Executive Summary

Just how dangerous is a parked domain? A lot more than you might think. Defenders often associate parked domains with bland pages filled with search advertisements, leading many to conclude they are harmless. But the landscape has changed. Increasingly, the user is led directly to an “advertisement.” We use quotes here because an extensive investigation into the modern parking ecosystem found that the landing page was malicious more often than not. But it’s not just malicious advertisers that make parked domains risky; threat actors operating within the complex ecosystem abuse it in ways that make crime easy and attribution difficult. We’ve spent the last several months trying to untangle it. Along the way, we found actors pulling DNS shenanigans. This report describes why parking has become more dangerous and details three previously unpublished actors who play an underreported role in the threat landscape.

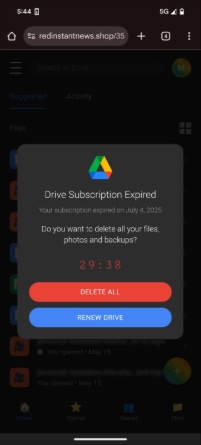

Parking threats are fueled by lookalike domains. No domain is immune. When one of our researchers tried to report a crime to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), they accidentally visited ic3[.]org instead of ic3[.]gov. Their phone was quickly redirected to a false “Drive Subscription Expired” page. They were lucky to receive a scam; based on what we’ve learnt, they could just as easily receive an information stealer or trojan malware. The real threat from parked domains comes from their ability to hide malicious activity. If we visit that same domain from a website scanner, it delivers a stereotypical parking page, leading people and automated systems to believe it is harmless. See Figure 1. See a recording of how the same domain delivers different threats here.

Figure 1. A scan of ic3[.]org, a lookalike to the FBI Internet Crime Complaint Center website, returned a non-threatening parking page (left) whereas a mobile user was instantly directed to deceptive content in October 2025 (right).

At the heart of the matter is a feature referred to as direct search or zero click parking, which is intended to directly deliver users relevant content based on the parked domain name. When a domain owner opts into direct search, traffic to the domain is sold to advertisers who bid on keywords and traffic characteristics. In practice, the site visitor is usually funneled through a series of traffic distribution systems (TDSs) operated by third-party advertising platforms, creating a complex web where a legitimate business model is weaponized for abuse.

The likelihood of encountering malicious content has risen dramatically since a major study was published over a decade ago. Those researchers, although alarmed by the potential risks, estimated that malicious content was delivered less than 5% of the time via parked domains. We’ve found that the situation is now reversed: malicious content is the norm. Aside from incidental typos, unscrupulous parties purchase formerly legitimate domains or lookalike domains and drive victims to them. Additionally, the rapid proliferation of generative AI tools plays a role in this threat landscape. AI chat systems incorporate internet history into their training models and can include outdated URLs in their answers. When these domains are picked up by bad actors, the seemingly trustworthy AI link can lead users to malicious content.

In large scale experiments, we found that over 90% of the time, visitors to a parked domain would be directed to illegal content, scams, scareware and anti-virus software subscriptions, or malware, as the “click” was sold from the parking company to advertisers, who often resold that traffic to yet another party. None of this displayed content was related to the domain name we visited.

