Author: Maël Le Touz and John Wòjcik

After uncovering Vigorish Viper in June of 2024, we kept following the DNS trail and have discovered dozens of other actors involved in illegal activities in Southeast Asia. While we spend our days knee-deep in domains related to these threats, there is a rich human story behind the scenes. This blog provides a sneak peek of what we’ve learnt about the ecosystem surrounding illegal gambling in the region over the past 18 months.

Background

Chinese-speaking criminal groups have been involved in gambling and the drug trade for decades, and have long had a footprint in Southeast Asia. In recent years, however, they have rapidly scaled up their involvement in cyber-enabled fraud, generating tens of billions of dollars in financial losses for victims around the world. In the United States alone, authorities reported more than USD $5.6 billion in financial losses to cryptocurrency scams in 2023, with an estimated USD $4.4 billion attributed to so-called “pig butchering” schemes most prevalent in Southeast Asia.1 Regionally, countries in East and Southeast Asia combined have lost up to an estimated USD $37 billion to cyber-enabled fraud during that same year, according to latest available data, with much larger estimated losses being reported globally.2

Powerful criminal groups based out of Southeast Asia have quietly taken control of some of the most vulnerable parts of the region to conduct these industrial-scale operations, infiltrating or even establishing so-called Special Economic Zones (SEZs). In recent years, it has become clear that many of the region’s SEZs, alongside casinos, hotels, and other business parks and property developments infiltrated by Asian crime syndicates, have evolved into sprawling citadels of organized crime—lawless enclaves where scam centers, modern slavery, and illicit finance converge under the veneer of legitimate development.

These zones, often touted as engines of economic growth, have emerged as fortress-like strongholds for sophisticated transnational Asian crime syndicates, complete with their own armed security, entertainment, criminal service providers, and more. Within their walls, entire industries of exploitation thrive: human trafficking pipelines feed captive workforces, high-tech fraud operations siphon billions from victims worldwide, blurring the boundaries between state authority and criminal enterprise while fundamentally reshaping the regional cyberthreat landscape.

As these criminal enclaves continue to expand, investigators face steep challenges in disrupting them, thanks to fraud schemes like pig butchering and the fluid, decentralized networks behind them designed to evade detection at every level. This has not only allowed pig butchering to thrive in the blind spots of traditional threat hunting methods, but has allowed these operations to adapt and deliver fraud content at scale with remarkable speed.

Schemes like pig butchering leave an unusually faint digital footprint: a single fraudulent website can be enough to siphon millions of dollars, and most victim outreach occurs through private messaging platforms, generating little public evidence to track. At the same time, while individual scams may not require deep technical sophistication, executing them at scale does—demanding robust backend infrastructure and a broader criminal service ecosystem to identify and social engineer targets, sustain deception campaigns, streamline technical workflows, and launder vast volumes of illicit funds.

In light of this, rather than listing domain names or crypto wallets, the below analysis serves as an introduction to a series of short releases focusing on pig butchering scams originating from Asia, highlighting how DNS can be used to track the criminal networks responsible and map out parts of their online infrastructure.

Using this approach, we examine scam campaigns originating from two infamous compounds—Laos’ Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone (GTSEZ) and Myanmar’s KK Park—and offer insights into a recent high-profile case currently being prosecuted in the United States. In doing so, we also describe the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) the scammers have used to dupe their victims and set up their infrastructure.

In both cases examined below, Infoblox has detected hundreds of near-identical websites registered and deployed by the criminals. That said, the criminal networks behind those campaigns remain active and continue to attract potential victims via social media and registration of new domains.

What Is Pig Butchering?

Pig butchering, known in Chinese as “Shā Zhū Pán” (杀猪盘) is a prolonged investment fraud or long-con where criminals entice victims into depositing ever-larger sums into sham platforms and accounts, frequently tied to cryptocurrencies. It first took root in countries of East and Southeast Asia, where criminal groups have a long history of running sophisticated organized fraud operations. The term describes the process of “fattening up” victims with trust and false promises before ultimately “slaughtering” their savings. Here’s how the scheme typically unfolds:

- Scammers initiate contact with victims through dating apps, social media platforms, or private messaging services like WhatsApp. Relationships between scammers and victims may include friendship, romance, or investment mentorship.

- After establishing rapport, they steer the conversation toward supposed investment opportunities as well as other schemes, including fake job offers or task scams, often tied to cryptocurrency markets.

