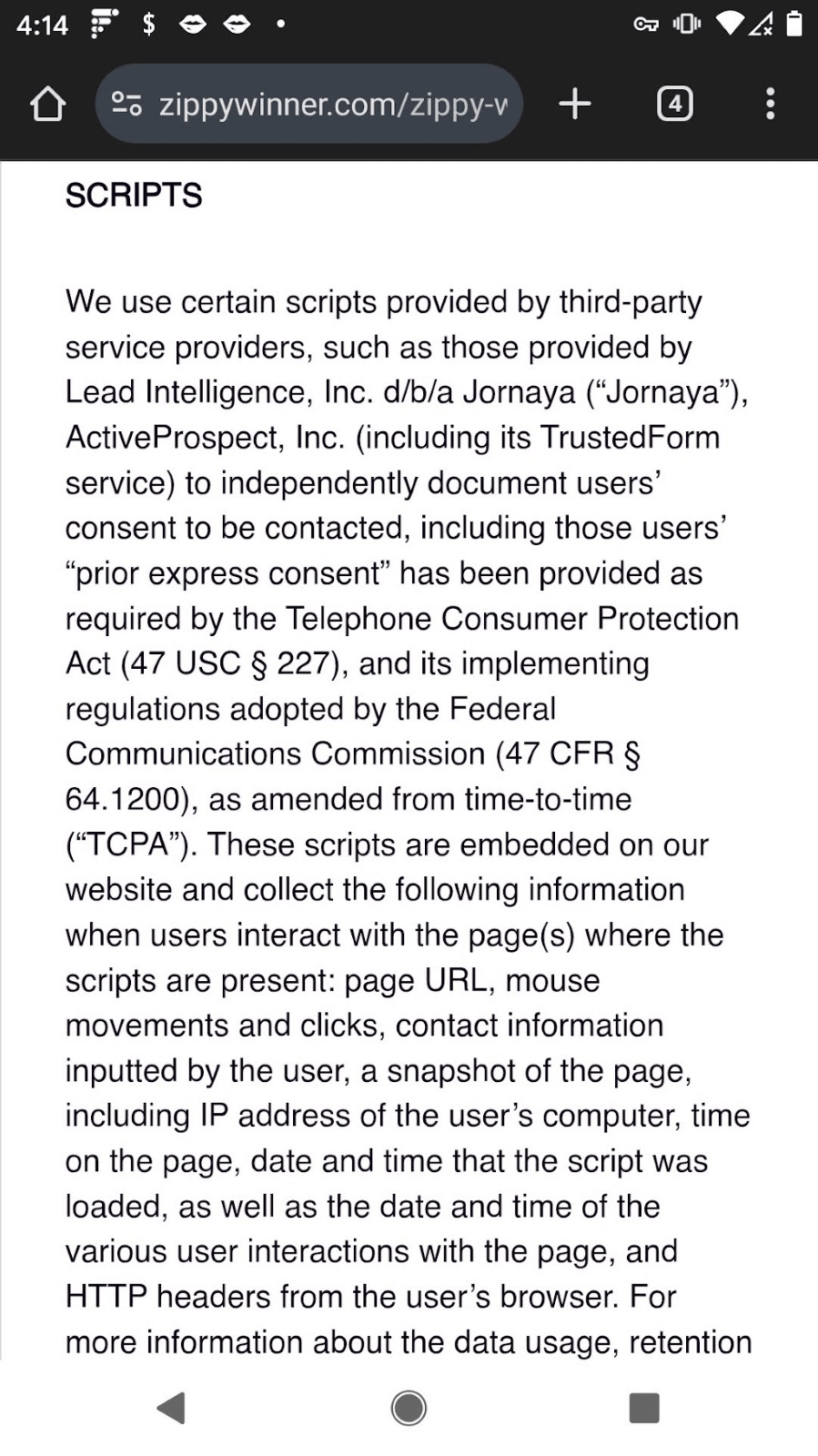

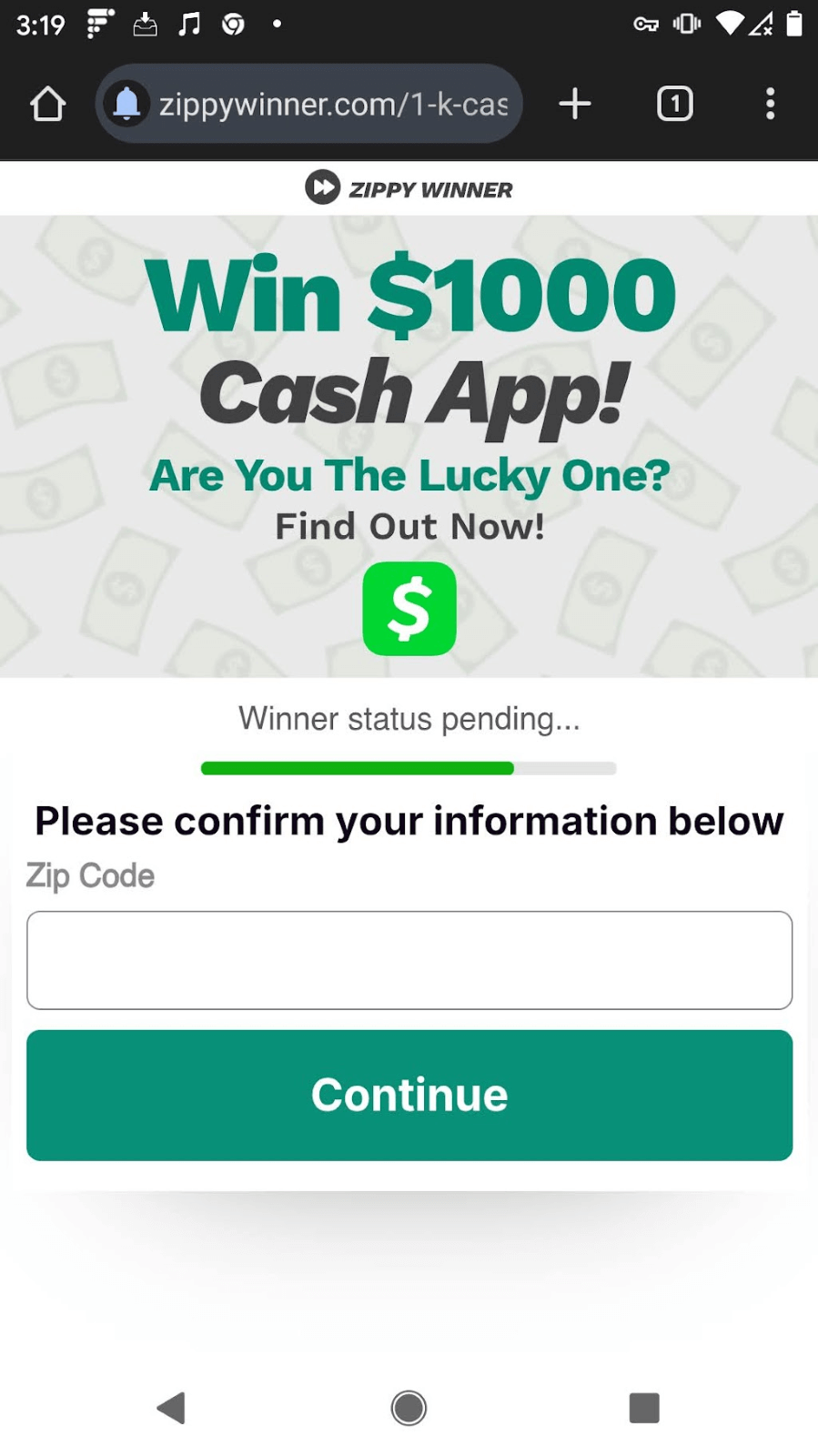

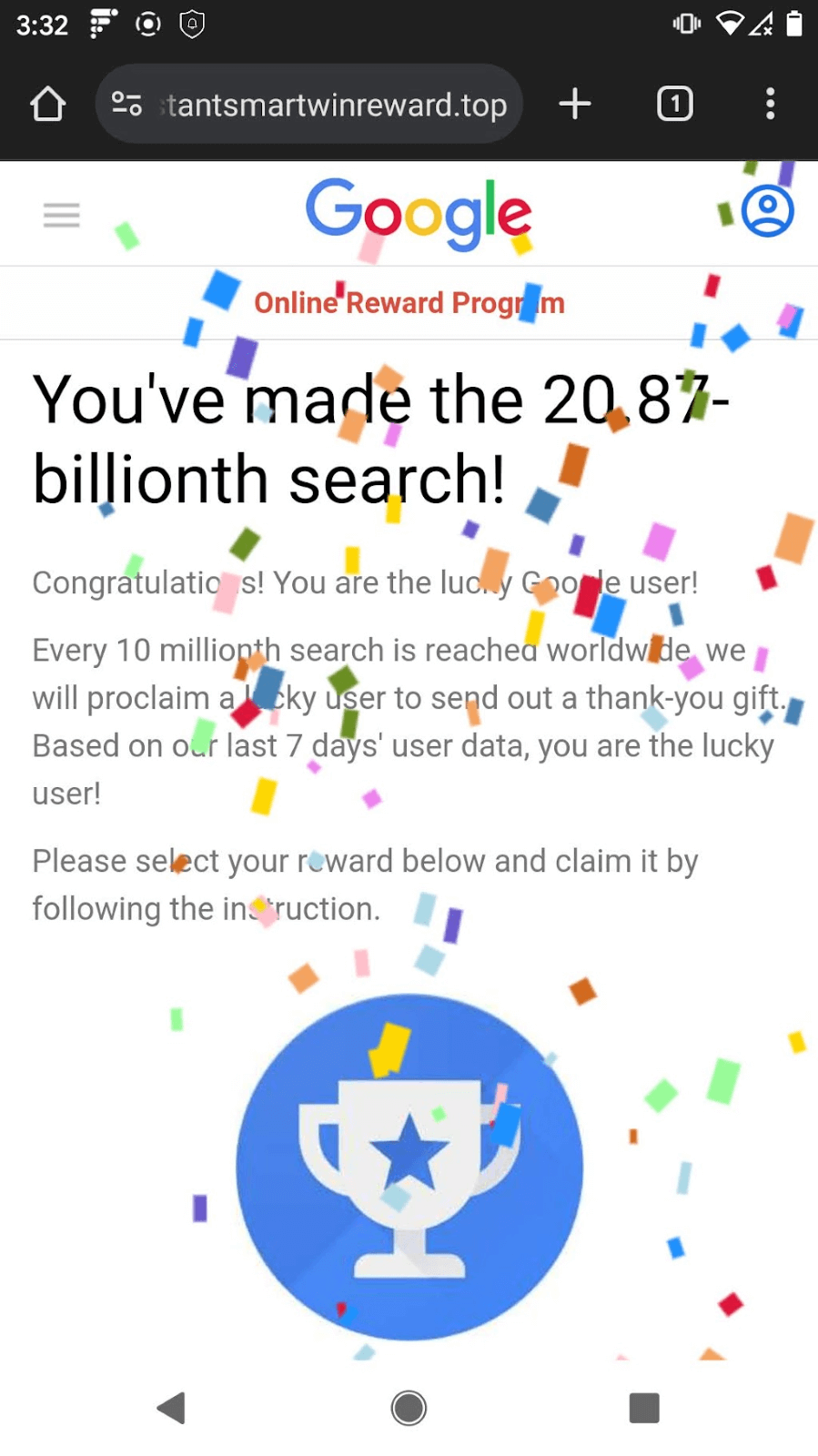

Take for example, zippywinner[.]com. For their sweepstakes, they offer similar legalese to all the other sites, as shown in Figures 6a and 6b. Their privacy policy includes the collection of a wide range of personal data, some of which is gathered through user entry and some via scripts embedded in their website. A push notification from Zippy Winner is shown in Figure 6c. Every “winner” notification from Zippy Winner led to surveys or additional sweepstakes when I opened the link; never to a real prize.

Figures 6a-6c. Zippy Winner’s site incorporates extensive legal documentation that includes their collection of personal information, such as biometric data, from their site.

The sweepstakes scam takes advantage of the common love of games and people’s eagerness to win random prizes. While there are differences among the sites, they are all set up to ensure the sweepstakes site pays little to no money to users. Here’s how they accomplish that:

- The sites all have a period for the sweepstakes. Frequently this is a year. During this time, users can “enter to win” and random numbers will be drawn at the end of the period. The site claims they will pay out if a user entry matches the drawn number, like a standard lottery.

- Many sites, like Zippy Winner, have extremely limited prizes. According to their rules, Zippy Winner will pay a total of 14 prizes during the year: 13 at $250 and one at $1,000.

- These sites include some other conditions that make the likelihood of winning very rare. Zippy Winner supposedly picks 14 moments in time during the contest. The first contestant who plays a “spin to win” game after each chosen moment in time becomes eligible to win.

- Any winner must then submit biometric data, to include a government-issued identification card, within three days. Anyone who does not meet their validation criteria will not receive their prize. All of the information, except the identification, is theirs to share with other parties.