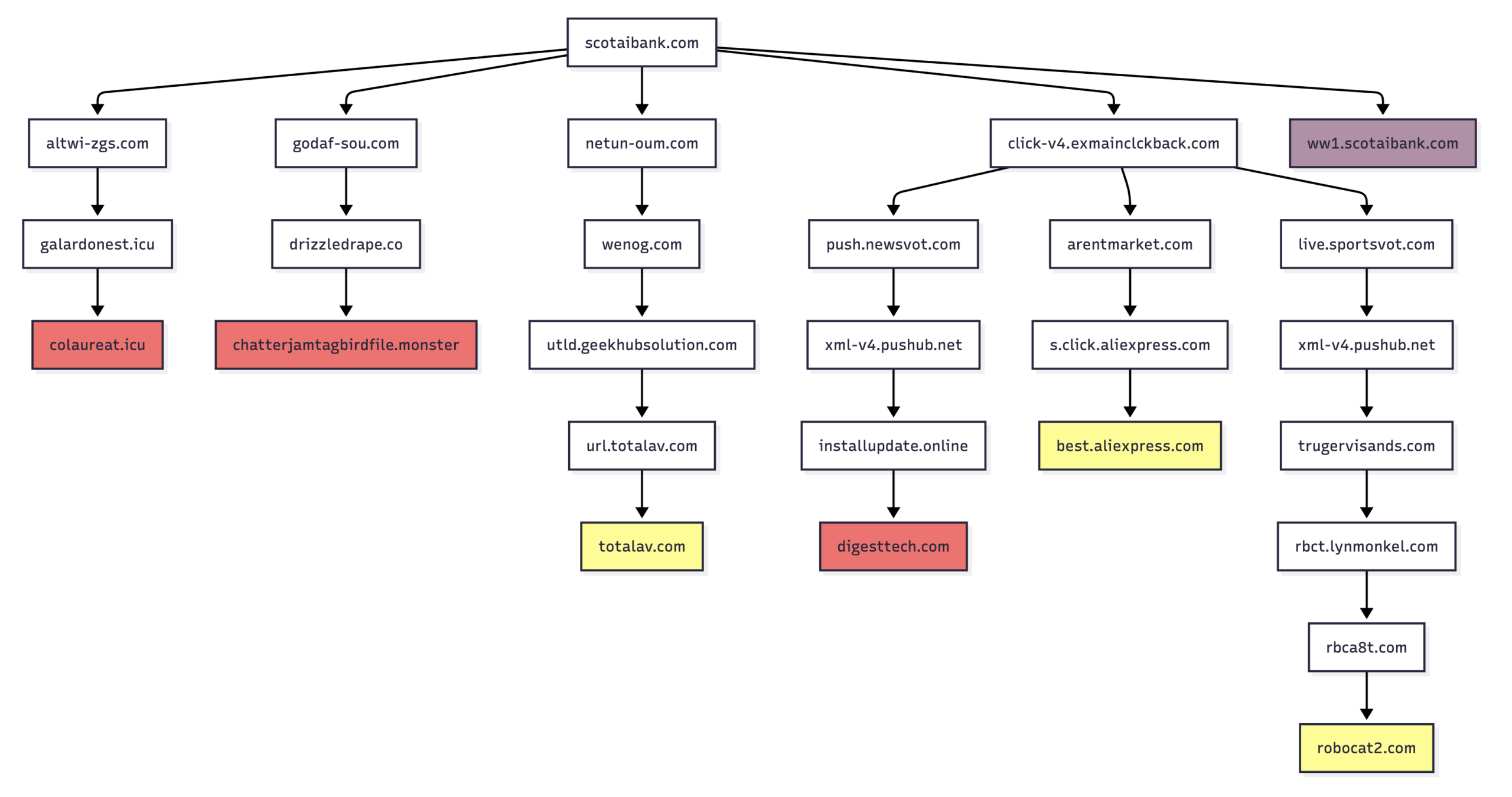

The details of the parking threat ecosystem are complex, so to illustrate the risks we will primarily examine a single domain: scotaibank[.]com, a typosquat of the legitimate domain for Canadian financial institution Scotiabank, scotiabank[.]com. Through this example, we’ll demonstrate how accidental typos, or lookalike domains, deliberately placed by cybercriminals can lead to a variety of threats.

Scotaibank[.]com is part of a domain portfolio full of lookalikes to major brands, who own some of the most popular sites on the internet. These lookalike domains are not directly parked with a major company. Instead, an intermediary server operates as a simple TDS and will redirect to a standard parking page if the visitor is not from a residential IP address. Otherwise, the domain controller will redirect to one of a few parking companies where even more sophisticated user fingerprinting occurs before the landing page is displayed.

We studied parking platforms, domain portfolio owners, publishers, and advertising networks for their role in delivering malvertising to end users. Sketchy players, along with abused entities, exist in every part of the ecosystem. While the scam or malware comes from the advertiser, we found domain portfolio holders often engage in suspicious practices and are an underreported element of the threat landscape. In this paper, we detail how:

- The scotaibank[.]com actor uses dedicated name servers and has a portfolio of nearly three thousand lookalike domains, including common typos like gmai[.]com. This Gmail lookalike is among many configured to receive mail and by all accounts it receives lots of it. We also found evidence that it is used deliberately in phishing and malware campaigns. The collection of personal information through mail is a risk associated with parked domains that goes beyond malvertising.

- Another actor—the one who holds ic3[.]org—rapidly rotates name servers and IP addresses for the parked domains in a “double fast flux” way. This sophisticated and rarely seen technique leverages dynamic DNS to avoid detection.

- A third actor owns domaincntrol[.]com, a domain that differs from GoDaddy’s name servers by a single character. They use this lookalike domain to take advantage of typos in innocent people’s DNS configurations, as well as to drive users to malware through their TDS. Recently, this actor altered their system to target Cloudflare Secure DNS (1.1.1.1) users specifically.

- These three domain portfolio holders target different demographics with a large collection of lookalike domains.

Many thanks to SURBL for their collaboration in this research. One of the earliest threats we investigated together were domains that were clever lookalikes to major corporations leading through parking platforms and funky captchas to advertisements for a variety of “privacy” applications. We were able to repeatedly go from a collection of parked domains to the same landing pages. Alarmed, we began to reach out to the parking platforms. Nearly a year later, Trinity Cyber released research demonstrating that these applications are powerful spyware.

During the past year, we contacted multiple companies in the parking industry to discuss the malvertising we observed through their platforms. Each firm recognized that both domain holders and advertisers could abuse the parking platforms. Even with a desire to help reduce abuse, direct search creates a paradox. The threats are downstream, and since the redirection chains leading to threats can pass through multiple advertising networks, “Know Your Customer” (KYC) doesn’t extend to these final destinations. Team Internet AG was particularly helpful to us during this investigation.

The malicious activity described in this report is not attributed to any known party. The parking or advertising platforms named in this report were not implicated in the malvertising we observed.

Direct Search Parking

Domains without a current webpage can be monetized by hosting them at a domain parking company that displays ads to visitors, generating passive income for the domain owner. Individuals who invested in domain names for future resale hope to make enough by parking them to pay for their annual domain renewals, and ideally a little extra for themselves. Some investors have large collections of domains; they are called “domainers” in the industry.

Traditional parking sites show advertisements that the website visitor must click on for the domain holder to be paid. But an alternative “zero click” model, referred to as direct search, has been available for years. Advertisers bid on traffic based on a variety of criteria, including keywords, location, and device information. The user will then be redirected to the winning bidder, which might be an advertising network. Trillion Direct explains it this way:

“Direct navigation search occurs when a user types a keyword-filled domain name into their browser’s address bar. These are high-intent search users who are bypassing search engines because they know exactly what they want, and they want it now.”

