This blog contains an excerpt of our new paper that unveils a previously unpublished multi-year operation using Domain Name System (DNS) queries, open DNS resolvers, and China’s Great Firewall. We detail what is known about the operation today and how to identify it in DNS logs. Further, we show that during these operations, the Great Firewall responds in a manner not previously documented, indicating that the threat actor is a Chinese nation state actor. This research highlights the ability and appetite of sophisticated actors to conduct extended operations undetected – analogous to the recent compromise of the open source xz library which filled the news cycle in March. Read the full research paper here.

This paper introduces a perplexing actor, Muddling Meerkat, who appears to be a People’s Republic of China (PRC) nation state actor. Muddling Meerkat conducts active operations through DNS by creating large volumes of widely distributed queries that are subsequently propagated through the internet using open DNS resolvers. Their operations intertwine with two topics tightly connected with China and Chinese actors: the Chinese Great Firewall (GFW) and Slow Drip, or random prefix, distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks. While Muddling Meerkat’s operations look at first glance like DNS DDoS attacks, it seems unlikely that denial of service is their goal, at least in the near term. Muddling Meerkat operations are long-running – apparently starting in October 2019 – and demonstrate a high degree of expertise in DNS.

Muddling Meerkat’s operations are complex. Indeed, they are so convoluted, one might assume that Muddling Meerkat presents no threat. But in cybersecurity, especially in the complex world of DNS, we should think strategically. In February 2024, the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and several international partners issued an advisory saying, “In recent years, the U.S. has seen a strategic shift in PRC cyber threat activity from a focus on espionage to pre-positioning for possible disruptive cyber attacks against U.S. critical infrastructure.”1 While that specific advisory focused on “living off the land” techniques used by the actor Volt Typhoon, the message that “PRC cyber actors blend in with normal system and network activities, avoid identification by network defenses, and limit the amount of activity that is captured in common logging configurations” is eerily similar to how well-hidden Muddling Meerkat remains.2

Muddling Meerkat’s operations are complex. Indeed, they are so convoluted, one might assume that Muddling Meerkat presents no threat. But in cybersecurity, especially in the complex world of DNS, we should think strategically. In February 2024, the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and several international partners issued an advisory saying, “In recent years, the U.S. has seen a strategic shift in PRC cyber threat activity from a focus on espionage to pre-positioning for possible disruptive cyber attacks against U.S. critical infrastructure.”1 While that specific advisory focused on “living off the land” techniques used by the actor Volt Typhoon, the message that “PRC cyber actors blend in with normal system and network activities, avoid identification by network defenses, and limit the amount of activity that is captured in common logging configurations” is eerily similar to how well-hidden Muddling Meerkat remains.2

Every detail of Muddling Meerkat operations demonstrates sophistication and deep knowledge of DNS The activity includes behavior not previously reported for the GFW, the nature of which ties the actor to Chinese nation state actors. While parts of their operations are similar to Slow Drip attacks, the motivation and goal of Muddling Meerkat are unclear. After analyzing the data, our major findings regarding Muddling Meerkat’s operations are that they:

- Use servers in Chinese IP space to conduct campaigns by making DNS queries for random subdomains to a wide array of IP addresses, including open resolvers

- Induce responses from the GFW that are not seen under normal circumstances

- Include false MX records from random Chinese IP addresses, a type of deception not previously reported for either the GFW or GC

- Trigger MX record queries, plus other record types, for short random hostnames of a set of domains outside the actor’s control in the .com and .org top-level domains (TLDs) from devices distributed worldwide (likely open resolvers)

- Use “super-aged” domains, typically registered before the year 2000, avoiding DNS blocklists and blending in with old malware at the same time

- Choose domains for abuse based on their length and age rather than their current status and ownership; while many of the domains are abandoned or have been repurposed for questionable use, other domains are actively used by legitimate entities

- Conduct campaigns of one to three days, similar to ExploderBot (see below), on a fairly continuous basis

- Do not appear to use large-scale spoofing of source IP addresses, but instead initiate DNS queries from dedicated servers

- Are limited in size to avoid detection and service disruptions like those caused by ExploderBot

- Are possibly conducted in discrete components, creating different DNS patterns over time