- Victims are gradually persuaded to commit ever larger sums into fraudulent platforms which display huge profits, only to see everything vanish once the criminals get a sense that the victim has deposited everything they can and abscond.

Central to the scam is psychological manipulation: perpetrators cultivate emotional bonds, instill confidence, and in some cases even simulate romantic relationships. This drawn-out grooming process lowers victims’ defenses and primes them to believe in promises of extraordinary returns, leading to devastating financial losses.

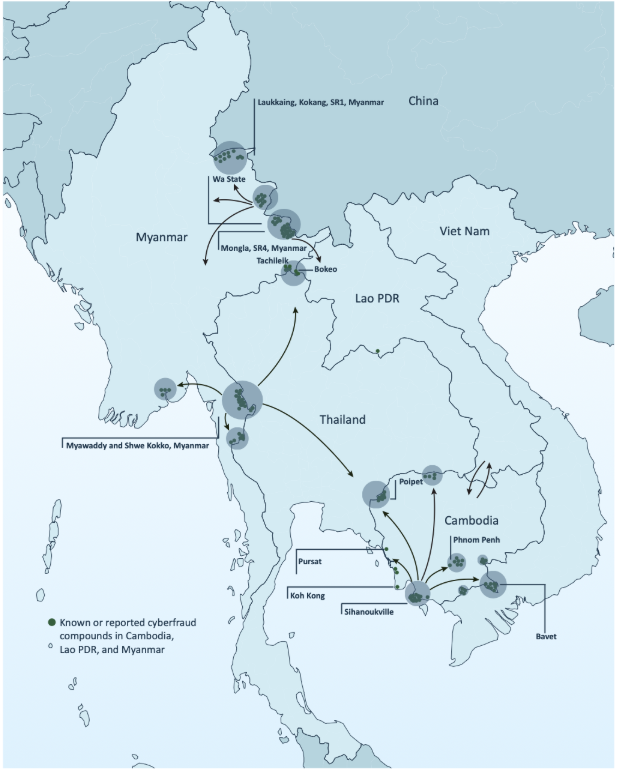

These schemes are predominantly run out of criminally controlled areas scattered across Southeast Asia, particularly congregating around SEZs such as the GTSEZ (see Figure 1 below) which have been established in vulnerable borderlands and militia-controlled territories where thousands of people have been lured and forced to scam. See Figure 2.

Figure 1. The GTSEZ, an entire city dedicated to criminal activity, leisure and entertainment (UNODC, 2024)

Figure 2. Locations of known or reported scam centers in the Mekong region, 2023 – 2025 (UNODC, 2025)

Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone

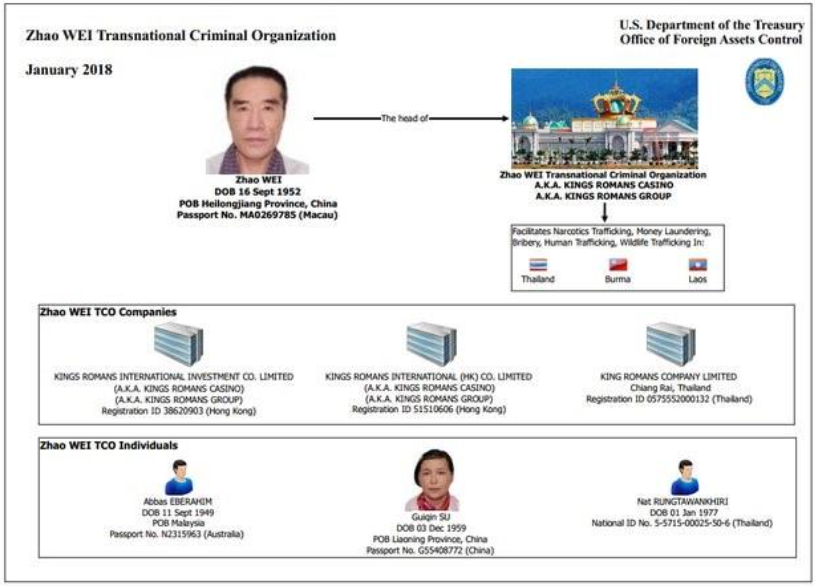

Representing one of the most prolific cyber-enabled fraud hubs in Southeast Asia, the GTSEZ is a 3,000-hectare zone in Laos located at the border with Thailand and Myanmar (listed as Bokeo in Figure 2). In 2007, the Kings Romans Group was awarded a special 99-year lease by the Laos government to develop the zone. However, the area is de facto under the control of senior triad leader Zhao Wei (赵伟), who is currently subject to U.S. treasury sanctions (see Figure 3), accused of crimes including money laundering, child sexual abuse, as well as human, drug, and wildlife trafficking. For good measure, in 2023, Zhao announced the launch of his own airport while also securing concessions for three islands off the coast of neighboring Cambodia’s infamous crime hub, Sihanoukville, using his newly acquired Cambodian citizenship.3,4