In practice, we found this isn’t true: rarely was the displayed content related to the parked domain name. The advertisements might have been related to the domain keywords a decade ago, but today that simply isn’t the case.

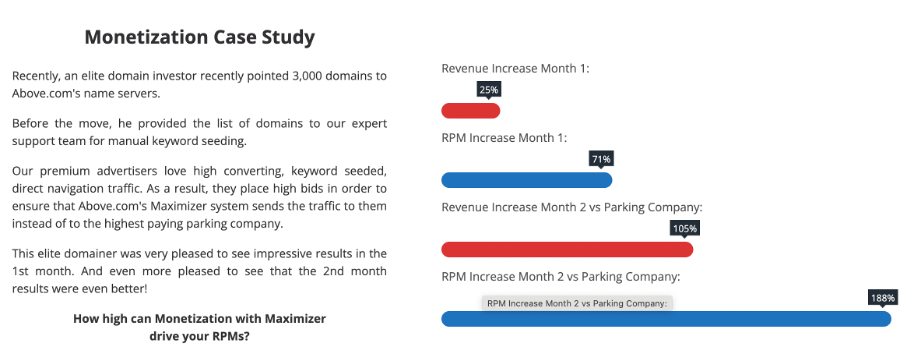

Whatever is advertised, high value domain portfolios can profit tremendously. According to Above.com, domainers might see an 188% increase in revenue within a few months; see Figure 2.

Figure 2. A monetization case study from Above.com demonstrates that domain portfolio owners can benefit greatly from using direct search.

While Above.com emphasizes “premium advertisers,” in practice we found that the traffic was frequently sold to affiliate advertising networks, who often sold the traffic again, meaning that the final advertiser had no business relationship with Above. This disconnect between the parked domain and the advertisement isn’t unique to Above; it was seen in every parking platform we examined.

Recent policy changes by Google may inadvertently increase the risk to users from direct search abuse. Google is the largest traffic buyer in the advertising industry. To combat fraud from parked domains, in March 2025, they began requiring advertisers to deliberately “opt-in” to parking traffic. Domain investors immediately saw a dramatic reduction in their income. In response, parking platforms like Above recommended that their clients adopt direct search to maintain a stable income from parked domains. Unfortunately, a greater adoption of direct search as it is today may help domainers but increase the risk for internet users and enterprises.

While threats are delivered by advertisers, domainers can profit enormously from direct search and also play a part in the threat landscape. Researchers in 2014 demonstrated that they could control the flow of traffic from parked domains to advertisements. During our investigation, we identified domainers who appeared to do exactly that. Team Internet referred to this scheme as “whitewashing” and it is similar to practices associated with master134. We found multiple large domainers, including the one who holds scotaibank[.]com, who actively participated in screening website visits. Some affiliate advertising networks, like RichAds, claim to own portfolios of parked domains and sell traffic from them to their customers.

Scotaibank[.]com Visitor Profiling

Scotaibank[.]com provides a good demonstration of the many ways that direct search is risky for internet users. We visited this domain hundreds of times and recorded the results. Figure 3 shows some of the redirection paths we observed while simulating different devices and browsers from different locations. The red boxes are domains connected to malware, scams, and deceptive content; the yellow to landing pages irrelevant to the initial domain such as gambling or antivirus; and the purple to the parking page that is essentially a decoy site. This figure reveals the complexity of traffic distribution for parked domains as well as the high level of risk for visitors.

Figure 3: Samples of redirection paths when visiting scotaibank[.]com. Each branch includes a series of domains observed, including the color-coded landing page.

A visit to scotaibank[.]com starts with lightweight fingerprinting. Based on the IP geolocation and user agent (UA) information, the site will either redirect to a stereotypical parking page or into a third-party advertising system. Connecting to the domain from a commercial VPN will display a standard parking page, but visiting from a residential IP address will lead into one of a handful of direct search platforms. In detail, when a user visits scotaibank[.]com:

- A DNS query is initiated for the A record of scotaibank[.]com.

- The name server, in this case ns1/ns2[.]torresdns[.]com, responds with an IP address.

- The visitor performs a GET request to the IP, which will include certain details such as the user agent string and requestor’s IP address.

- Software at the IP address fingerprints the user device and operates as a simple TDS:

- If it recognizes the IP as belonging to a cloud service or a commercial VPN, it will redirect the traffic to ww1[.]scotaibank[.]com. ‘ww1’ has a CNAME configured in DNS to resolve 9145[.]searchmagnified[.]com, which leads to a park page operated by the company Skenzo.

- If it recognizes the IP as a residential IP (and likely a human), it will provide a 302 redirect to send the traffic onward into another TDS.

In over 1000 scans from residential proxies and Tor, we were never sent to a standard parking page, and we never received content related to banking. Instead, our traffic was sold through advertising networks, sometimes several times, before an “advertisement” was displayed. Approximately 90% of the time we were directed to scams, malware, or unwanted content, but this content never came from a direct advertising partner of the major parking platforms, e.g., Zeropark and Trillion. Instead, it was delivered by downstream advertisers, making it impossible for them to know the identity of the malvertiser, and demonstrating the shortcomings of KYC mechanisms to address cybercrime in the case of direct search. The initial visit was funneled from the domain owner of scotaibank[.]com to one of four platforms: Zeropark, Trillion Direct Search, ExplorAds, and AdventureFeeds.