- Began on or about October 15, 20193

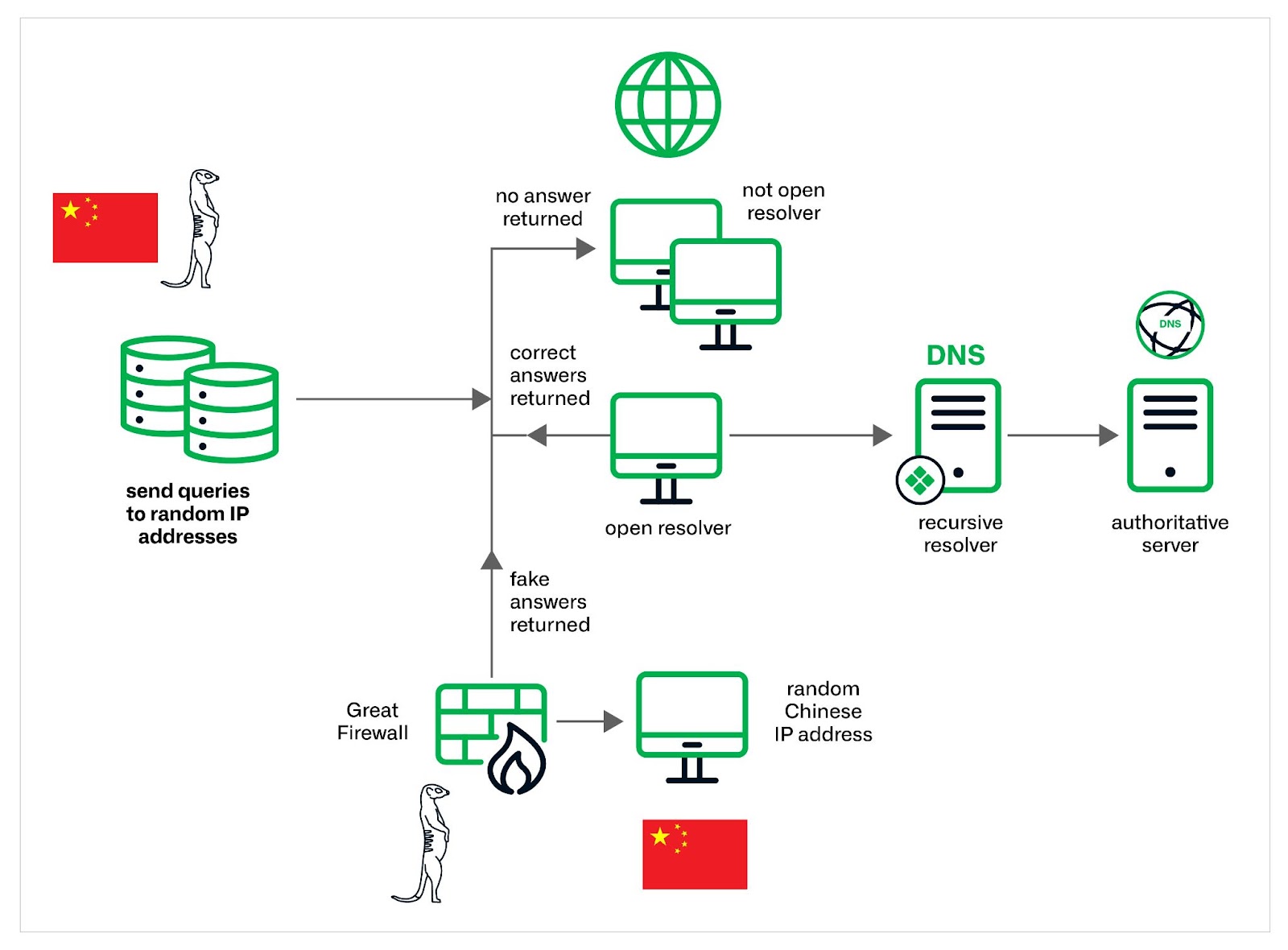

A simplified view of Muddling Meerkat’s operations as we understand them today is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. An overview of the Muddling Meerkat operations as currently understood. The Great Firewall is observed providing fake answers to MX queries, a behavior that has not been previously documented.

Our discovery of Muddling Meerkat was serendipitous, and the actor could have gone undetected for many more years if not for the data visibility of multiple organizations. This paper is joint research with undisclosed threat researchers and security vendors, as well as the Merit Network, an independent non-profit corporation governed by Michigan’s public universities, and DomainTools.4

I’ve taken the unusual step of writing this paper in first person. In part, first person seems more appropriate when telling a strange tale like this. In addition, my prior studies and publications about Chinese DNS threat actors have helped inform my conclusions about Muddling Meerkat. Earlier in my career, colleagues at the National Security Agency (NSA) and I spent thousands of hours studying a Chinese actor who performed DNS-based DDoS attacks over several years. We dubbed that actor ExploderBot and quietly published those findings in the spring of 2018. After operating nearly daily since 2014, wreaking havoc on internet service providers, ExploderBot ceased operations just over a month after our paper was released. They have not been seen since May 18, 2018. The nature of the Chinese DNS DDoS attacks changed, and I wrote a longitudinal study on the changes in late 2020. Since then, I haven’t spent much time looking at DNS DDoS attacks, Chinese or otherwise.

The GFW acts to prevent Chinese residents from accessing websites or services the government deems inappropriate or illegal5. But it is also known to inject false answers to DNS queries. The GFW applies to all IP traffic that crosses into, or out of, Chinese IP space. It is easy to demonstrate the GFW false answer behavior, which I show in the full paper. The GFW can be described as an “operator on the side,” meaning that it does not alter DNS responses directly but injects its own answers, entering into a race condition with any response from the original intended destination. When the GFW response is received by the requester first, it can poison their DNS cache. The GFW creates a lot of noise and misleading data that can hinder investigations into anomalous behavior in DNS. I have personally gone hunting down numerous trails only to conclude: oh, it’s just the GFW.