Figure 3. Zhao Wei Transnational Criminal Organization (OFAC, 2018)

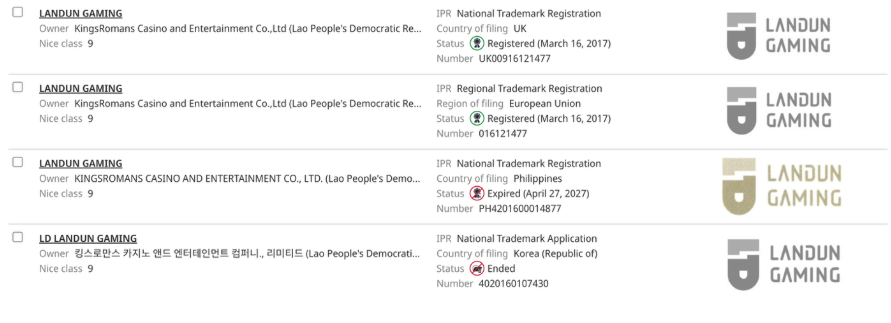

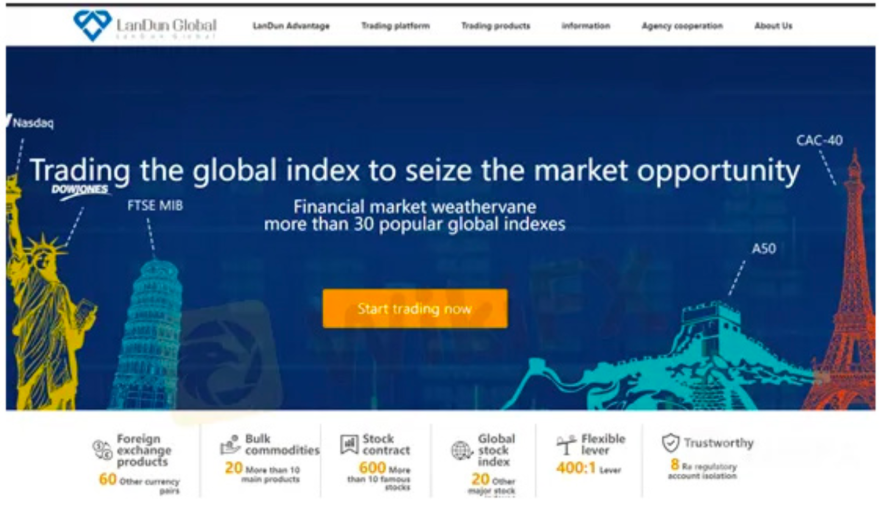

Zhao has incorporated dozens of companies and has links to an extensive network of shell companies around the world. Among his greatest operational security (OpSec) fails, however, has been his Landun or Blue Shield brand, which relates to the group’s land-based casino, online gambling, logistics, transportation, property development, and investment portfolios. In reality, the criminal conglomerate runs diversified money laundering, underground banking, and cyber-enabled fraud operations, which operate internationally on an industrial scale. This is most apparent through examination of Kings Romans’ Landun Gaming trademark, which was recently tied to a significant pig butchering scheme reported by the Taiwanese police and UNODC (see Figures 4, 5, and 6).5,6

Figure 4. Intellectual property corresponding to Landun Gaming registered by Kings Romans Casino and Entertainment Co. Ltd in various jurisdictions, 2025

Figure 5. Screenshot of Landun Global Investment platform reported by victims of online fraud, 2025

Figure 6. Taiwan National Police Cyber-Enabled Fraud dashboard, which lists pig butchering-related domains and corresponding investment platforms, the majority of which have also been identified by our research as malicious (2025)

Using these starting points, we were able to trace one of the fraudulent Landun Investment websites reported by multiple fraud victims back to a cluster of hundreds of similar pig butchering domains pushing a mix of fraudulent foreign exchange, crypto investment, wealth management, and online gambling platforms.