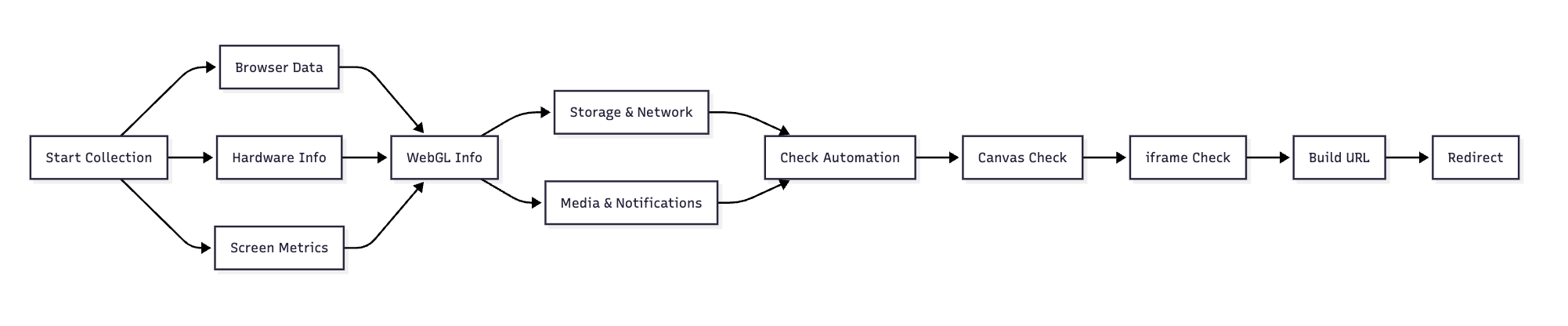

Each advertising platform performs fingerprinting and may resell the traffic again as a result. To demonstrate the depth of secondary profiling that these firms conduct, let’s consider a script used by one of the advertising affiliates of ExplorAds. It monitors iframes on the page, collects browser and hardware information, attempts to identify bots, and then sends a base64-encoded fingerprint to their TDS domain. See Figure 4. The data gathered includes:

- JavaScript and cookie support

- User-Agent, platform, and languages

- Screen dimensions, pixel ratio, and color depth

- WebGL vendor and renderer

- Audio and media capabilities

- Touch and pointer event support

- LocalStorage, SessionStorage, and IndexedDB availability

- Network information (downlink, RTT, and connection type)

- Notification API support

- Service worker and vibration support

Figure 4. Device fingerprinting by ExplorAds advertising affiliate, arentmarket[.]com, an unknown actor. This script contains comments in Russian.

Scotaibank[.]com Landing Pages

After profiling the user’s device, each TDS will redirect the user until they reach a final advertiser. Even then, in many cases, the user sees what advertisers call a pre-landing page, which funnels traffic even further. The click chain often also includes captchas, both real and fake, that limit access to the landing page and drive push notification subscriptions.

The landing pages we observed ranged from irrelevant to suspicious to outright malware. The legitimate sites appear to be decoys, served when some TDS in the redirect chain decided our traffic was bot-generated (in fairness, it was). Some of the landing pages we encountered were:

- Standard search parking page at Skenzo (seen for all VPN traffic)

- AliExpress, a popular online shopping website

- A page that automatically downloaded an installer for the web browser Opera GX

- Suspicious gambling sites

- Fake porn and dating sites

- Scareware and anti-virus subscription pages

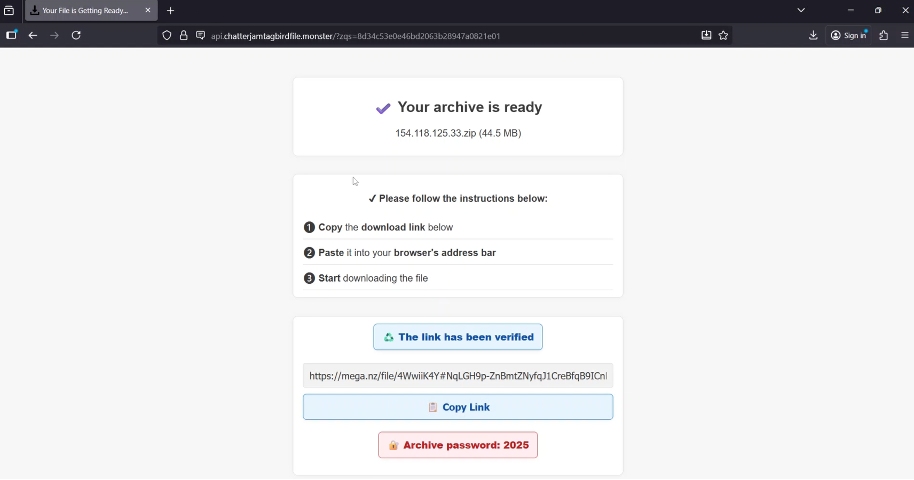

Occasionally, we were directed to malware. In one example, we were prompted to download an archive file containing a trojan. The lure was hosted at chatterjamtagbirdfile[.]monster. We were led to the payload from both ExplorAds and AdventureFeeds.

The chatterjamtagbirdfile[.]monster site said, “Your archive is ready” and gave us instructions to download the file and provided a password for the archive (Figure 5). Clicking the button showed a link to mega[.]nz, a popular file sharing website where the malware was hosted.

Figure 5: chatterjamtagbirdfile[.]monster page leading to Tedy malware

The ZIP file was not actually password protected. When we extracted it, it contained another archive inside: a .7z file named SourceOpen v.2.4.7z. This archive contained multiple files, a .DLL and an .EXE. Several security vendors’ products detected this as Tedy malware.