Muddling Meerkat came to my attention because inexplicable queries for mail server (MX) records were received at our recursive resolvers. In addition to the abuse of MX records, the queries had similar behavioral patterns, though at lower volumes, to DNS DDoS attacks. In a Slow Drip, or random prefix, DNS DDoS attack, queries for apparently random subdomains of a target domain are made on a large scale, typically propagated through open resolvers. These attacks originally emerged in 2014, and the first reported victims were Chinese. Several colleagues and I investigated DNS logs for multiple years of these attacks, concluding that most attacks that did demonstrable damage were conducted by a single actor, ExploderBot. ExploderBot used broadly distributed, spoofed IP addresses in their DNS queries, and the GFW responses served as red herrings hindering our analysis for a long time. When ExploderBot operations ceased in May 2018, what remained was a curious set of ongoing low-volume attacks with little apparent impact or purpose. In the past few years, random prefix attacks have impacted name servers somewhat regularly, but I have not seen the same volume level associated with ExploderBot.6

In this excerpt, I describe Muddling Meerkat operations in the context of what I know about the GFW, explain how to detect their activity, and discuss some of the pitfalls of trying to analyze actors like Muddling Meerkat. In particular, I want to warn readers about the dangers of open resolvers and the use of unregistered search domains in DNS or Microsoft Active Directory, which can lead to both participation in DDoS attacks and leaking network information to adversaries. In the full paper, I provide a more comprehensive discussion of the research, including further explanation about the GFW, and even how the reader can interact with it.

Why “Muddling Meerkat?”

As for the name Muddling Meerkat: The meerkat is a member of the mongoose family. Deceptively cute in appearance, it is clever, industrious, and exceptionally ferocious for its small size. Muddling Meerkat is known to abuse MX DNS records and conduct operations that involve the Chinese Great Firewall, adding confusion and red herrings to foil analysis. Due to the broad use of open resolvers for the operation, the activity also “pops up and down” over time and location, as meerkats do from their burrows.

MX Records for a Target Domain

The most remarkable feature of Muddling Meerkat is the presence of false MX record responses from Chinese IP addresses. This behavior, never published before, differs from the standard behavior of the GFW. These resolutions are sourced from Chinese IP addresses that do not host DNS services and contain false answers, consistent with the GFW. However, unlike the known behavior of the GFW, Muddling Meerkat MX responses include not IPv4 addresses but properly formatted MX resource records instead. This feature is truly remarkable and largely inexplicable.

I’ll use one of the many Muddling Meerkat target domains, kb[.]com., to demonstrate. The MX answer records for Muddling Meerkat are only observable in data collected outside of the normal DNS resolution chain because the source of the response is not a DNS resolver but instead a random Chinese IP address. Because Infoblox data is derived from our recursive resolvers, I partnered with other vendors to obtain data for analysis.

One third party provided DNS query-response data containing MX resource records for the domain kb[.]com over a period of 120 days ending in late January 2024. Specifically, each log included a DNS query for the MX record of kb[.]com and a response containing two resource records. The resource records were properly formatted, containing FQDNs with random hostnames of kb[.]com, typically three to six characters long. Examples of such MX record values include:

- pq5bo[.]kb[.]com

- uff0h[.]kb[.]com

- biuti[.]kb[.]com

- 8jxg1x[.]kb[.]com

- 8p0[.]kb[.]com

In the third-party data, properly formatted MX records are sourced from random Chinese IP addresses that do not host DNS servers. Moreover, these answers, while appearing correct at first glance, are false. The domain kb[.]com currently has authoritative name servers in China with NS1, an authoritative name service that is part of IBM. These authoritative name servers return no response to MX record queries for kb[.]com. Thus, we observed DNS responses coming from Chinese IP space that both differed from the normal GFW behavior and were false.

The third-party data contained not just a few MX records, but thousands. Every hostname within the historical MX record set was seen on a single day during this time frame for a total of over 8k unique FQDNs. The full paper has the details.

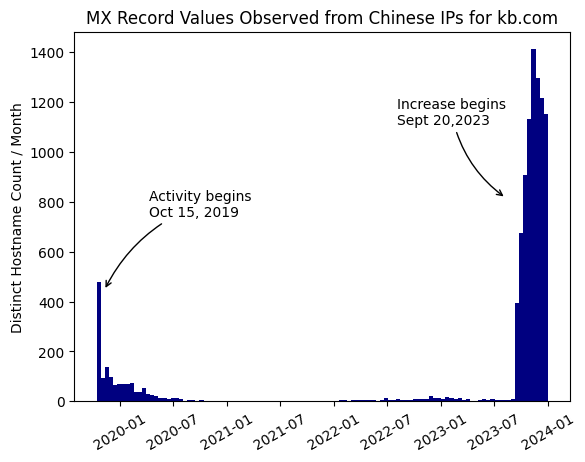

We also analyzed historical answers for MX records of kb[.]com over several years (Figure 2). MX records containing a random hostname were first observed on October 15, 2019. We have independently verified with other vendors that the first MX resolutions for Muddling Meerkat target domains were seen on, or about, October 15, 2019. This is true for all of the target domains we analyzed. Overall in third-party data, we see an inexplicable rise in the number of MX resolutions starting September 20, 2023, and continuing into early 2024.