While the network tried to use public cloud proxies and hosting, hoping to obfuscate their trail and hide in the sea of legitimate traffic, they did not excel at covering their online tracks. That said, they have now switched to using Cloudflare. The scam domains they operate are briefly hosted on specific IPs before being shielded by the Cloudflare proxy, which is consistent across different campaigns. This unique pattern allowed our researchers to detect dozens of websites through passive DNS (pDNS), tying back to websites linked to numerous Hong Kong and UK front companies registered at PO boxes and incorporated by Chinese nominees. Addresses used by the only two UK-registered Landun entities in existence trace back to PO boxes that have been used as domiciles for more than 13,000 companies in total. The majority of those companies are linked to widespread complaints and warnings issued by authorities and victims alike, with several tracing back to our cluster.

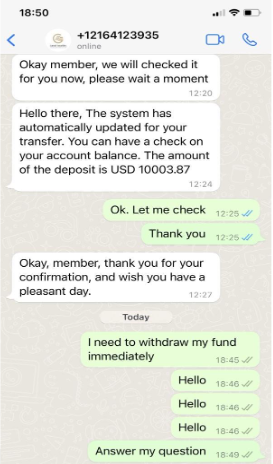

One entity relates to Carrod Securities Co Ltd, which has been widely reported by fraud victims online and formally implicated as part of a high-profile pig butchering case in Delaware (Figures 7 and 8).7 Victims of the trading platform described a typical pig butchering scheme whereby they were encouraged to continue increasing their initial investments until finally attempting to withdraw their apparent profits. Users would subsequently lose account access and all contact with platform administrators. Dozens of complaints online indicate that Carrod Securities targeted victims from Canada, Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States, among other countries. DNS records reveal upward of 350 unique domains are part of the broader fraud network. The same website template has been used by the cluster since at least 2017.

Figure 7. Screen capture of Carrod Securities’ fraudulent investment platform (Source: DomainTools)

Figure 8. Screen capture of text messages sent between Carrod Securities affiliate and online fraud victim shared, 2023

KK Park

Located near Myawaddy, on the Myanmar/Burmese border with Thailand, KK Park is an infamous scam and casino compound operated by a large Chinese-speaking criminal network linked to senior triad leader, Wan Kuok-Koi (尹國駒), better known as “Broken Tooth.”

Similar to the forced labor conditions found within many GTSEZ operations, the conditions within KK Park are reportedly among the worst in the region. Testimonies from survivors consistently describe 18-hour working days and rigid performance quotas. Victims are incentivized to meet their quotas through systematic public beatings, electrocution, as well as various forms of sexual violence and abuse.

The compound is secured by heavily armed local militia forces, surrounded by layers of barbed wire fences, monitored by CCTV surveillance, has bars on the dormitory windows, and the strictly enforced communication and mobility protocols prevent workers from contacting the outside world for help or coordinating escapes. Those who fail to comply suffer devastating consequences.

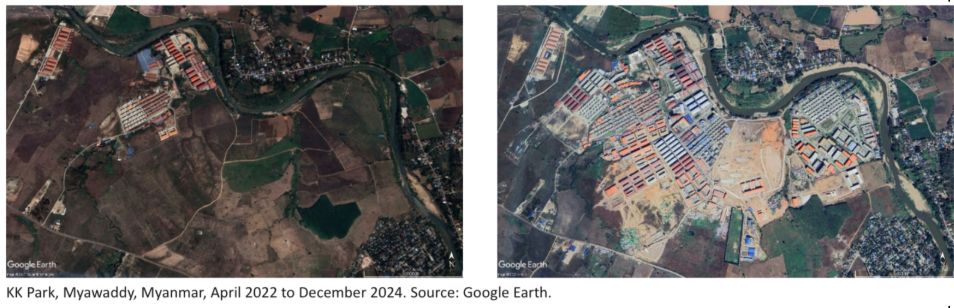

Despite years of international pressure from human rights groups and governments around the world—including power and internet cuts by neighboring Thailand, and U.S. sanctions related to billions of dollars in losses— the compounds have continued their rapid expansion, as shown in Figure 9. But what do these operations really look like online?

