Consumers are increasingly concerned about privacy, especially with networks and websites collecting information about Internet browsing activities. There are two components to that privacy equation: who and what. Who relates to who I am, and what devices are I connecting to the Internet from; this can be my phone, laptop, smart TV, and game console. Just a quick scan of my router shows over 75 devices connected within my household. You can also expand on this to include where am I connecting from? For instance, my cable modem may be allocating the same IP address, and I’m connecting from the same zip code. But then there’s what: what websites am I accessing? What type of content am I spending most of my time on? When the “who” and the “what” are combined, companies can build (and continually enhance) their profile of me because this information helps identify who I am, where I am, and what sites I’m visiting (even if I am traveling).

iCloud Private Relay

For several years, Apple has positioned itself as a privacy-sensitive company. For example, recent versions of its operating systems gave users more control over which apps could collect and use personal data. Beginning with iOS 14 and macOS Big Sur, Apple added support for DNS over TLS (DoT) and DNS over HTTPS (DoH) to encrypt DNS communications between device stub resolvers and local applications and recursive DNS resolvers. While these communications are encrypted, the “who” and the “what” privacy component remains.

Enter iCloud Private Relay (while available, is still in beta), which behaves as a connector between your devices and the websites you visit, detaching these two pieces of information to help create a better level of privacy. Source IP addresses and websites (and thus, browsing activities) are separated between two relays. Private Relay is available to users who have optionally subscribed to iCloud+ and can be enabled per device.

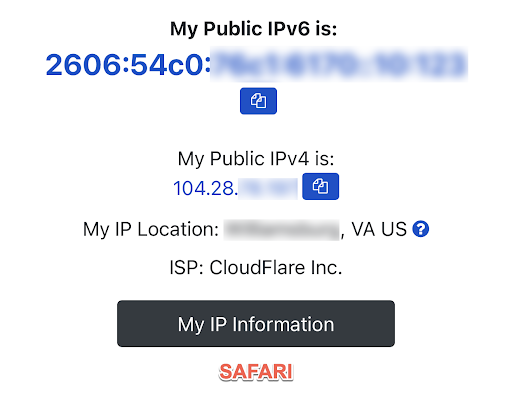

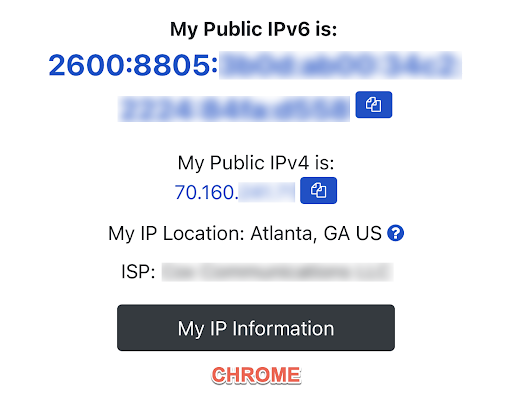

Once enabled and when users access the Internet through the Safari browser on compatible Apple devices, Private Relay operates similarly to a VPN by encrypting data transmitted to the first relay. Apple then strips away the original IP address attached to that information and forwards the request to a second relay. The second relay does not know the actual IP address that identifies the user, but they do know what website they are visiting. They add an anonymous IP address showing a general geographic location in your vicinity and send the information to the original website destination. One note: while Private Relay may look like a VPN on the surface, it’s not. For example, users cannot choose an IP address or even a region to make it look like they are located in a completely different country (a common tactic to bypass geo-locked content restrictions).

Figure 1: Private Relay enabled on my iPhone. Top (using Safari) reflects Private Relay IP address changes. ISP is reflected as CloudFlare. Bottom shows my original IP addresses and ISP through the Chrome browser.

Also, Private Relay works primarily with Safari (and potentially a handful of other apps that transmit data in cleartext) and not the vast majority of apps running on devices. That allows users to decide how to use the service; online banking while on the road? Safari might be the best app for that. Last, the feature is easily identifiable as a proxy server, allowing organizations like enterprises and schools to block private relay since they may be required by policy or law to monitor their network traffic.

Impacts to Carriers

It’s no surprise that carriers are not huge fans of Private Relay, and many of the largest European mobile operators have asked the European Commission to “stop Apple from using Private Relay on the grounds that it will also prevent them from managing their networks.” Many providers are also blocking access to Private Relay on their networks. Carriers use the information gained from DNS query data to help manage their networks and protect subscribers from harmful online material. For example, carriers can determine the geographically closest instance of websites that subscribers seek to deliver content faster. Through DNS content filtering, carriers can protect children in homes, schools and libraries from accessing harmful or objectionable content. Carriers also rely on DNS query data to comply with law enforcement requests for subscriber Internet activity records. In addition, DNS information can defend the network and subscribers from evolving cyber threats.

Conclusion

New technologies like Private Relay, besides DoT and DoH, provides users with another tool in their privacy toolbox–but also affects carriers, enterprises, and other network owners who often have corporate, legal, ethical, or other responsibilities to monitor, report, and control the behavior of the devices connected to their networks. While many don’t question the motives of improving user privacy, many carriers, enterprises and other organizations will want to maintain visibility and control over their network traffic. The last several years have introduced many changes to how DNS functions. The good news is that Infoblox can help you maneuver these changes and help you implement the best practices that make the most sense for your organization.