Figure 2. Count of unique fake MX record values for kb[.]com, aggregated monthly over time and observed in third-party DNS data collections. The answerer IP addresses for these resolutions are random Chinese IP addresses which do not host DNS services, implying that the answer comes from the Great Firewall. These are all fake MX records that do not exist in the kb[.]com DNS zone file.

While the authoritative name servers for kb[.]com do not answer MX queries through the official DNS resolution process, our recursive resolvers do receive requests for these records. Under normal circumstances, receiving these requests would imply that users within our customer networks need to send email to a user at kb[.]com. But kb[.]com doesn’t serve mail. Passive DNS logs contain many strange things, and queries can be triggered by old applications or websites. However, in this case, the queries occur exactly one month apart over several months, lending to the intrigue.

MX Records for a Random Subdomain

The second identifying component of Muddling Meerkat operations also involves MX record queries—but for a random subdomain of the target domain, rather than the base domain itself. In this event, under normal circumstances, the query would be triggered by a user wanting to send email not to the base domain but to a subdomain. While this scenario does happen in normal DNS, it is not particularly common. In most of the Muddling Meerkat target domains, there is no functional mail server, creating an even more anomalous situation. Indeed, queries for MX records of random subdomains of kb[.]com are what led to this entire investigation.

The phenomena we observe at our recursive resolvers are a small number of MX record requests occurring over one to three days with random hostnames. These requests include other query types besides MX records, but because of the specific nature of MX records in normal network operations, I am only reporting findings on this type. The MX queries have this form:

where random is an alphanumeric string of variable length, typically between three and six characters long.

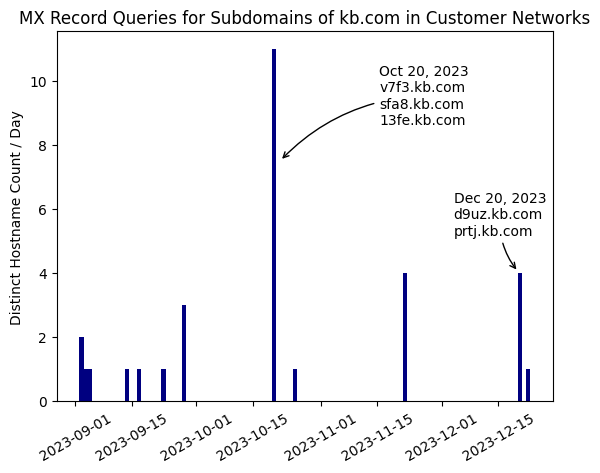

While this investigation began with kb[.]com, there are about 10 Muddling Meerkat target domains observed in our customer networks since September 1, 2023. Figure 3 shows the volume of MX queries for kb[.]com seen at our recursive resolvers between September 1 and December 31, along with some sample FQDNs queried on specific days. Over this four-month period, no subdomain is repeated. Our partners at DomainTools Farsight and other undisclosed vendors observe the same trends, albeit with different random subdomains. We provide further examples in the full research paper.

Figure 3. The number of distinct FQDNs with MX record queries for kb[.]com seen at Infoblox recursive resolvers during four months

Figure 3 demonstrates the aperiodic “pop up” nature of Muddling Meerkat queries with an operational tempo that lasts one to three days and uses random hostnames. This kind of pattern is typical of Slow Drip DDoS attacks in general and ExploderBot specifically. However, there are some significant differences between what was previously reported in the literature and these attacks. Most notably, in these attacks, the volumes are much lower than we would expect for a real attempt at a DDoS and those seen in large-scale attacks at the height of this activity between 2014 and 2017.