Figure 9. KK Park’s expansion over the last several years (Source: UNODC)

In a recent high-profile report by investigative journalists at Mizzima, a leading independent Myanmar media organization, investigators identified several pig butchering domains that we used as our starting point, attempting to replicate and build on their initial analysis, using our own data. Lo and behold, we quickly identified hundreds of identical websites dedicated to a robust network of online scams and money laundering at scale.

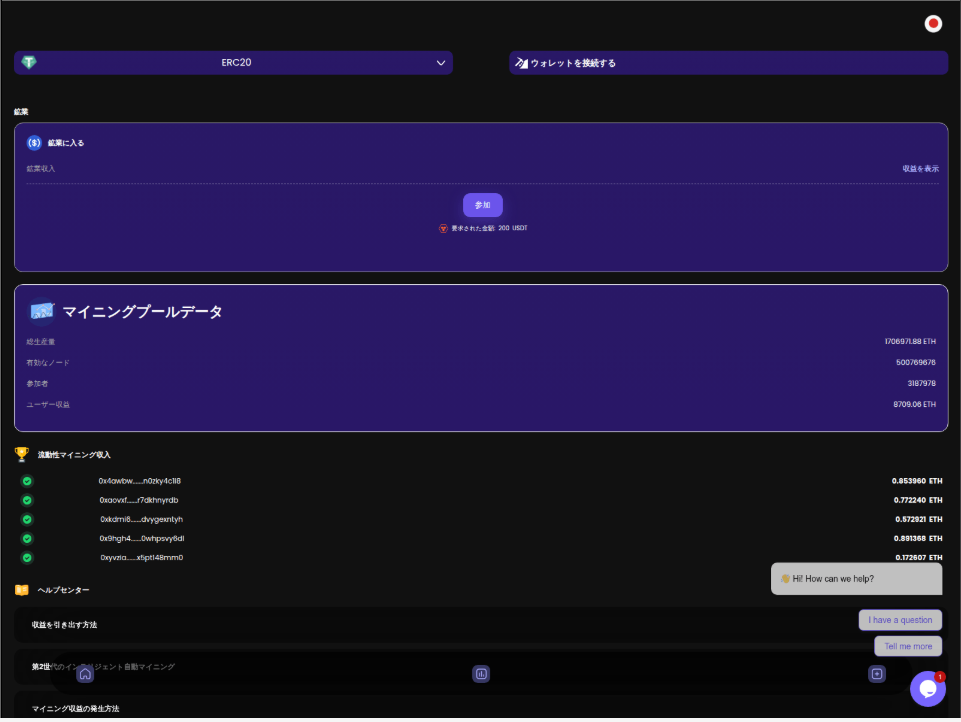

Due to the scammers reusing the same website templates (see Figures 10 and 11), Infoblox Threat Intel was able to identify hundreds of similar pig butchering domains, as with networks operating out of the GTSEZ. These domains all use the same code and naming patterns: only the default language and cryptocurrency wallet addresses change.

![Figure 10. Capture of ethmp[.]net mentioned in the Mizzima investigation](https://blogs.infoblox.com/wp-content/uploads/pig-butchering-scams-fig-10.png)

Figure 10. Capture of ethmp[.]net mentioned in the Mizzima investigation

Figure 11. Other variations of the ethmp template, using an AI chatbot for “customer” (victim) support

Making use of another significant OpSec fail, we were able to gain access to victim-facing pages containing rotating deposit wallet addresses used by the scammers. Coincidentally (not really) many of these addresses were also referenced by victims of human trafficking in connection to phishing and no-KYC (know your customer) crypto casinos, presumably utilized and integrated into the network’s operations for money laundering purposes. Their presence is not accidental. Systematically, the KK Park operators will launder the revenue from pig butchering through crypto casinos, including the Hash Bet 28 online casino as shown below in Figure 12.8

Figure 12. A gambling website used by KK Park to launder their crypto gains

These anonymous crypto casinos are a far cry from the sophisticated offerings of Vigorish Viper—only offering sports betting, live baccarat, scratch games, etc.—and are actually very crude. They are a simple way to clean, layer, and obscure the nature of dirty money without resorting to expensive third-party games, cleverly using the blockchain itself to determine random outcomes.

In this particular model, players deposit their “bets” anonymously into a given wallet and proceed to bet on the last digit of the next blockchain hash. Will it be even? Greater than five? And so forth. By way of a smart contract, a bot will analyze the results in real time to determine the winners and split the winnings. No player interaction is needed, and any losses are simply factored into the scammer’s cost of doing business. All one needs is a crypto wallet and some time. Since the odds are fixed, like roulette, the cost of laundering money is consistent and generally negligible.