Tedy isn’t the only malware being delivered via direct search from parked domains; it is simply the one we saw from this single lookalike domain. We also encountered ClickFix attacks delivering Babar malware, information stealers, and spyware.

Scotaibank & Gmai: Held by the Same Lookalike Domainer

Malicious advertisers are one component of the risks associated with visiting parked domains, but they would not receive any traffic without domainers—those who hold investment portfolios of domains that drive traffic through the networks. Domainers often hold large numbers of lookalike domains, particularly ones that are common typos of major brands. Some have tens—or even hundreds—of thousands of domains. Domain monetization is big business for those who invest wisely.

Our research discovered several large domainers, including the owner of scotaibank[.]com, who appear to be directly involved in user profiling and not directly parking their domains at commercial platforms. These actors use IP geolocation, device fingerprinting, and cookies to determine where to redirect domain visitors. We analyzed their domain portfolios, DNS behavior, and redirection patterns.

The name servers of scotaibank[.]com are subdomains of torresdns[.]com and served nearly three thousand lookalike domains in 2025. While the identity of the domain holder is unknown, we associate the scotaibank[.]com holder with the torresdns[.]com owner based on consistent naming and behavior patterns. The torresdns domain was registered in 2016 but only appears as an authoritative name server starting in late-2019.

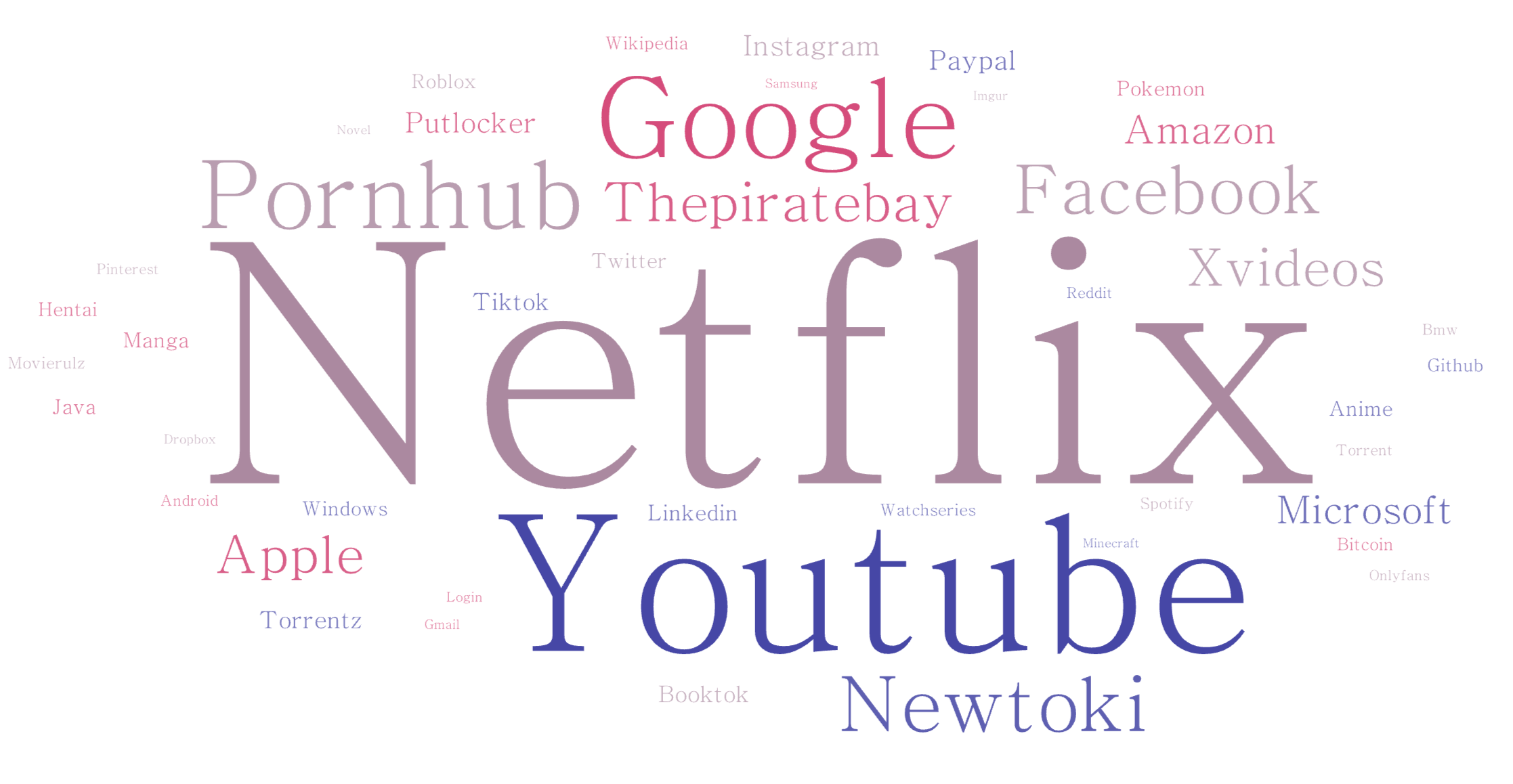

So, what other domains are part of the torresdns portfolio? We ran a proprietary lookalike detection algorithm on the domain names and uncovered a high density of typosquats of websites that the average person would visit: Craigslist, YouTube, Google, Wikipedia, and Netflix, to name the most common ones. Craigslist was the most prevalent, with 89 lookalikes. See Figure 6 for a depiction of the top 50 imitated brands.