IPv4 Records for Random Subdomains

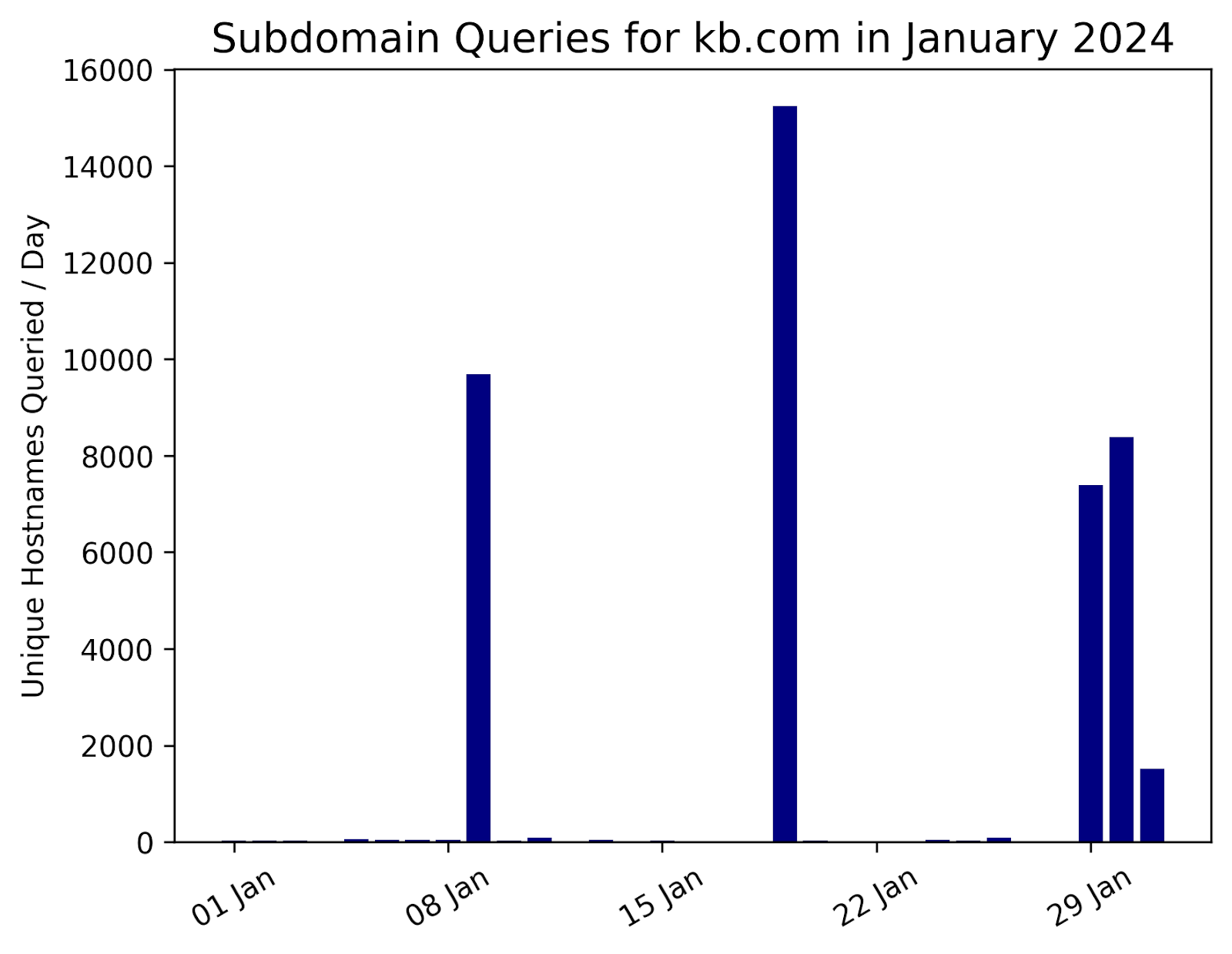

In addition to MX queries for random subdomains of the target domain, our recursive resolvers receive requests for A records, or IPv4 addresses. Of course, these queries do not receive answers from our resolvers because there is no such subdomain configured at the authoritative name server. Other vendors whose collection comes from recursive resolvers have similar observations. DomainTools Farsight data, for example, comes from a collection of recursive resolvers globally. Like Infoblox, those vendors see regular spikes in queries for random subdomains of the Muddling Meerkat domains, including A record queries. Figure 4 shows these trends for one month, January 2024.

Figure 4. Unique hostname queries of kb[.]com observed in Farsight pDNS in January 2024

There are also other types of collection with visibility into DNS, including packet collection, honeypots, and internet telescopes. Working on the theory that the source of these queries within our networks was open resolvers, and that Muddling Meerkat likely was probing a broad spectrum of IPv4 space for open resolvers, I asked other vendors to help locate packets that contained resource records in the response. We found A record responses, just as we found MX record responses.

The only IP addresses that “answered” queries for A records of Muddling Meerkat domains were in Chinese IP space. These IP addresses were not open on port 53, meaning they were not DNS resolvers. In other words, these answers came from the GFW and not the authoritative servers.