Of course, Zippy Winner is not alone. There are an endless number of sweepstakes sites. Many of them lead the “winner” directly into a survey scam, which itself may lead to another sweepstakes. Some of the sweepstakes scam sites I visited include:

- bestdayeversweeps[.]com

- sweepstakealerts[.]com

- sweepchamp[.]com

- lucky7sweeps[.]com

- everydaywinner[.]com

- scratchstakes[.]com

- myamericanprzs[.]com

- blissxo[.]com

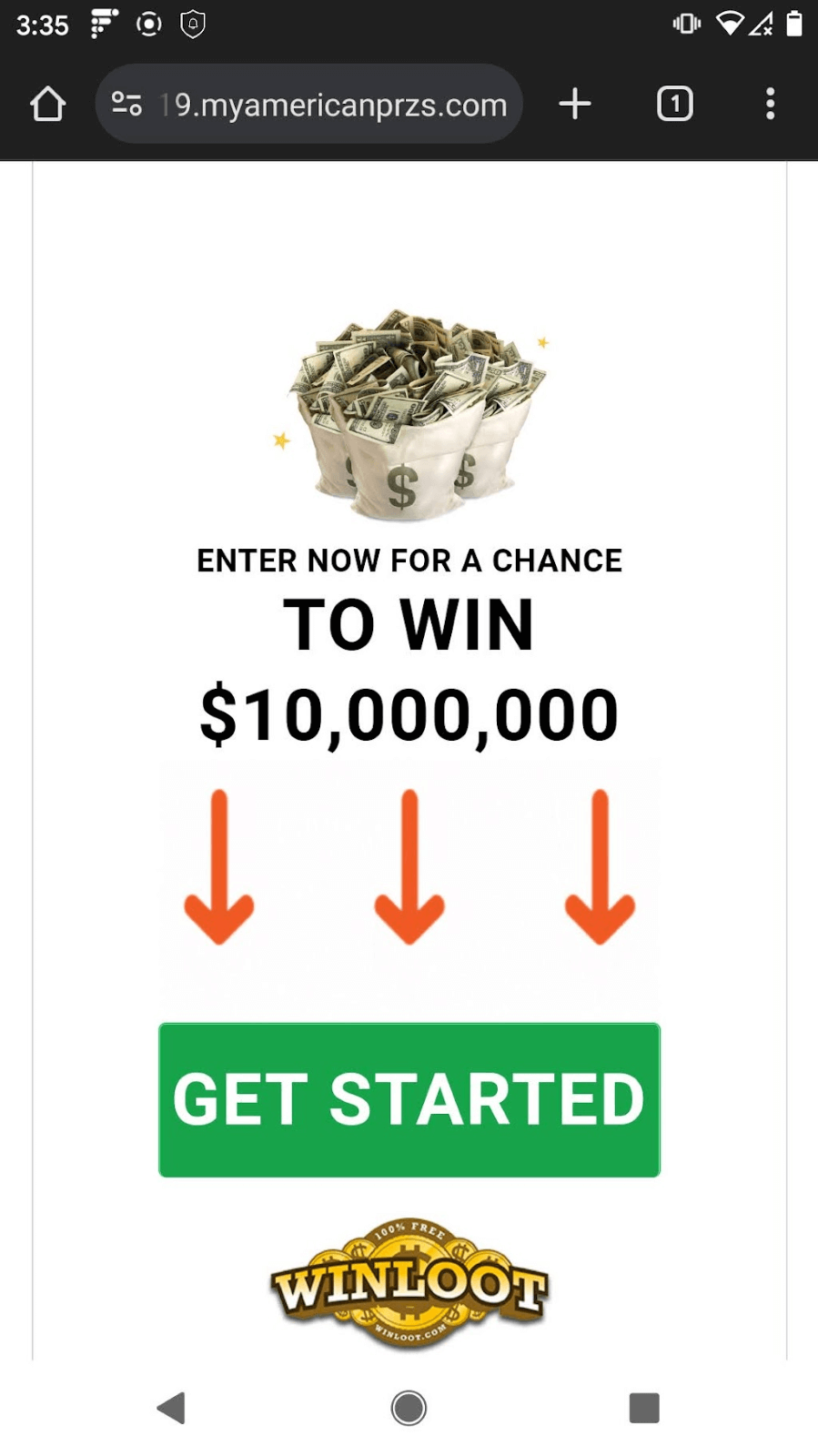

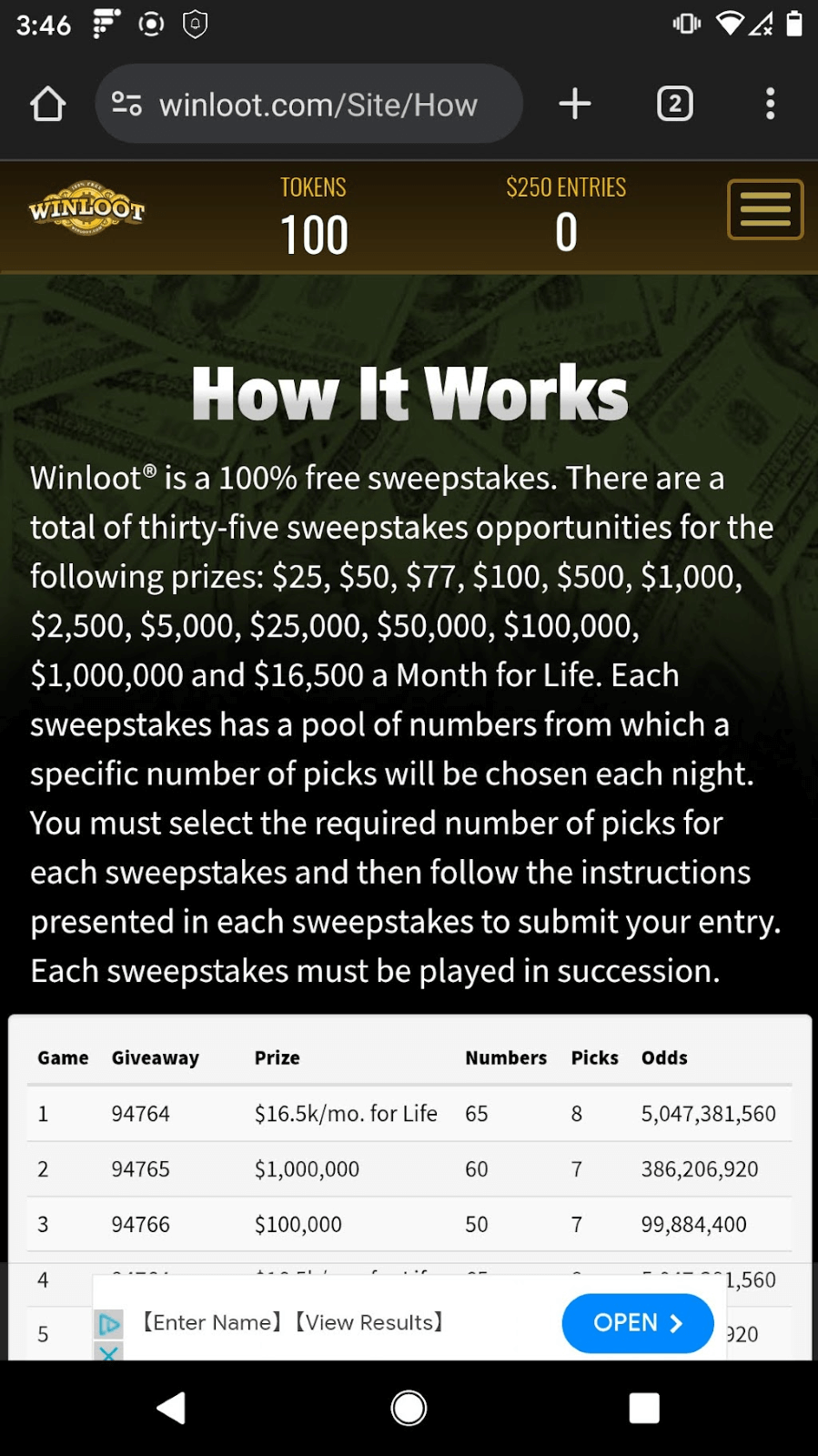

Because the sweepstakes and survey sites often advertise each other, it can be very difficult for the user to determine which are legitimate. From public reporting, for example, the company Win Loot (winloot[.]com) has paid out substantial prizes to players.1 In my own experience, though, I arrived at their website through a maze of scam sites which started with a deceptive push notification and went through multiple survey scams (see Figure 7). The Win Loot site is almost indistinguishable from Zippy Winner or the others listed above, except for the fact that it didn’t lead to a survey, and they gave clear odds of winning. The Win Loot website is plastered with misleading advertisements that cover up much of the screen. Many of these advertisements lead back to one of the survey scams listed above. I found this all pretty challenging to navigate and imagine the same is true for most users.

Figure 7. Selected sites on a path from a deceptive push notification to the Win Loot website. Along the way were multiple survey scams.

One closing thought. Many would argue that gift card, survey and sweepstakes scams are petty crimes by grifters. In some cases, the victim loses only their time to useless advertisements. Seems like a small issue, but is it? This vertical within the affiliate advertising industry cons users into giving detailed personal information, uses deception to obtain credit card information and pollutes the stream of advertisements and news they see outside of the scam sites. The only winners of this game are the scammers.