Figure 6: Visualization of lookalike targets using torresdns[.] name servers, based on prevalence in the dataset.

Torresdns is not a simple domain investor: they actively evaluate visitors to the domains to determine where to forward the traffic. Referring to the sample click chains in Figure 3, security vendors, scanners, and bot traffic are consistently directed from the initial IP address to a traditional parking page hosted by Skenzo. Real users are instead sent into direct search parking systems through HTTP redirect.

Parked domains can be used for other malfeasances as well. The actor also holds gmai[.]com, a lookalike to Gmail and a common typo. This domain is configured with MX records. Email that is accidentally sent to the domain will be delivered to mail.h-email[.]net, which was registered in May 2023 and has no known associations to legitimate mail services. There are numerous reports of users accidentally sending personal information to a gmai[.]com account.

We also found a significant amount of suspicious and malicious spam in our collections that used the domain. Our investigation into this domain determined that gmai[.]com is not just used for passive email collection but has been actively leveraged in multiple business email compromise campaigns. One campaign we identified was actively operating as of November 2025, using a lure indicating a failed payment with trojan malware attached.

Details of an example email:

| Send Date | 2025/11/25 |

| Sender Email | sales@gmai[.]com |

| Email Subject | FWD: OUTSTANDING INVOICE PAYMENT. |

| Attachment Name | Bank Swiftcopy.rar |

| Attachment SHA256 | c3f1f456419f39f19c9e0d5aae2b50f701abe517a3cc2952869e516b260dbf88 |

The hundreds of thousands of spam emails collected and high volume of DNS resolutions we’ve identified related to gmai[.]com indicates a significant operation at play here, with the domain’s parked appearance being only the tip of the iceberg.

Double Fast Flux in Action

Another domain portfolio actor is rapidly changing both the authoritative name servers and IP addresses for domains in their parking inventory; a mechanism similar to “double” fast flux. Fast flux is the use of dynamic DNS capabilities to update records quickly, making them more difficult to track. This technique dates back two decades but gained renewed attention with a CISA advisory in 2025. The use of name server fluxing is, in our experience, rare and it is what distinguishes “double” fast flux from the more common practice which changes only A records. It is a mystery why the actor is using such a sophisticated and unusual technique, but they have around 80,000 domains in their portfolio, including some very clever lookalikes.

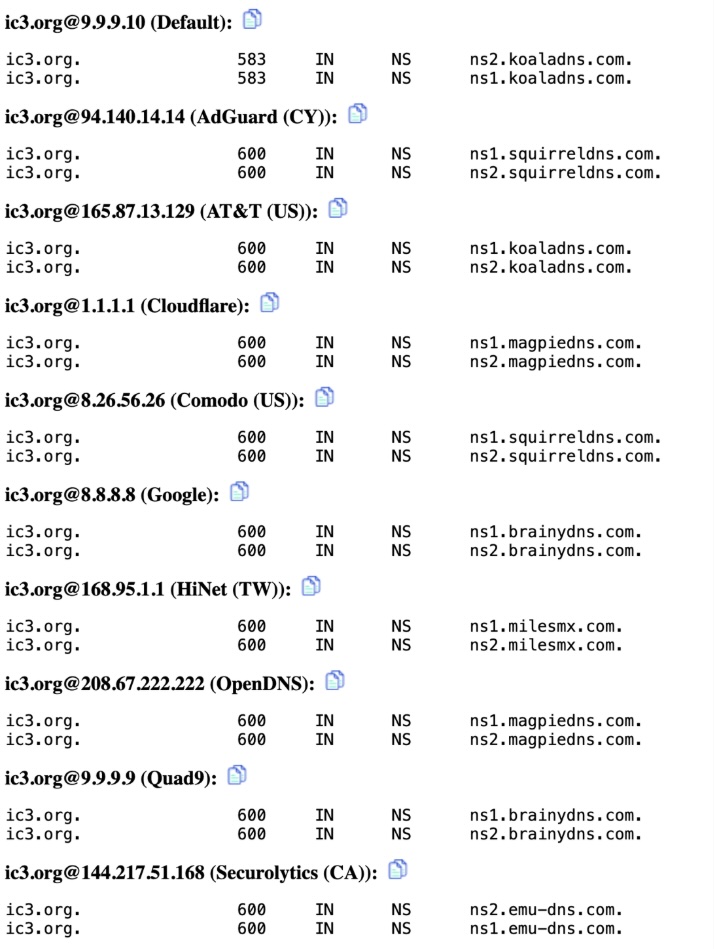

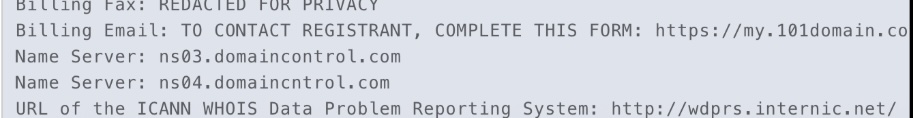

One domain in this actor’s portfolio is ic3[.]org, which has resolved to over 400 IP addresses since 2018. Queries for the name servers will rotate through a variety of different responses. See Figure 7 for various responses seen through different public resolvers using digwebinterface[.]com: the actor likes animals, it seems!

Figure 7: Image of name server results for ic3[.]org using digwebinterface[.]com on November 26, 2025. Name servers for ic3[.]org will have different results depending on which resolver is queried.

This operation seems to be designed for DNS lovers. The authoritative name server for ic3[.]gov was configured to brainydns[.]com in the .org zone file; however, when queried, brainydns[.]com often delegated to one of the above DNS servers. These name server records have a 600 second TTL, meaning different DNS resolvers will cache different name server responses, creating significant resilience against some blocking strategies.