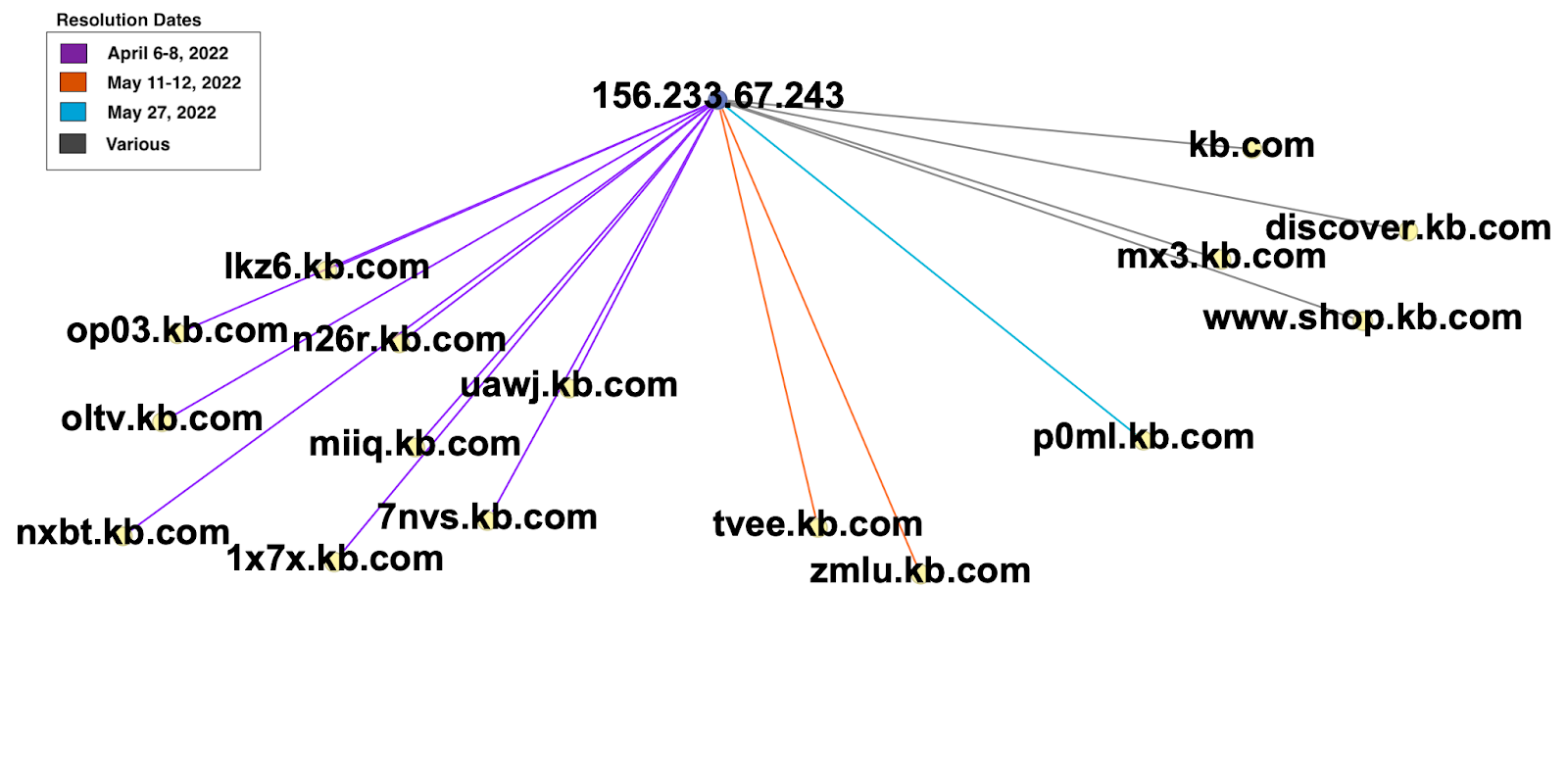

Using IP resolutions of subdomains of kb[.]com, we mapped the occurrence of a forged resolution IP address with the timeline of queries. In every case, the resolution IP address is seen repeatedly, with distinct time windows lasting one to three days, for short random subdomains. Figures 5 and 6 show two examples of this behavior. The two IP addresses are not related to kb[.]com; these are fake answers from the GFW. Both IP addresses are seen on overlapping days. Each figure shows the entirety of resolutions for kb[.]com subdomains to that IP address in 2022. As with the Infoblox and Farsight resolver data, the hostname, or subdomain, is not repeated.

Figure 5. Hostname resolutions by the GFW within the kb[.]com domain to the IP address 156[.]233[.]67[.]243 during 2022. This IP address is not related to kb[.]com and the answer is forged by the GFW.

![Hostname resolutions by the GFW within the kb[.]com domain to the IP address 208[.]101[.]21[.]43 during 2022. This IP address is not related to kb[.]com and the answer is forged by the GFW](/wp-content/uploads/hostname-resolutions-by-the-gfw-within-the-kbcom-domain-to-the-ip-address-2081012143-during-2022-this-ip-address-is-not-related-to-kbcom-and-the-answer-is-forged-by-the-gfw.png)

Figure 6. Hostname resolutions by the GFW within the kb[.]com domain to the IP address 208[.]101[.]21[.]43 during 2022. This IP address is not related to kb[.]com and the answer is forged by the GFW.

These results indicate that Muddling Meerkat is conducting operations that include DNS queries to a large number of destination IP addresses, regardless of their location or open ports, and that the GFW is injecting responses to these domains on specific days with a set of IP addresses that are used over time.