The fraud network can systematically cycle their criminal proceeds through these platforms for hours—a process sometimes referred to as “chip dumping”—before ultimately cashing out or moving the funds further along the laundering chain. On sites that support multi-player gambling, scammers can also stage deliberate losses, transferring large portions of stolen funds to collaborating accounts under the guise of legitimate play. Together, these methods not only make victim funds far more difficult to trace, but also provide criminals with a ready-made cover story for their otherwise inexplicable wealth. When challenged, they can simply point to gambling “winnings”—a claim difficult to disprove given that these casinos are typically registered offshore, deliberately opaque, and rarely compliant with law enforcement requests.

Pig Butchering-as-a-Service

Unsurprisingly, the abovementioned examples both show strong signs of leveraging a pig butchering-as-a-service (PBaaS) model, through which online fraud operators can systematically push and deliver fraud content to targets at scale. While these types of operations will be explored in greater depth in a future article, the approach has supercharged the ongoing crisis, proving highly effective in providing criminal groups with the ability to lower costs and automate setup through ready-made infrastructure. This includes prebuilt scam websites, investment platforms, laundering methods, and scripted chat playbooks, as well as scalable targeting mechanisms that allow low-skill actors to reach large pools of victims with ease. Moreover, PBaaS has resulted in scam infrastructure becoming so cheap and replicable that a domain is treated as a single-use asset, rendering domain-by-domain blocking functionally obsolete.

By commoditizing the tools, narratives, and workflows of pig butchering and other related scams, these service providers have dramatically lowered the barriers to entry for would-be criminals and amplified the overall reach and persistence of the fraud ecosystem in and increasingly beyond Southeast Asia, warranting deeper examination of the networks behind them.

Conclusion and Future Trends

As highlighted throughout this article, pig butchering has exploded into an industrialized fraud economy generating tens of billions of dollars annually. Sophisticated Asian crime syndicates have proven adept at spinning up hundreds of disposable websites in minutes, overwhelming governments that cannot detect or block them fast enough to shield victims. Arrests and takedowns, when they happen at all, struggle to impact the stream of new domains and cloned platforms pushed out daily by syndicates operating from fortress-like compounds in the region. DNS has thus become a decisive battleground, with every scam domain, no matter how disposable, having to resolve in order to reach its victims. By identifying shared templates, resolution patterns, and network-level fingerprints, defenders and researchers alike can effectively disrupt thousands of scam domains at scale.

As highlighted in our case studies, domains traced back to Southeast Asia’s scam centers exhibit consistent reuse of hosting infrastructure and DNS configurations across fraudulent investment sites, allowing entire clusters of pig butchering domains to be efficiently flagged and potentially neutralized.

Footnotes

-

2023 Internet Crime Report, Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2023.

https://www.ic3.gov/annualreport/reports/2023_ic3report.pdf

-

Transnational Organized Crime and the Convergence of Cyber-Enabled Fraud, Underground Banking and Technological Innovation in Southeast Asia: A Shifting Threat Landscape, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), October 2024.

https://www.unodc.org/roseap/uploads/documents/Publications/2024/TOC_Convergence_Report_2024.pdf

- Casinos, Money Laundering, Underground Banking and Transnational Organized Crime in East and Southeast Asia: A Hidden and Accelerating Threat, UNODC, January 2024.

- Osiano Trading Sole Co., Media Release, 2022.

-

Taiwan National Police Agency, Ministry of Interior of Taiwan, Online Fraud Alert Bulletin, 灣警政署165防騙網111/7/18-111/7/24民眾通報假投資(博弈)詐騙網站.

https://165.npa.gov.tw/

- Transnational Organized Crime and the Convergence of Cyber-Enabled Fraud, Underground Banking and Technological Innovation in Southeast Asia: A Shifting Threat Landscape, UNODC.

-

Carrod Securities Co Ltd, mentioned in Investor Protection Matter Nos 21-0137, 220-119, 09/23/2022.

https://attorneygeneral.delaware.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/50/2022/10/Order-to-Cease-and-Desist-Crypto-PBS.pdf

-

Tron Scan, 2025. Accessed at:

https://tronscan.io/#/address/TMLQfHV1ChFtBNb55zD9soX9LSbtksKuUT