The name servers we have seen used by this portfolio actor are:

- koaladns[.]com

- weaponizedcow[.]com

- numbatdns[.]com

- quokkadns[.]com

- emu-dns[.]com

- echidns[.]com

- magpiedns[.]com

- kirklanddc[.]com

- hastydns[.]com

- milesmx[.]com

In addition to name server tricks, this portfolio actor also funnels visitor traffic themselves before sending it to parking platforms. We found these domains to be resistant to security scanners. When the actor detects a VPN or bot, it will redirect them to a plain parking page at Skenzo. But when it perceives a real user, it sells the traffic to one of a handful of advertisers who perform further user profiling. The actor occasionally redirects to a major platform like Zeropark, but more often directs to a variety of less common advertising TDS domains including:

This fast flux actor also owns a large collection of typosquat domains. While the torresdns actor primarily targets well-known brands, this domainer holds many domain names that mimic adult content, gaming sites, and illegal activity, possibly targeting a younger audience. The most popular targets were Netflix, Youtube, Google, Pornhub, and Newtoki, which is a platform for unauthorized distribution of manga and comics. See Figure 8 for brands targeted by this actor.

Figure 8: A visualization of popular targets of domains that use koaladns[.]com as a name server.

The use of double fast flux, combined with the use of cloaking infrastructure to direct traffic from clever parked lookalike domains, indicates a professionally operated evasion system and a resilience not seen with typical typosquatting operations.

Usurping GoDaddy Name Servers

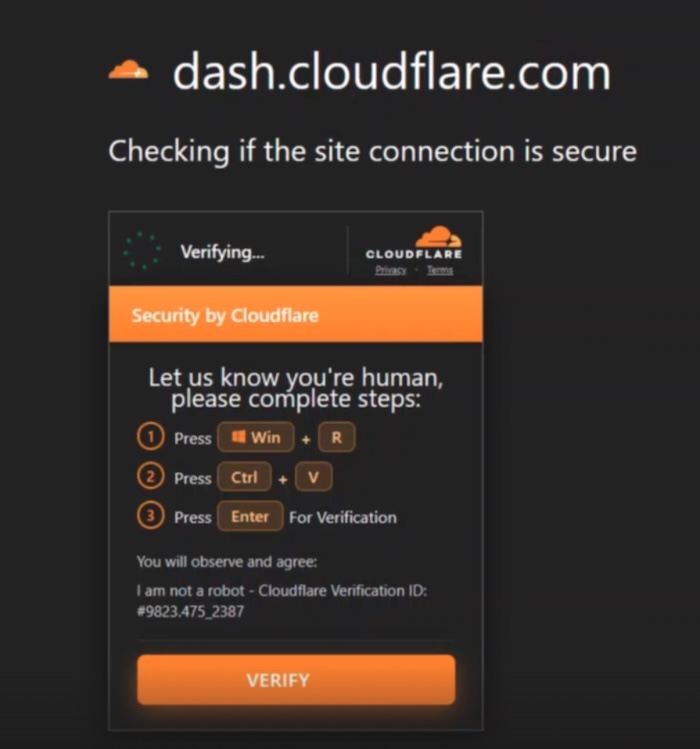

A third domainer not only leverages a large portfolio of domains but benefits from innocent parties who make a typo in their DNS name server records. The actor owns domaincntrol[.]com, which differs by a single letter from the GoDaddy name server domain, domaincontrol[.]com. The base typosquat domain, domaincntrol[.]com, displays a non-descript page containing only the phrase “We are a domain parking company…” They are a lot more than a parking company… and as of a few months ago, they began specifically targeting Cloudflare DNS (1.1.1.1) users.

Multiple methods drive traffic to their TDS. They appear to purchase expired domains, which may have lingering references on the internet from cached search results and outdated hyperlinks. Expired domains dropped through mergers and acquisitions, or rebranding, are particularly vulnerable. When a user visits one of the old links, they are sent into the actor’s TDS. In one example, the University Accounting Service (UAS) payment system migrated from uasecho[.]com to usaconnect[.]com in 2022, but when UAS let the original domain lapse, the domaincntrol actor took it over. As a result, users visiting the old payment portal were redirected to malicious content.

Another risk related to lingering URLs is Generative AI, which consumes them in the form of training data. The Japanese firm Kinto Technologies documented a specific case where an AI chat response led to a tech support scam through domaincntrol[.]com. In addition to the parked domain, Kinto found that over 20,000 websites contained code that redirected to domaincntrol[.]com in May 2025; we found nearly 30,000 sites in November.