Here is where things get interesting: The GFW doesn’t normally inject answers for kb[.]com. The GFW is not injecting fake responses to any random subdomain request of kb[.]com, only those created by Muddling Meerkat! As we discussed earlier, the GFW injects answers to popular domains or to domains that it finds somehow objectionable to Chinese interests. Figure 7 shows the response on January 13, 2024, to an A record query for nxbt.kb[.]com from the IP address 111[.]193[.]204[.]201 that we used earlier to get fake responses to google[.]com.

![Figure 7. The response to an A record request from 111[.]193[.]204[.]204 for nxbt[.]kb[.]com. This IP address is in Chinese IP address space and is not open on port 53. The answer is what is expected for a query of this type and is consistent with known behavior of the GFW. Image credit: diggui.com.](https://blogs.infoblox.com/wp-content/uploads/the-response-to-an-a-record-request-from-111193204204-for-nxbtkbcom-this-ip-address-is-in-chinese-ip-address-space-and-is-not-open-on-port.png)

Figure 7. The response to an A record request from 111[.]193[.]204[.]204 for nxbt[.]kb[.]com. This IP address is in Chinese IP address space and is not open on port 53. The answer is what is expected for a query of this type and is consistent with known behavior of the GFW. Image credit: diggui.com.

Open resolvers play an important role in Muddling Meerkat operations. Evidence suggests that the queries are sent to a wide range of IP addresses, many of them open resolvers, from Chinese IP space. The destination IP addresses for the DNS queries likely rotate over time, which creates a “pop up” signature at recursive resolvers like Infoblox. In other words, I suspect Muddling Meerkat is actively muddling with the internet more often than we observe at Infoblox cloud resolvers. Instead, I suspect at certain intervals, lasting a few days at a time, external IP addresses belonging to our customers are included in the Muddling Meerkat destinations. (This is speculation on my part; I don’t have data visibility to see the full scope of activities.) Some of our customers unwittingly have open resolvers in their network that receive their queries and forward them to our resolvers for resolution. Regardless of the operational tempo, we will only see Muddling Meerkat queries at our resolvers when a customer device forwards them.

The Role of Chinese IP Addresses

Because of the complexity involved in Muddling Meerkat operations, and the impact of the GFW, it is challenging to determine whether specific events with Chinese IP addresses are “real.” What I mean here by “real” is that it can be unclear whether a specific IP address is “answering” a query as a result of the GFW. Similarly, it can be difficult to separate spoofed IP addresses from those that originated queries.

Our approach to this problem was to draw conclusions from overall statistics. As explained in the previous section, IPv4 Records for Random Subdomains, we observed that Chinese IP addresses “answered” Muddling Meerkat queries where that IP address is known to not have port 53 open. With a large number of these types of examples, we can conclude that “answers” are results of the GFW and not “real” answers.

When we look at querier behavior, some IP addresses stand out. These IP addresses occur with a much higher frequency than the open resolver IPs. They are the source of queries that were outside of the normal resolution for DNS, including to IP addresses that were hosting open resolvers. Some of these querier IP addresses have been repeatedly reported for aggressive scanning and other questionable practices.7 It seems most likely that these IP addresses are controlled by the threat actor and used during the operation. Table 1 presents an example of source IP addresses and queries.

| Querier IP Address | Query Name |

|---|---|

| 183[.]136[.]225[.]45 | ybzz[.]kb[.]com, xv9k[.]kb[.]com, 0h5w[.]kb[.]com |

| 183[.]136[.]225[.]14 | y4fw[.]kb[.]com, mq5i[.]kb[.]com, h420[.]kb[.]com |

| Table 1. Sample querier IP addresses and queries observed in January 2024. These IP addresses were not hosting open resolvers as of January 31, 2024. Some of these queries were directed at known open resolvers. | |

Locating Muddling Meerkat Activity

Muddling Meerkat can be observed, in part, from several vantage points. Recursive resolvers, like ours, can observe both queries for random subdomains as well as queries for MX records of the target domains. When resolved through the global DNS, the vast majority of these queries will result in an NXDOMAIN response.

For those who can observe them, Muddling Meerkat queries are likely to appear intermittently, similar to the examples in Figures 3 and 4, and depend on the size of the network. At Infoblox, we see more Muddling Meerkat traffic than a typical organization would because we resolve DNS queries for customers around the world. Our cloud recursive resolvers handled over 7.3 trillion queries in 2023.

In addition to DNS query logs, researchers should be able to find traces of Muddling Meerkat in a number of other sources:

- The root, TLD, and authoritative name servers will all have evidence of Muddling Meerkat activity dating back to October 2019 and possibly earlier. Because the actor does not control the target domains, and they are querying broad IP ranges for the records, open resolvers will forward the queries and result in requests at each server within the resolution chain.

- Recursive resolver caches also capture evidence of Muddling Meerkat

- DNS honeypot owners will likely receive queries depending on how broadly Muddling Meerkat queries IP addresses.

- Flow data may contain indications of activity, particularly if it monitors Chinese IP space or shows an unusual variety of port 53 connections to the authoritative name servers, especially arising from open resolver IP addresses.

Queries to any domains provided at the end of this report should be considered suspect. But keep in mind the broad use of these domains for Active Directory and DNS search domains. In addition to the target domain, there should be MX record queries, particularly for short random subdomains. There are other suspect queries for a subset of the Muddling Meerkat domains, which are not included in this report. These are A record queries that appear to leak network information to the authoritative server. However, I am not able to definitively tie this activity to Muddling Meerkat.

Attribution and Motivation

Muddling Meerkat appears to be a Chinese state actor. Because we can observe MX record responses from Chinese IP addresses that are not open on port 53 of Muddling Meerkat target domains over multiple years, I am confident those responses are results of the GFW. At the same time, proper MX responses from the GFW have never been reported before and researchers, including myself, have been unable to trigger the behavior manually. In order to induce selective responses like those we have observed over four years, it seems that Muddling Meerkat must somehow be connected to the GFW operators. While I don’t know how these selective responses are triggered, it is possible that signatures contained in the IP packets, like those observed in ExploderBot traffic, are used to signal a different response from the GFW.

The motivation for these operations is unclear. The data we have suggests that the operations are performed in independent “stages;” some include MX queries for target domains, and others include a broader set of queries for random subdomains. The DNS event data containing MX records from the GFW often occurs on separate dates from those where we see MX queries at open resolvers. Because the domain names are the same across the stages and the queries are consistent across domain names, both over a multi-year period, these stages surely must be related, but we did not draw a conclusion about how they are related or why the actor would use such staged approaches.

Recommendations

Our research highlights potential network vulnerabilities that arise from neglect and the complexity of modern internet communications. In particular, I recommend that network administrators:

- Actively seek out and eliminate open resolvers in their networks. Identifying these devices can be challenging, but companies like Infoblox and organizations like the Shadow Server Foundation can offer critical information to help.

- Do not use domains that you do not own for Active Directory or DNS search domains. You are very likely to leak information about your network and user applications to the authoritative name server, as well to other appliances outside of your control. This kind of information can allow a bad actor to perform passive reconnaissance of the network for targeted attacks.

- Incorporate DNS detection and response (DNSDR) into your security stack. Only a DNS resolver can effectively handle threats that are inherently in DNS. Most security products won’t even recognize the difference between an MX query and an A record query.

- Report Muddling Meerkat activity to the community. Because it is impossible to observe the entire scope from any one vantage point, it is important to crowdsource an understanding of this threat. In particular, reporting additional Muddling Meerkat domains will help others find open resolvers and activity in their network.

Ultimately, I share the concerns expressed by CISA about the PRC and the threat of pre-positioning for cyberattacks globally. In my professional experience, I have found Chinese threat actors to be extremely adept at managing, understanding, and leveraging the DNS for many purposes—whether that be censorship, cybercrime, or DDoS attacks. They also have some of the finest researchers in the field. Whatever the real goal of Muddling Meerkat is, we should not underestimate the talent and patience required to achieve it.

Learn more about the Great Firewall and read the full research report here.

Indicators of Activity

Note that these domains are not indicators of compromise or necessarily malicious. Some of the domains used by Muddling Meerkat are parked, others host gambling sites and other possibly illegal content, and others are active legitimate domains. The full scope of Muddling Meerkat target domains is likely much larger.

These domains host no website, host illegal content, or are parked. They likely can be blocked without impact:4u[.]com, kb[.]com, oao[.]com, od[.]com, boxi[.]com, zc[.]com, s8[.]com, f4[.]com, b6[.]com, p3z[.]com, ob[.]com, eg[.]com, kok[.]com, gogo[.]com, aoa[.]com, gogo[.]com, zbo6[.]com, id[.]com, mv[.]com, nef[.]com, ntl[.]com, tv[.]com, 7ee[.]com, gb[.]com, tunk[.]org, q29[.]org

These domains host websites and blocking them may negatively affect your network:

ni[.]com, tt[.]com, pr[.]com, dec[.]com

IP addresses used to launch attacks:

- 183[.]136[.]225[.]45

- 183[.]136[.]225[.]14

Footnotes

- https://www.linkedin.com/posts/cisagov_with-us-and-international-government-partners-activity-7161082451354603520-pv0q

- https://www.cisa.gov/resources-tools/resources/identifying-and-mitigating-living-land-techniques

- There is some evidence that the operations began a few months early, in June 2019, but I am unable to validate this date.

- https://www.merit.edu/

- https://www.cybereason.com/blog/malcious-life-podcast-the-great-firewall-of-china-part-1

- https://infosec.exchange/@ricci@discuss.systems/111508151184559310

- https://www.abuseipdb.com/check/183.136.225.14?page=8