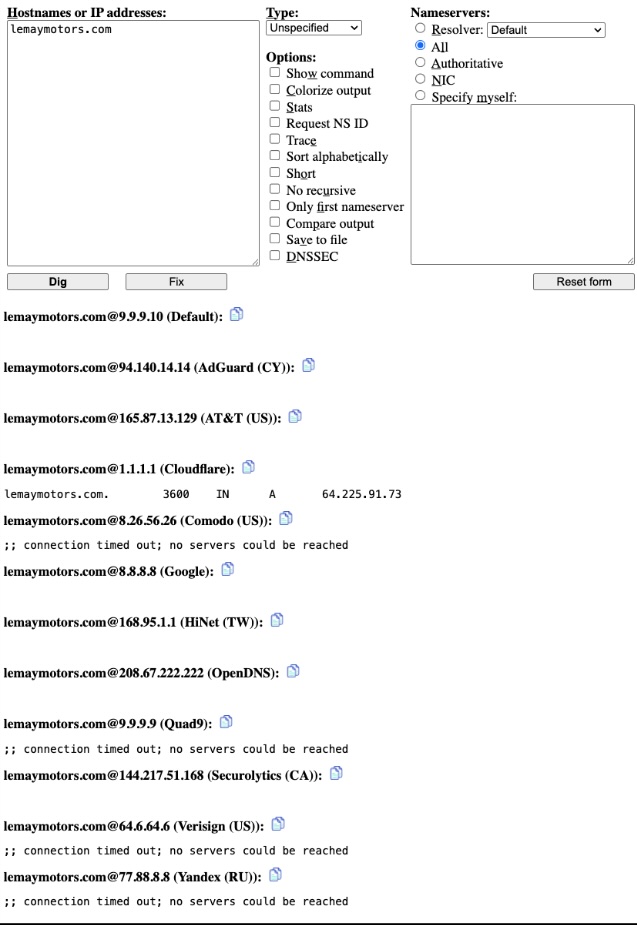

The actor also gains traffic from typos in DNS name server records. GoDaddy is the single largest registrar in the world and one of the largest hosting providers. It is not uncommon for innocent domain holders to make a typo when configuring their DNS records, enabling the parking actor to receive traffic intended for their site. Our research found that over 19k domains were configured to use domaincntrol[.]com as a name server, many owned by the domain actor, but others clearly misconfigured.

We found examples where only one name server record contained the single-letter typo. For example, in late November, the domain referenced in Figure 9 was configured this way. As a result, about 50% of their DNS traffic could go to GoDaddy and the rest to the typosquat-version TDS. Imagine what you can do with 50% of the traffic from random websites around the world.

Figure 9: Domain’s namevservers for gambel[.]law configured to both domaincontrol[.]com and domaincntrol[.]com in November 2025. A recursive resolver will pick from these two options.

When a user visits one of more than 30k domains that utilize the name server, they are first sent to 64.225.91[.]73 (Digital Ocean). A script there will attempt three times to run a javascript-based profiler at domaincntrol[.]com and otherwise do a force redirect to nojs[.]domaincntrol[.]com. The initial device fingerprinting is sent in HTTP headers as shown in Figure 10. From there, the user is either sent to parking at a major service, e.g., Sedo, Team Internet, or Skenzo, or their traffic is sold to a third-party advertiser.

Figure 10. An example of HTTP headers sent to domaincntrol[.]com for use in device fingerprinting.

The actor made a surprising change to their name server behavior in late July or early August 2025. Only queries from the Cloudflare 1.1.1.1 resolvers are answered; all other resolvers will receive an error or no response. See Figure 11. As a result, only users of Cloudflare’s secure DNS service are targeted. While this may seem limiting, 1.1.1.1 serves approximately 2 trillion DNS queries every day and is the default DNS resolver for Firefox users.

Figure 11. The name server domaincntrol[.]com selectively answers queries and directly answers Cloudflare 1.1.1.1 according to digwebinterface[.]com on November 25, 2025. Cloudflare users are sent to the IP address 64[.]225[.]91[.]73, which redirects to the actor’s TDS.

Using Cloudflare DNS, we visited lemaymotors[.]com and were immediately driven to a ClickFix attack delivering malware at sportswear[.]homes. See Figure 12. The page attempts to trick users into running a malicious script that downloads and executes a file (SHA256: 4a3497d66a64c22342d855d2da370c9a4351e6403bbd224093c4b348bd611df4) hosted at hxxp://85[.]209[.]129[.]9:5509/xa.vbs. Many security vendors’ products detected this as Babar malware.

Figure 12: ClickFix attack hosted on sportswear[.]homes.

It is unclear why the actor changed their system to target Cloudflare users recently, but selective resolution combined with the size of their domain portfolio and their ability to take advantage of mistakes in innocent domain holders’ DNS configurations makes them a formidable threat.

Conclusion

Parked domains may seem innocuous, but they are a bigger threat than most people think. Our research found that while unscrupulous advertisers were responsible for delivering malicious content, there are also large domain investment portfolio owners who are actively profiling devices and selectively driving internet users into dangerous territory. Their role in the parking threat landscape is underreported. At the same time, there is no clear path to effectively report abuse in the parking ecosystem. Reputable parking platforms gather KYC information on their direct customers, but the threat to internet users and enterprises is generally out of their purview. Moreover, the anti-fraud mechanisms these companies use inadvertently protect the bad advertisers from detection as well. Finally, an unintended consequence of Google’s advertising policy changes may be to exacerbate the threat by causing domain holders to increasingly adopt direct search. The number of malicious advertisers may not be high, but the risk that the average user reaches them through a simple typo sure is.

Indicators

Those indicators can also be found in our open GitHub repository.

| Indicator | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 86586f6954da38e5a5df7e56334ef98e74838dee68de0355ae4fe03d36c82502 4a3497d66a64c22342d855d2da370c9a4351e6403bbd224093c4b348bd611df4 c3f1f456419f39f19c9e0d5aae2b50f701abe517a3cc2952869e516b260dbf88 |

sha256 | Malware file |

| chatterjamtagbirdfile[.]monster colaureat[.]icu digesttech[.]com safezonefirewall[.]com sportswear[.]homes |

Domain | Landing page |

| velixnero[.]co[.]in drizzledrape[.]co installupdate[.]online |

Domain | Redirect domain |